By statistically analyzing data from around the world, scientists have determined that multiple natural and human stressors are reducing levels of biodiversity and soil functioning in soil ecosystems. The number and specific combination of those stressors are determining factors in this interaction. This is the conclusion that has been reached by an international team of scientists led by Matthias C. Rillig, a biology professor at Freie Universität.

The results of their study have now been published in Nature Climate Change, titled “Increasing the Number of Stressors Reduces Soil Ecosystem Services Worldwide.”

To survive, soils and terrestrial ecosystems around the world must contend with a wide range of natural and human stressors. These include droughts, warming, and exposure to harmful chemical substances, including microplastics. It is not only the type of stressor, but also the number of them (in particular, those caused by human activity) that have a negative effect on various processes in the soil.

“Our earlier laboratory-based studies have shown that an increased number of global change factors led to a reduction in soil processes such as decomposition, soil aggregation, and soil respiration, as well as to a reduction in the biodiversity of the soil,” says Professor Rillig, lead author of the study and head of the research team, which also included Spanish ecologist Dr. Manuel Delgado-Baquerizo.

The research team analyzed two global standardized field surveys on soils and a range of natural and human factors known to affect soil ecosystems.

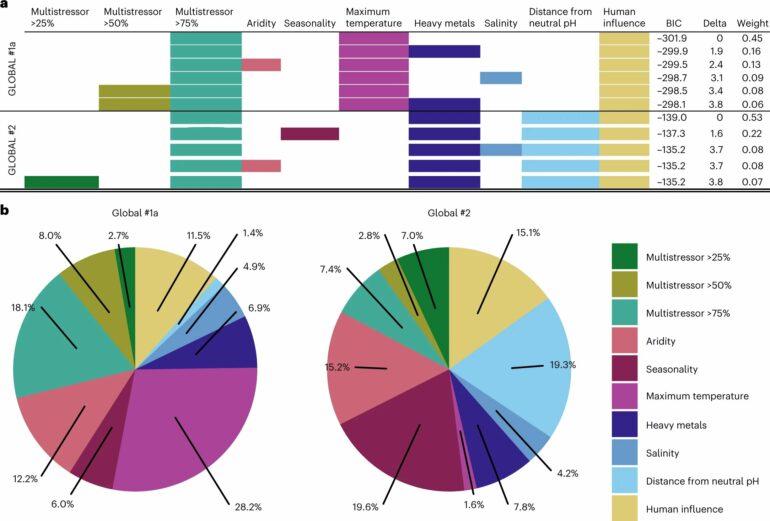

“Our study evaluated soil ecosystems by categorizing fifteen ecosystem variables into six main types of ecosystem services: organic-matter decomposition, soil biodiversity, pathogen control, plant productivity, water regulation, and nutrient cycling. For the purposes of the study, we defined seven important environmental variables as stressors. These were chosen based on their potential to cause environmental stress when they reach high levels: aridity, temperature, seasonality, salinity, distance from neutral pH, levels of heavy metals, and human influence. We also took the level of pesticides and microplastics in the soil into account, as data were available on these for a subset of locations in one of the global field surveys,” explains Rillig.

In order to investigate the number of stressors as parameters in the study, data from the global field surveys first had to be converted into a variable that reflected the number of factors. To do so, the researchers counted the number of environmental stressors that passed a given threshold value.

The number of stressors was considered to have passed a threshold when these exceeded 75 percent of maximum stressor levels. The investigation demonstrated that an increased number of factors above a certain threshold reduced the soils’ capacity to support ecosystem services.

“This increasing number of threshold-exceeding stressors could explain soil reactions that, to date, could not be attributed to the type of stressors alone,” says Rillig. Additionally, the results of the study demonstrated that “humans must reduce their impact on ecosystems by decreasing the number of factors that negatively affect soil processes and soil biodiversity.”

The combination of human influences collectively affects soil processes and soil ecosystem biodiversity. “If the extent of this problem, i.e., the number of stressors that exceed a critical threshold, is not reduced, we run the risk of losing important ecosystem services,” says Rillig.

At the same time, Rillig notes that the study took a primarily observational approach. This means that the researchers were able to discover patterns but could not draw any direct conclusions regarding causality. Additional research will be required to explain the connection between the number of stressors and the ecosystem’s reaction. The effects of multiple concurrent factors on other types of ecosystems (for example, aquatic systems) could also provide a potential future avenue of study.

More information:

Matthias C. Rillig et al, Increasing the number of stressors reduces soil ecosystem services worldwide, Nature Climate Change (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-023-01627-2

Provided by

Freie Universitaet Berlin

Citation:

Global analysis shows soil ecosystems under stress (2023, March 28)