If they’re in your area, you’ll know it from their loud droning, chirping and buzzing sounds. Cicadas from Brood XIV – one of the largest groups of cicadas that emerge from underground on a 13-year or 17-year cycle – are surfacing in May and June 2025 across 12 states. This large-scale biological event reaches from northern Georgia up into Indiana and Ohio and eastward through the mid-Atlantic, extending as far north as Long Island, N.Y. and Massachusetts.

Through mid-June, wooded areas will ring with cicadas’ loud mating calls. After mating, each female will lay hundreds of eggs inside small tree branches. Then the adult cicadas will die. When the eggs hatch six weeks later, new cicada nymphs will fall from the trees and burrow back underground, starting the cycle again.

We are evolutionary ecologists who study periodical cicadas to understand questions about the natural history, genetics and geographic distribution of life. This work starts with mapping where they appear.

We’ve been doing this for decades, updating a process begun by entomologists in the mid-1800s. Our latest maps are published online and searchable.

Periodical cicadas emerge on 13- or 17-year cycles in enormous numbers, which increases their odds of finding mates and avoiding predators long enough to reproduce.

Mapping the presence of such a noisy species might seem straightforward, but it’s actually complex. And accuracy matters because there are seven species of periodical cicadas — four with 13-year life cycles and three with 17-year cycles. Different broods can share boundaries, and some cicadas that emerge this year may be members of broods other than XIV, coming out early or late.

A lot of work goes into verifying the data in our maps so that they show the status of these unique insects as accurately as possible. Here’s a look at the process, and at how you can contribute:

Refining past records

We first started creating our maps on paper by collecting all known specimen records of 13- and 17-year periodical cicadas from past scientific studies and museums large and small across the eastern U.S., where these broods are located. For centuries, museum specimens have been the gold standard for documenting the presence of a species.

But past standards for labeling specimens were different. Many old museum labels simply noted very approximate locations where specimens were collected. Sometimes they just recorded the city, county or state.

Today we collect our records along roads. We listen for species-specific songs and then record the cicada species identity on computers, with their GPS locations. Often we’ll stop to examine a patch of forest. If the cicadas are singing, we note whether the chorus is light, moderate, loud or distant.

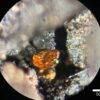

If stormy weather damps down the cicada songs, we look for signs of emergence, such as cast-off skins, adult cicadas on plants, or…