In early November 1927, the front pages of newspapers all over France featured photographs not of the usual politicians, aviators or sporting events, but of a group of archaeologists engaged in excavation. The slow, painstaking work of archaeology was rarely headline news. But this was no ordinary dig.

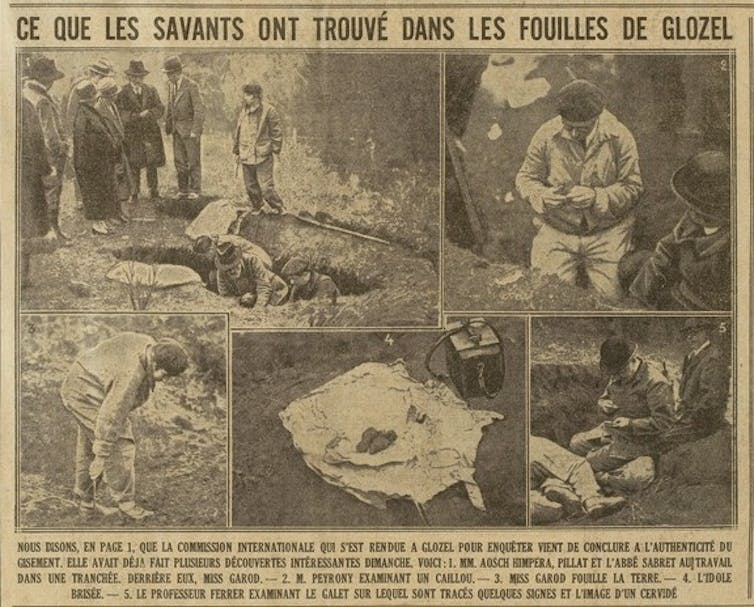

A front-page spread in the Excelsior newspaper from Nov. 8, 1927, features archaeologists at work in the field with the headline ‘What the learned commission found at the Glozel excavations.’

Excelsior/BnF Gallica

The archaeologists pictured were members of an international team assembled to assess the authenticity of a remarkable site in France’s Auvergne region.

Claude and Émile Fradin’s family first spotted the artifacts on their land.

Agence Meurisse

Three years before, farmers plowing their land at a place called Glozel had come across what seemed to be a prehistoric tomb. Excavations by Antonin Morlet, an amateur archaeologist from Vichy, the nearest town of any size, yielded all kinds of unexpected objects. Morlet began publishing the finds in late 1925, immediately producing lively debate and controversy.

Certain characteristics of the site placed it in the Neolithic era, approximately 10,000 B.C.E. But Morlet also unearthed artifact types thought to have been invented thousands of years later, notably pottery and, most surprisingly, tablets or bricks with what looked like alphabetic characters. Some scholars cried foul, including experts on the inscriptions of the Phoenicians, the people thought to have invented the Western alphabet no earlier than 2000 B.C.E.

Was Glozel a stunning find with the capacity to rewrite prehistory? Or was it an elaborate hoax? By late 1927, the dispute over Glozel’s authenticity had become so strident that an outside investigation seemed warranted.

The Glozel affair now amounts to little more than a footnote in the history of French archaeology. As a historian, I first came across descriptions of it in some histories of French archaeology. With a bit of investigating, it wasn’t hard to find first-person accounts of the affair.

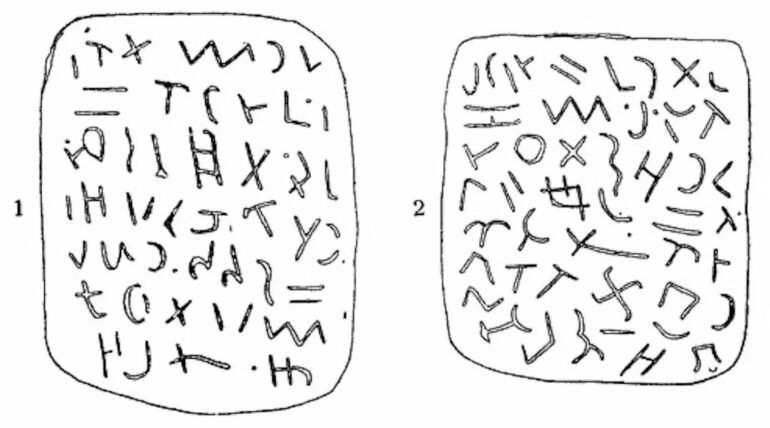

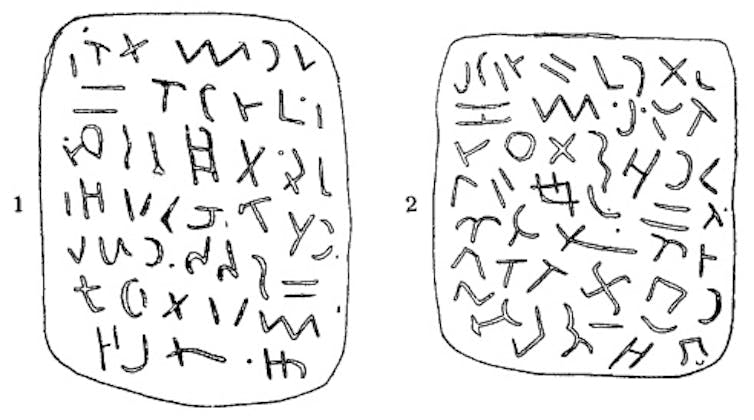

Examples of the kinds of inscriptions found at the Glozel site, as recorded by scholar Salomon Reinach.

‘Éphémérides de Glozel’/Wikimedia Commons

But it was only when I began studying the private papers of one of the leading contemporary skeptics of Glozel, an archaeologist and expert on Phoenician writing named René Dussaud, that I realized the magnitude and intensity of this controversy. After publishing a short book showing that the so-called Glozel alphabet was a mishmash of previously known early alphabetic writing, in October 1927 Dussaud took out a subscription to a clipping service to track mentions of the Glozel affair; in four months he received over 1,500 clippings, in 10 languages.

The Dussaud clippings became the basis for the…