In our endless search to understand the Universe and our place within it, precious little blips in data can hint at entire new worlds.

Dips in the light levels of a star can betray the presence of orbiting planets – and now astronomers have taken the first steps towards using peeps of radio emission to reveal new exoplanetary mysteries.

“Observing planetary auroral radio emission is the most promising method to detect exoplanetary magnetic fields,” explained Cornell University astronomer Jake Turner and colleagues in their new paper, “the knowledge of which will provide valuable insights into the planet’s interior structure, atmospheric escape, and habitability.”

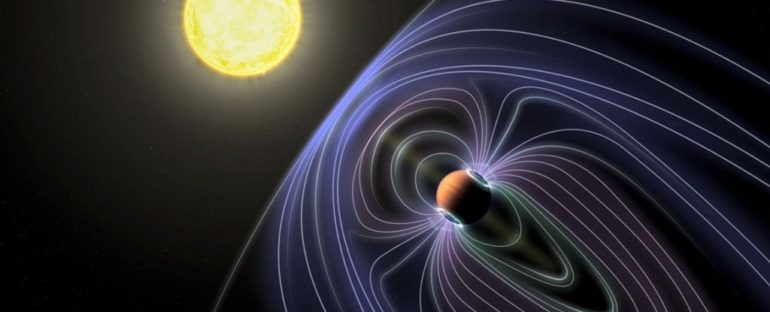

When stellar wind – charged particles streaming from the host star – hits a planet’s magnetic field, its change in speed can be detected as striking variations in radio emissions, statistically described as ‘bursty’.

Earth’s own magnetic field trills and squeaks like alien birds as it channels solar winds. We’ve also heard similar cries from other planets in our Solar System.

Of course, to detect a whisper of such radio signals coming from an exoplanet, we first need a way to look beyond all the noise from Earth and elsewhere.

A few years ago, the team developed the BOREALIS pipeline program to do just that. They tested it on Jupiter and then calculated what Jupiter’s radio emissions would look like if it were much farther away.

There have already been some tentative detections of new planets using these radio emissions, including early this year when astronomers linked radio wave activity to interactions between star GJ 1151’s magnetic field and a potential Earth-sized planet. But these have all yet to be confirmed by follow-up radio observations.

So Turner’s team decided to test the technique they developed, using Netherland’s Low Frequency Array Radiotelescope (LOFAR) to look at three systems with known exoplanets: 55 Cancri, Upsilon Andromedae, and Tau Boötis.

Only the Tau Boötis system, 51 light years away, exhibited the peeps in radio data that fit the researchers’ predictions from their tests with Jupiter. It came in the form of 14-21 MHz bursty emissions and is within roughly three standard deviations of certainty (3.2 sigma).

In 1996, a hot-Jupiter exoplanet was discovered on a 3.3128-day orbit around the scorching young F-type star and the smaller red dwarf that make up the Tau Boötis binary system.

“We make the case for an emission by the planet itself,” said Turner. “From the strength and polarisation of the radio signal and the planet’s magnetic field, it is compatible with theoretical predictions.”

If their measurements are correct, they suggest the planet’s surface magnetic field strength ranges from around 5 to 11 gauss (Jupiter ranges from 4 to 13 gauss, for comparison); and measurements of its magnetic field have revealed the planet has a core of metallic hydrogen. The observed magnetic field emission strength also fits previous predictions.

“The magnetic field of Earth-like exoplanets may contribute to their possible habitability,” Turner explained, “by shielding their own atmospheres from solar wind and cosmic rays, and protecting the planet from atmospheric loss.”

The signal they detected is weak and still needs to be verified by other low-frequency telescopes before researchers can confirm the true origin of the detected radio emissions.

“We cannot rule out stellar flares as the source of the emissions,” the researchers cautioned, but emissions from the planet remain a possibility.

If other telescopes like LOFAR-LBA and NenuFAR can corroborate these findings, such radio emission detections from exoplanets will open up an exciting new field of research, providing us with a potential way to peer further into distant, alien worlds.

This research was published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.