The ability of most mammals to maintain a relatively constant and high body temperature is considered a key adaptation, enabling them to successfully colonize new habitats and harsh environments. Eager to determine how this ability evolved, some scientists proposed that a particular region of the mammal skull—the anterior nasal cavity, which houses structures known as the maxilloturbinals—plays a pivotal role in body temperature maintenance.

But a study in Nature Communications cautions against using the presence and relative size of these skull structures to determine if an animal—living or extinct—is capable of maintaining heat and moisture for survival.

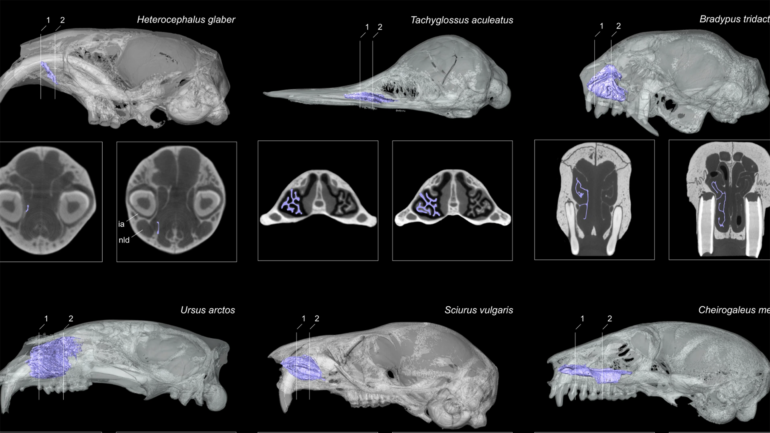

Biologist Stan Braude in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis is a co-author of the study. His team’s findings are based on an analysis of CT scans of the heads of more than 300 mammals from international museum collections.

“Our respiratory turbinals do help humans and other mammals warm the air we inhale, as well as conserve water from the air we exhale,” Braude said.

“This project doesn’t change how I teach this in my ‘Human Anatomy and Physiology’ course at Washington University. But the size of the underlying bony structures (the maxilloturbinals) does not correlate with metabolic rate or body temperature. This is likely because mammals live in such diverse environments and have various other adaptations to those conditions.”

“The dogma that maxilloturbinals in fossil species indicates their ability to maintain body temperature—i.e. homeothermy—is oversimplified and unjustified,” Braude said.

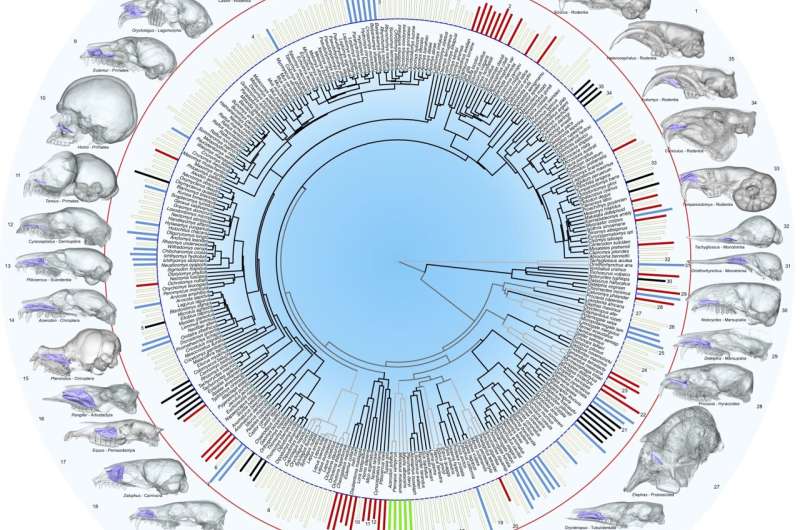

Variations of the relative surface area and shape of the maxilloturbinal between mammalian species. Barplots represent the relative surface area of the maxilloturbinal in 310 species. Blue and red circles respectively represent the minimum and the maximum values from the naked mole-rat (Heterocephalus glaber) and the California sea lion (Zalophus californianus). 3D representations of the skull and the maxilloturbinal in several species. Barplots: cream = terrestrial, red = arboreal, blue = amphibious, black = subterranean, and green = flying species. Not to scale. © Nature Communications (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-39994-1

More information:

Quentin Martinez et al, Mammalian maxilloturbinal evolution does not reflect thermal biology, Nature Communications (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-39994-1

Provided by

Washington University in St. Louis

Citation:

Fossil skulls alone cannot predict if animal was warm blooded, study finds (2023, July 28)