A group of international scientists—including two from the University of Plymouth and Plymouth Marine Laboratory (PML)—has developed a new method for examining the effects of artificial light at night (ALAN) on two sandy beach crustacean species.

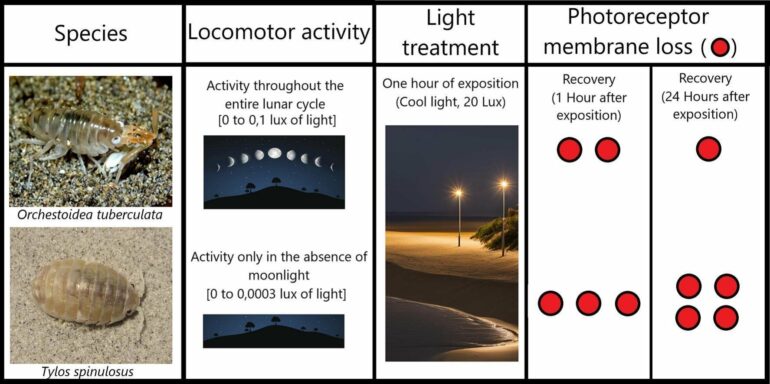

The study focused on sandhoppers (Orchestoidea tuberculate) and beach pillbugs (Tylos spinulosus), using tiny slices of their tissue and powerful microscope techniques to measure these species’ visual systems and assess damage caused by artificial lighting.

The study is published in the journal Science of the Total Environment, and was led by researchers from the Universidad Andrés Bello in Chile.

In isopods such as the beach pillbug, which are naturally adapted to dimmer night lighting compared to amphipods like sandhoppers, the light-sensitive part of the eye (rhabdom) is 20 times larger and includes a reflective layer called a tapetum, which helps species in low-light environments.

A short exposure to artificial light caused between three and six times more damage to the beach pillbug’s rhabdom compared to the sandhopper’s, with no recovery after as much as 24 hours.

The isopod’s rhabdom showed structural damage, while the amphipod’s rhabdom was unaffected, suggesting that species adapted to darker environments are more severely and permanently affected by artificial light, potentially creating new challenges for their survival and evolution.

The researchers say their novel methodology has provided unprecedented insights into the microscopic world of marine crustacean photoreceptors, suggesting that ALAN can result in the disruption of natural behavioral patterns and potential genetic modifications in light-sensitive species.

While the extent and ecological impacts of light pollution are increasingly well understood in the marine environment, current research is often restricted to measuring changes in the behavior of organisms or how they are assembled within a habitat.

“This study provides evidence of the direct damage caused by light pollution to the visual capabilities of an animal. Not only does it highlight how light pollution causes harm to marine species directly, but it also raises new concerns around the impacts of lighting associated with deep sea exploration and development.

“These regions of our oceans experience little or no light and so many animal visual systems are likely to be very sensitive to low light conditions and more easily damaged by lights that otherwise wouldn’t be there,” says Dr. Thomas Davies.

“We already know that artificial light is detected at around a quarter of the world’s coasts and will dramatically increase as coastal human populations more than double by the year 2060. This latest study shows the devastating potential effects it can have on tiny creatures found along the shoreline, which are important food sources and habitat engineers, and how urban lighting can fundamentally alter their sensory systems,” says Professor Steve Widdicombe.

The University and PML have partnered on a number of pioneering studies into the impacts of marine light pollution in recent years.

In April 2024, they launched the Global Ocean Artificial Light at Night Network (GOALANN) at the United Nations Ocean Decade Conference in Barcelona, aiming to unify research groups from around the world to provide a central resource of marine light pollution expertise, projects and tools.

More information:

C. Miranda-Benabarre et al, Crustacean photoreceptor damage and recovery: Applying a novel scanning electronic microscopy protocol in artificial light studies, Science of The Total Environment (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.177561

Provided by

University of Plymouth

Citation:

Blinded by the light: The effects of urban lighting on beach bugs (2024, December 18)