In collaboration with a foundation that breeds service dogs for the visually impaired, researchers at the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Padova in Padova, Italy, have identified a novel variant associated with progressive retinal atrophy in three Labrador retrievers.

In most animals, humans included, vision starts in the retina, where the layers of cells at the back of the eye receive light and convert it into electrical signals that are sent to the brain to create the visual images that are “seen.” Disruption to this process, often the result of inherited retinal diseases (IRDs), can lead to a variety of visual impairments, including blindness, in humans and other mammals such as dogs.

In a recent study published in Scientific Reports, researchers at Penn Vet and the University of Padova in Padova, Italy, found a genetic mutation in three Labrador retriever littermates affected by progressive retinal atrophy, the most common classification of IRDs in dogs.

These dogs were brought to the attention of Leonardo Murgiano and Gustavo D. Aguirre of Penn Vet and their collaborators by a foundation that breeds service dogs for the visually impaired.

“We have been providing services to guide dog organizations since 1989,” says Aguirre. “When these organizations reach out to us, our aim is to find the mutation and develop a diagnostic test for it so that they can use it to breed dogs without this condition in the future.”

Specifically, in this study, the researchers identified a 3-bp deletion in the coding region of GTPBP2, a gene that encodes a G-protein expressed in several tissues—including the canine retina. They found that this deletion was linked to the loss of a highly conserved alanine well outside of the GTPase domain of GTPBP2, where the activity of the protein is regulated, toggling it “on” and “off.” Therefore, this finding indicates that loss of this alanine affects a different aspect of the protein, possibly its cellular localization.

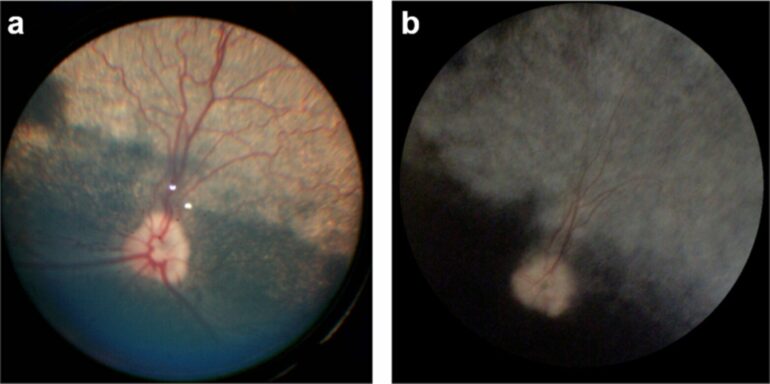

![Cellular localization of normal (wild-type [WT]) and A536del mutant GTPBP2 proteins. Cells were transfected with WT (a,b) or with A536del mutated GTPBP2 cDNAs (c,d). © Eylem Emek Akyürek and Roberta Sacchetto; courtesy of Leonardo Murgiano and Gustavo D. Aguirre New genetic cause of blindness in dogs](https://techandsciencepost.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Genetic-mutation-in-Labradors-reveals-new-cause-of-canine-blindness.jpg)

Cellular localization of normal (wild-type [WT]) and A536del mutant GTPBP2 proteins. Cells were transfected with WT (a,b) or with A536del mutated GTPBP2 cDNAs (c,d). © Eylem Emek Akyürek and Roberta Sacchetto; courtesy of Leonardo Murgiano and Gustavo D. Aguirre

An analysis of 91 non-affected Labrador retrievers from the same kennel and 569 from the general U.S. population identified 16 carriers—all from the original kennel. All other dogs were wild-type—that is, they carried the “normal” version of the gene—highlighting the rarity of this variant.

Mutations in this gene have also been reported in humans; however, these human GTPBP2 genetic variants are associated with Jaberi-Elahi syndrome—human patients typically have neurologic abnormalities such as motor alterations, seizures, and intellectual disabilities as well as general morphologic abnormalities. In contrast, the affected dogs in this study showed no other symptoms other than retinal degeneration/blindness.

“What we report here is a variant that appears to be less severe in our dogs than what is reported in humans, possibly occurring in a different region of the protein—closer to its terminal part,” explains Murgiano.

“We have observed this before in genes attributed to syndromes—not all mutations in those genes lead to syndromes. Phenotypes can be flexible, and what we report here is an example of a flexible phenotype. This could have relevance in a general medical genetics landscape.”

More information:

Leonardo Murgiano et al, GTPBP2 in-frame deletion in canine model with non-syndromic progressive retinal atrophy, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-89446-7

Provided by

University of Pennsylvania

Citation:

Genetic mutation in Labradors reveals new cause of canine blindness (2025, March 21)