Climate change and asteroids are linked with animal origin and extinction—and plate tectonics also seems to play a key evolutionary role, “groundbreaking” new fossil research reveals.

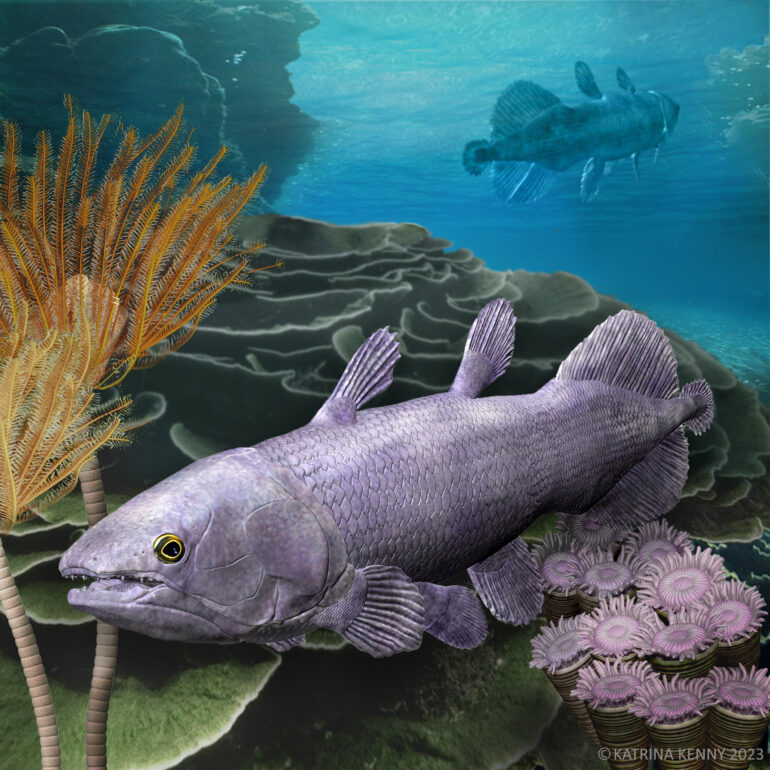

The discovery of an exceptionally well preserved ancient primitive Devonian coelacanth fish in remote Western Australia has been linked to a period of heightened tectonic activity, or movement in the Earth’s crust, according to the new study in Nature Communications.

Led by Flinders University and experts from Canada, Australia and Europe, the new fossil from the Gogo Formation in WA, named Ngamugawi wirngarri, also helps to fill in an important transition period in coelacanth history, between the most primitive forms and other more “anatomically-modern” forms.

“We are thrilled to work with people of the Mimbi community to grace this beautiful new fish with the first name taken from the Gooniyandi language,” says first author Dr. Alice Clement, an evolutionary biologist and paleontologist from Flinders University.

“Our analyses found that tectonic plate activity had a profound influence on rates of coelacanth evolution. Namely that new species of coelacanth were more likely to evolve during periods of heightened tectonic activity as new habitats were divided and created,” she says.

The study confirms the Late Devonian Gogo Formation as one of the richest and best-preserved assemblages of fossil fishes and invertebrates on Earth.

Flinders University Strategic Professor of Palaeontology John Long says the fossil, dating from the Devonian Period (359–419 million years ago), “provides us with some great insight into the early anatomy of this lineage that eventually led to humans.”

“For more than 35 years, we have found several perfectly preserved 3D fish fossils from Gogo sites which have yielded many significant discoveries, including mineralized soft tissues and the origins of complex sexual reproduction in vertebrates,” says Professor Long.

“Our study of this new species led us to analyze the evolutionary history of all known coelacanths.”

Many parts of human anatomy originated in the Early Paleozoic (540–350 million years ago). This was when jaws, teeth, paired appendages, ossified brain-cases, intromittent genital organs, chambered hearts and paired lungs all appeared in early fishes.

“While now covered in dry rocky outcrops, the Gogo Formation on Gooniyandi Country in the Kimberley region of northern Western Australia was part of an ancient tropical reef teeming with more than 50 species of fish about 380 million years ago.

“We calculated the rates of evolution across their 410 million-year history. This revealed that coelacanth evolution has slowed down drastically since the time of the dinosaurs, but with a few intriguing exceptions,” explains Professor Long.

Today, the coelacanth is a fascinating deep-sea fish that lives off the coasts of eastern Africa and Indonesia and can reach up to 2m in length. They are “lobe-finned” fish, which means they have robust bones in their fins not too dissimilar to the bones in our own arms, and are thus considered to be more closely related to lungfish and tetrapods (the back-boned animals with arms and legs such as frogs, emus and mice) than most other fishes.

Over the past 410 million years, more than 175 species of coelacanths have been discovered across the globe. During the Mesozoic Era, the age of dinosaurs, coelacanths diversified significantly, with some species developing unusual body shapes. However, at the end of the Cretaceous Period, around 66 million years ago, they mysteriously disappeared from the fossil record.

The end Cretaceous extinction, sparked by the impact from a massive asteroid, wiped out approximately 75% of all life on Earth, including all of the non-avian (bird-like) dinosaurs. Thus, it was presumed that the coelacanth fishes had been swept up as a casualty of the same mass extinction event.

Professor John Long holding a fossil specimen. Photo courtesy: Flinders University. © Flinders University

Ngamugawi wirngarri coelacanth skull bones after they were acid etched out of rock at Museum Victoria, 2009. © J Long (Flinders University)

Flinders University vertebrate paleontologist Dr. Alice Clement looking at a model of a modern-day coelacanth and a 3D printed skull of the Ngamugawi wirngarri coelacanth. © Flinders University

But in 1938, people fishing off South Africa pulled up a large mysterious looking fish from the ocean depths, with the “lazarus” fish going on to gain cult status in the world of biological evolution.

Another senior co-author, vertebrate paleontologist Professor Richard Cloutier, from the University of Quebec in Rimouski (UQAR), says the new study challenges the idea that surviving coelacanths are the oldest “living fossils.”

“They first appear in the geological record more than 410 million years ago, with fragmentary fossils known from places like China and Australia. However, most of the early forms remain poorly known, making Ngamugawi wirngarri the best known Devonian coealacanth.

“As we slowly fill in the gaps, we can start to understand how living coelacanth species of Latimeria, which commonly are considered to be ‘living fossils,’ actually are continuing to evolve and might not deserve such an enigmatic title,” says Professor Cloutier, a previous honorary visiting scholar at Flinders University.

The study’s co-authors have affiliations with Mahasarakham University in Thailand, the South Australian Museum, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, University of Bristol, Curtin University in Western Australia and the WA Museum.

More information:

A Late Devonian coelacanth reconfigures actinistian phylogeny, disparity, and evolutionary dynamics’, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-51238-4

Provided by

Flinders University

Citation:

New fossil fish species scales up evidence of Earth’s evolutionary march (2024, September 12)