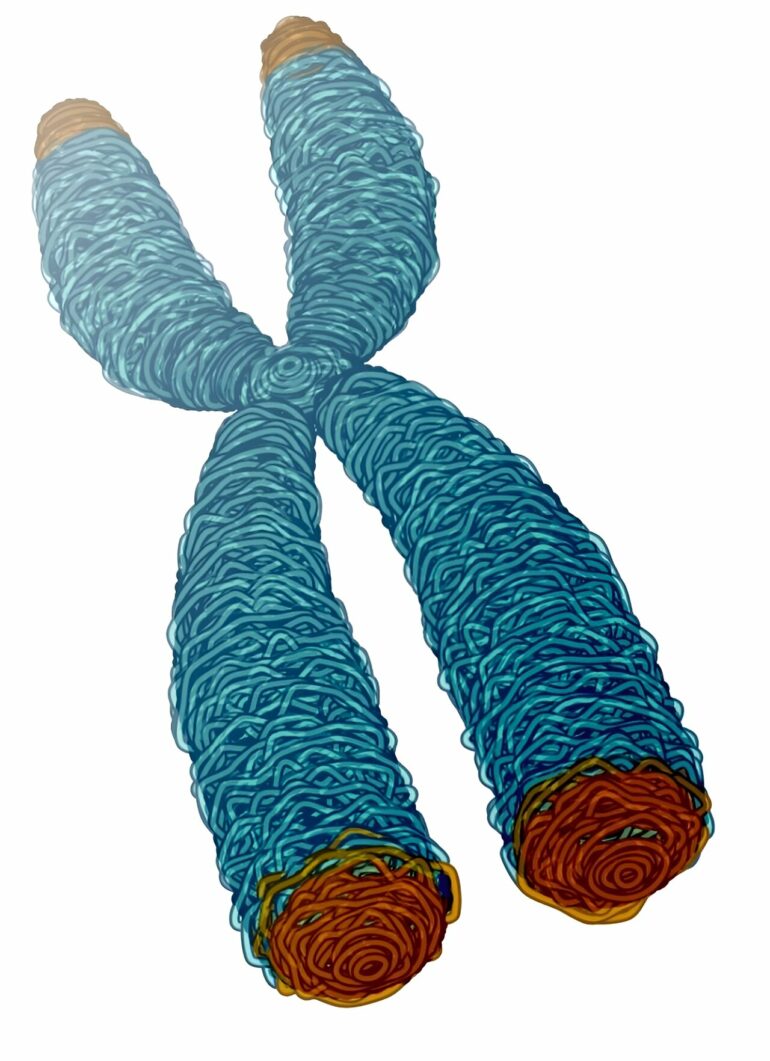

We depend on our cells being able to divide and multiply, whether it’s to replace sunburnt skin or replenish our blood supply and recover from injury. Chromosomes, which carry all of our genetic instructions, must be copied in a complete way during cell division. Telomeres, which cap the ends of chromosomes, play a critical role in this cell-renewal process—with a direct bearing on health and disease.

The enzyme telomerase plays a key role in maintaining the length of telomeres as chromosomes replicate during cell division. UC Santa Cruz professor Carol Greider has been studying telomeres and telomerase for over 30 years. The impact of the discoveries she has made over that time are why she, along with two colleagues, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2009.

So, the findings of Greider’s latest study on telomeres shouldn’t have surprised her. And yet, they did.

Published today in Science, a new study finds that telomere lengths follow a different pattern than has thus far been understood. Instead of telomere lengths falling under one general range of shortest to longest across all chromosomes, this study finds that different chromosomes have separate end-specific telomere-length distributions.

According to Greider, this discovery means we don’t fully understand the molecular process that regulates telomere lengths. That’s important because of how telomere lengths affect human health: “When telomeres get to be too short, you have age-related degenerative diseases like pulmonary fibrosis, bone-marrow failure, and immunosuppression,” Greider said. “On the other hand, if telomeres are too long, it predisposes you to certain types of cancer.”

Kayarash Karimian, the lead author on the paper, is a former Ph.D. student in Greider’s lab at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Other co-authors of this study include researchers at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, and University of Pittsburgh. Greider, a distinguished professor of molecular, cell, and developmental biology at UC Santa Cruz, and a University Professor at Johns Hopkins, was the senior author on the paper and led the work.

Why length matters

Without telomerase, telomeres would get shorter and shorter as a cell divides over and over again. Over the past 30 years, research by Greider and others have confirmed that short telomeres lead to degenerative disease—as well as shown that telomere lengths fall within a certain range.

But this paper challenges scientific consensus by showing that a singular telomere-length range is too broad. Measuring the telomeres of 147 people for this study, the researchers found in one individual that the average telomere length across all chromosomes was 4,300 bases of DNA. Then when they isolated specific chromosomes, they found most telomere lengths differed significantly from this average. In one case, lengths differed as much as 6,000 bases, which Greider describes as “jaw-dropping.”

Further, they found across all 147 individuals the same telomeres were most often the shortest or longest, implying telomeres on specific chromosome ends may be the first to trigger stem-cell failure.

Innovating on nanopore sequencing

To make such precise measurements at the molecular level, Greider’s team used a technique invented at UC Santa Cruz called “nanopore sequencing,” a revolutionary method for reading DNA and RNA that has had an immense impact on genomics research since its 2014 debut on the market as the commercial product MinION.

Nanopore technology has enabled some of the most significant advances in the genomics field, such as the completion of a gapless human genome, and sequencing of COVID-19 genomes—making it crucial in the fight to end the pandemic. UC Santa Cruz licensed the concept for nanopore-sequencing technology to the UK-based company Oxford Nanopore Technologies, which made MinION, the first hand-held DNA sequencer.

Notably, in the eyes of nanopore sequencing’s inventors, Greider’s study proves that the technique’s ability to advance scientific research continues to unfold. Mark Akeson, emeritus professor of biomolecular engineering at UC Santa Cruz, notes that two preprint studies that corroborate the basic findings of Greider’s paper have also been posted online.

“In my opinion, this is the most important nanopore-based paper focused on human biology since the MinION was introduced,” Akeson said. “It is easy to envision broad use of their telomere-length assay in the clinic.”

Akeson and David Deamer, also an emeritus professor of biomolecular engineering at the Baskin School of Engineering, were honored at the Library of Congress last year for inventing nanopore sequencing. Their colleague and friend Daniel Branton, a Havard biologist and co-inventor of the technology, was honored as well.

Implications for disease prevention

Such precise DNA reads allowed Greider’s team to pinpoint the sequences adjacent to telomeres and hypothesize that those areas are where telomerase is regulating length. And if that’s true, Greider said those regions, and the proteins that bind there, could serve as potential targets for new drugs for preventing disease.

In addition, their process of “telomere profiling” via nanopore sequencing could serve as a model for the development of additional MinION-based assays for high-throughput drug screening.

“This accessible technique has widespread potential for use in research, diagnostics, and drug development,” Greider said. “This work indicates that there are yet undiscovered mechanisms for telomere length regulation; probing these mechanisms will inform new approaches to cancer and certain degenerative diseases.”

More information:

Kayarash Karimian et al, Human telomere length is chromosome end–specific and conserved across individuals, Science (2024). DOI: 10.1126/science.ado0431

Provided by

University of California – Santa Cruz

Citation:

New study finds potential targets at chromosome ends for degenerative disease prevention (2024, April 11)