King Solomon may have gained some of his famed wisdom from an unlikely source – ants.

According to a Jewish legend, Solomon conversed with a clever ant queen that confronted his pride, making quite an impression on the Israelite king. In the biblical book of Proverbs (6:6-8), Solomon shares this advice with his son: “Look to the ant, thou sluggard, consider her ways and be wise. Which having no guide, overseer, or ruler, provideth her meat in the summer, and gathereth her food in the harvest.”

While I can’t claim any familial connection to King Solomon, despite sharing his name, I’ve long admired the wisdom of ants and have spent over 20 years studying their ecology, evolution and behaviors. While the notion that ants may offer lessons for humans has certainly been around for a while, there may be new wisdom to gain from what scientists have learned about their biology.

Ants have evolved highly complex social organizations.

Lessons from ant agriculture

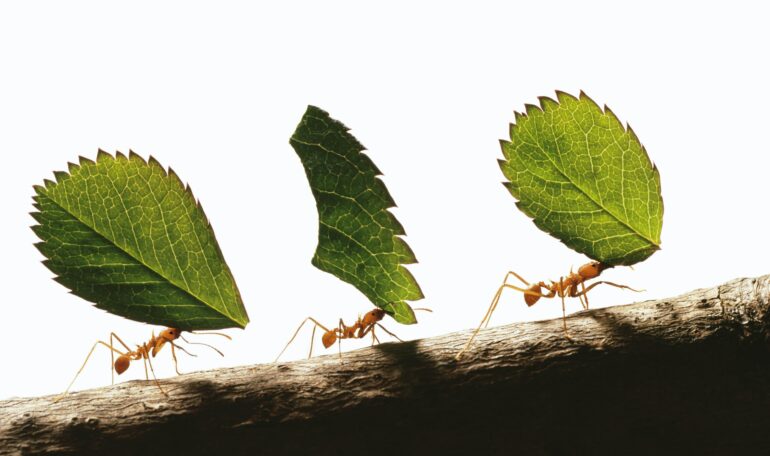

As a researcher, I’m especially intrigued by fungus-growing ants, a group of 248 species that cultivate fungi as their main source of food. They include 79 species of leafcutter ants, which grow their fungal gardens with freshly cut leaves they carry into their enormous underground nests. I’ve excavated hundreds of leafcutter ant nests from Texas to Argentina as part of the scientific effort to understand how these ants coevolved with their fungal crops.

Much like human farmers, each species of fungus-growing ant is very particular about the type of crops they cultivate. Most varieties descend from a type of fungus that the ancestors of fungus-growing ants began growing some 55 million to 65 million years ago. Some of these fungi became domesticated and are now unable to survive on their own without their insect farmers, much like some human crops such as maize.

Ants started farming tens of millions of years before humans.

Ant farmers face many of the same challenges human farmers do, including the threat of pests. A parasite called Escovopsis can devastate ant gardens, causing the ants to starve. Likewise in human agriculture, pest outbreaks have contributed to disasters like the Irish Potato Famine, the 1970 corn blight and the current threat to bananas.

Since the 1950s, human agriculture has become industrialized and relies on monoculture, or growing large amounts of the same variety of crop in a single place. Yet monoculture makes crops more vulnerable to pests because it is easier to destroy an entire field of genetically identical plants than a more diverse one.

Industrial agriculture has looked to chemical pesticides as a partial solution, turning agricultural pest management into a billion-dollar industry. The trouble with this approach is that pests can evolve new ways to get around pesticides faster than researchers can…