A new study by researchers at the UT sheds light on historical changes in the amount of water humanity consumes to grow the world’s main crops. The analysis demonstrates that despite increasing crop water productivity, the total amount of water we consume keeps growing, which may exacerbate the already existing myriad of related environmental and socio-economic issues.

The study, published in Environmental Research Letters, looks at 175 crops from the 1990–2019 period in terms of their green and blue water footprints. Green water refers to water coming from rainfall and blue water comes from irrigation and shallow groundwater.

“We need to differentiate between these two water types as they play different roles in ecosystems and society,” says Oleksandr Mialyk, a postdoctoral researcher at the Multidisciplinary Water Management group.

Nearly 80% of analyzed crops required less water per ton in 2019 compared to 1990. However, these productivity gains were insufficient to stop the global total water footprint of crop production from increasing. Since 1990, the latter has increased by almost 30% or 1.55 trillion m3. “Our estimate for 2019 stands at 6.8 trillion m3 of mainly green water, which is around 2,400 liters per person per day,” adds Mialyk.

What drives the increase

Close to 90% of the total increase occurred between 2000 and 2019 which the authors link to three main socio-economic drivers. First, accelerated globalization and economic growth substantially increased the consumption of various imported crops and crop products. Second, global diets shifted to more water-intensive products such as animal produce, sweetened drinks, and sugary & fatty foods. Third, the energy security and green agendas of many governments boosted the production of crop-based biofuels.

These socio-economic changes mostly favored the cultivation of flex crops or crops which can be processed into many diverse products (food, animal feed, biofuels, etc.). These crops allow farmers, investors, and insurers to reduce financial risks associated with crop production as diverse end-user markets ensure stable profits and return on investments.

Combined with active agricultural lobbyism, the production of these crops rapidly increased over the last decades. For example, just the three largest ones—oil palm fruit, soya beans, and maize—can explain half of the total increase in the total water footprint of crop production between 1990–2019.

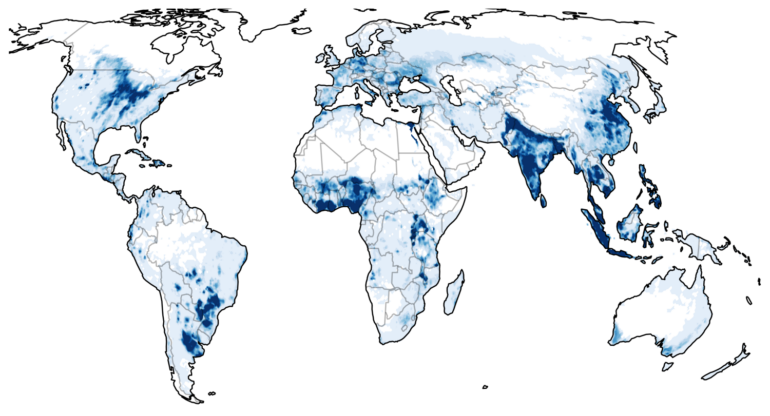

Hotspots of crop water consumption

India, China, and the U.S. are the largest water consumers according to the study. However, the total water footprint increase occurred mostly across the tropics, which often comes together with other environmental impacts, including deforestation and biodiversity loss.

“This region offers optimal geographical conditions for crop production while favorable agricultural policies attract investments from large agrifood corporations,” explain the authors. As a result, some regions became increasingly specialized in a small range of water-intensive crops, like oil palm fruit in Indonesia or soya beans and sugar cane in Brazil.

What’s next?

“Our data suggests that humanity will keep increasing water consumption for crop production in the following decades,” says Mialyk. More crops will be produced, putting more pressure on limited green and blue water resources worldwide. However, there might be a more optimistic scenario.

The authors suggest that a lot of potential remains in increasing crop water productivity, shifting production to less water-scarce regions, wider adoption of less water-intensive diets, and minimizing the need for first-generation biofuels.

“Our research shows that we have many problems and now it is time to work on the solutions for a more water-sustainable future of crop production.”

More information:

Oleksandr Mialyk et al, Evolution of global water footprints of crop production in 1990–2019, Environmental Research Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ad78e9

Provided by

University of Twente

Citation:

Humanity consumes nearly seven trillion cubic meters of water per year to grow crops worldwide: Study (2024, October 28)