Giant clams, some of the largest mollusks on Earth, have long fascinated scientists. These impressive creatures can grow up to 4.5 feet in length and weigh over 700 pounds, making them icons of tropical coral reefs.

But these animals don’t bulk up on a high-protein diet. Instead, they rely largely on energy produced by algae living inside them. In a new study led by CU Boulder, scientists sequenced the genome of the most widespread species of giant clam, Tridacna maxima, to reveal how these creatures adapted their genome to coexist with algae.

The findings, published in the journal Communications Biology, offer clues about how such evolution may have contributed to the giant clam’s size.

“Giant clams are keystone species in many marine habitats,” said Jingchun Li, the paper’s senior author and professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. “Understanding their genetics and ecology helps us better understand the coral reef ecosystem.”

A symbiotic relationship

Unlike popular myths—like the one in Disney’s “Moana 2” where the giant clam eats humans—these vegetarian mollusks rely on algae living within their bodies for energy. If giant clams ingest the right algae species while swimming through the ocean as larvae, they develop a system of tube-like structures coated with these algae inside their bodies. These algae can turn sunlight into sugar through photosynthesis, providing nutrients for the clams.

“It’s like the algae are seeds, and a tree grows out of the clam’s stomach,” Li said.

At the same time, the clams shield the algae from the sun’s radiation and give them other essential nutrients. This mutually beneficial relationship is known as photosymbiosis.

“It’s interesting that many of giant clams’ cousin species don’t rely on symbiosis, so we want to know why giant clams are special,” said Li.

In collaboration with researchers at the University of Guam and the Western Australian Museum, the team compared the genes of T. maxima with closely related species—such as the common cockle—that lack symbiotic partners.

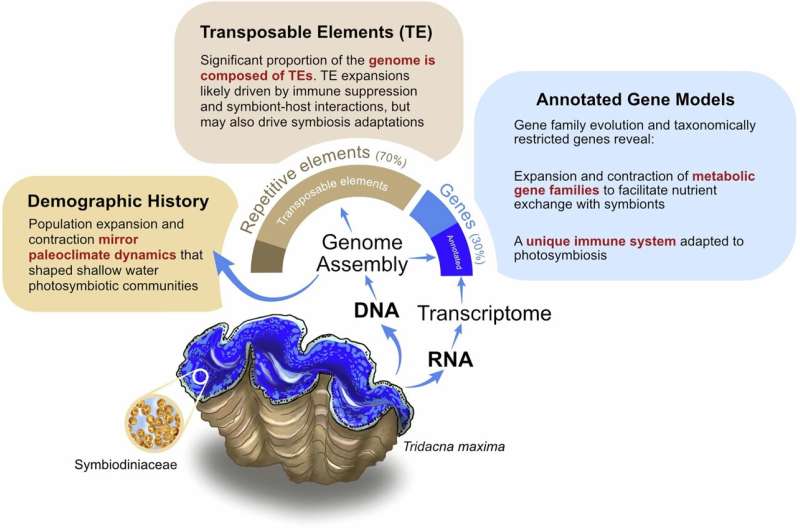

The researchers found that T. maxima have evolved more genes coded for sensors to distinguish friendly algae from harmful bacteria and viruses. At the same time, T. maxima has tuned down some of its immune genes in a way that likely helps the animals tolerate algae living in their bodies long term, according to Ruiqi Li, the paper’s first author and postdoctoral researcher at the CU Museum of Natural History.

Summary of major findings in this study. © Communications Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-024-07423-8

As a result of the clam’s weakened immune system, its genome contains a large number of transposable elements, which are bits of genetic material left behind by ancient viruses.

“These aspects highlight the tradeoffs of symbiosis. The host has to accommodate a suppressed immune system and potentially more viral genome invasions,” said Ruiqi Li.

The study also discovered that giant clams have fewer genes related to body weight control, known as the CTRP genes. Having fewer CTRP genes might have allowed giant clams to grow larger.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

Conservation concerns

Last year, a giant clam population assessment by Ruiqi Li, prompted the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to update the conservation status of multiple giant clam species. Tridacna gigas, the largest and most well-known species, is now recognized as “critically endangered,” the highest level before a species becomes extinct in the wild.

T. maxima, because of its wide distribution, is currently classified as “least concern.” But Ruiqi Li says it’s possible that different species are lumped into one category simply because they look similar.

“If you think these giant clams are all the same species, you might underestimate the threat they face,” Ruiqi Li said. “Genetic studies like this can help us distinguish between species and assess their true conservation needs.”

The team hopes to sequence the genomes of all 12 known species of giant clams to better understand their diversity.

Similar to corals, giant clams are facing increasing threats from climate change. When the ocean water becomes too warm, the clams expel the symbiotic algae from their tissues. Without the algae, the giant clams could starve.

“The giant clams are very important for the stability of the marine ecosystem and support biodiversity,” Jingchun Li said. She added that many creatures living in the shallow waters rely on their shells for shelter, and giant clams also provide food for other organisms.

“Protecting them is essential for the health of coral reefs and the marine life that depends on them.”

More information:

Ruiqi Li et al, Photosymbiosis shaped animal genome architecture and gene evolution as revealed in giant clams, Communications Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-024-07423-8

Provided by

University of Colorado at Boulder

Citation:

How tiny algae shaped the evolution of giant clams (2025, January 27)