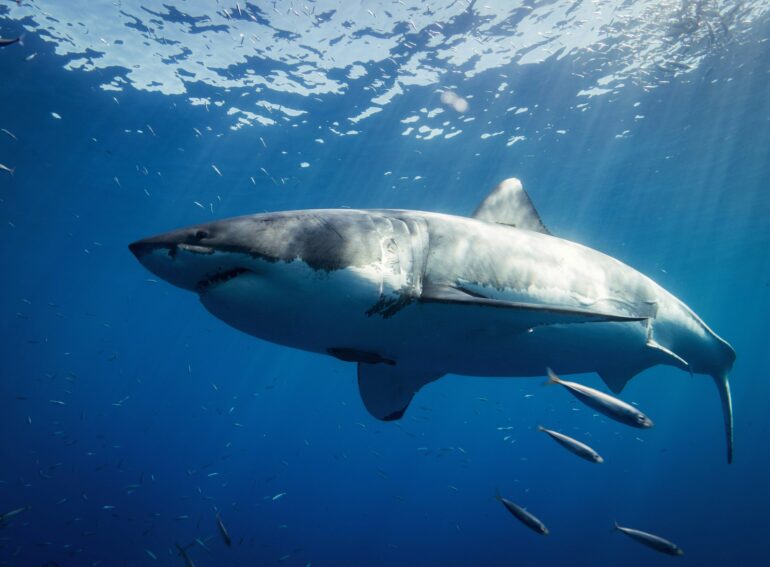

The Mediterranean Sea is a paradise. Pristine waters and an incredible coastline spanning multiple continents are renowned the world over. Below those picturesque, and sometimes crowded, waters swims a legendary creature facing a treacherous and uncertain future: the white shark.

Francesco Ferretti, an assistant professor in the College of Natural Resources and Environment, is working to save one of the most endangered white shark populations on the planet. The research team located signs of the remaining white sharks in the Sicilian Channel.

The research was published in Frontiers of Marine Science on Oct. 22, 2024.

“We decided to take on the challenge of locating the last remaining white sharks in the Mediterranean and saving them,” Ferretti said. “One of the most critical steps was tagging individuals so we could learn more about their abundance and distribution. This led to the ‘White Shark Chase,’ an initiative where we began identifying areas in the Mediterranean where these animals might be found. It was not easy as these sharks are rare.”

Incredibly rare, in fact.

Unlike places like California, where the sharks gather near seal colonies, they have no known aggregation areas in the Mediterranean. Finding them felt like searching for a needle in a haystack, or, more aptly, a grain of sand in the sea.

Taylor Chapple, an assistant professor at Oregon State University at the Coastal Oregon Marine Experiment Station and white shark technical expert on the project, was a postdoc with Ferretti at Stanford and they have continued to work together ever since.

“These animals likely have a very different ecology than the white sharks from other global populations,” Chapple said.

“These seem to be more likely based on tunas and smaller fish. It almost flips our understanding of white sharks on its head. It allows these animals that are a couple of tons—bigger than any land predators—to exist on a resource that is very surprising. Seals are very fatty, and these sharks are feeding on tuna and still getting this large.”

This research is the first step in establishing a monitoring program for the sharks in the region in the ongoing efforts to help prevent the animal’s extinction in the area.

The research was done in collaboration with Jeremy Jenrette and Brendan Shea of the Department of Fish and Wildlife; Shea and Austin Gallagher with Beneath the Waves; Chiara Gambardella with the Polytechnic University of Marche; Gambardella and Stefano Moro with Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn; Khaled Echwikhi with University of Gabes and High Institute of Applied Biology of Medenine; Robert Schallert and Barbara Block with Stanford University; Schallert with Tag-a-Giant; and Chapple with Oregon State University’s Coastal Oregon Marine Experiment Station.

Ferretti organized three pilot expeditions in 2021, 2022, and 2023, focusing on what we believed to be hotspots for the species—the Sicilian Channel. These expeditions used improved methods and technologies compared to previous efforts, such as environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling, which detects traces of animal DNA in water, like using a dog to sniff out an animal’s presence.

The researchers also used surface and deepwater cameras with bait to attract the sharks, and chumming to try and lure them closer.

During the expeditions, they detected the presence of white sharks on five occasions at the four sites. The team was correct in their choice of location and timing from May through June, but did not interact directly with the sharks.

“They are extremely sparse, and we realized that even with our efforts, we weren’t working on a large enough scale,” Ferretti said.

“We need to recalibrate our approach and develop new strategies. Despite these challenges, we were able to identify a stronghold of this population, particularly in the southern Sicilian Channel off northern Africa. This area is highly impacted by fishing, and it is where we are focusing our efforts now. The pilot expeditions allowed us to recalibrate for a larger program and provided valuable insight into where to focus future efforts.”

(From left) Brendan Shea, Chiara Gambardella, Francesco Ferretti, Jeremy Jenrette, Robert Schallert before departing for the “White Shark Chase” in 2021. © Francesco Ferretti

Stormy seas

The research team, which included graduate students from Virginia Tech, used leisure boats, which, while suitable, were far from ideal as they were not dedicated research vessels. They lacked space, speed, and the necessary equipment to properly store chum material—primarily bluefin tuna, which is highly regulated in the Mediterranean and difficult to source continuously.

“We were able to carry out our research, gathering vital data that will guide future expeditions,” Ferretti said. “It was a demanding but crucial part of our ongoing efforts to protect this endangered population.”

The journeys took the team from Marsala, on the northwest tip of Sicily, to various islands like Lampedusa and Pantelleria, as well as Tunisia and Malta, deploying long-line cameras and collecting eDNA samples along the way. However, the intense commercial boat and fishing traffic in the Sicilian Channel made things challenging, and the researchers had to monitor their equipment closely to avoid collisions with ships.

In 2023, the team utilized a large 87-foot sailing yacht to conduct open water research and had a film crew document the mission.

While they did not directly see any white sharks, they successfully tagged a Mako shark for the first time in the region as part of another research project.

And, Ferretti said, the path for future research missions has been set.

The next horizon

Now, the research team is planning and fundraising for multiple future expeditions in the Sicilian Channel and beyond.

“We know that one hot spot is there, but there may also be other important areas in the eastern Mediterranean Sea hosting critical habitat such as a nursery,” Ferretti said.

The researchers are implementing a series of approaches, including monitoring ports in North Africa to track interactions between fishers and sharks and collect biological material. This allows them to gather genetic and isotopic samples for analysis. Through isotopic analysis, they can learn more about the population’s structure, diet, and changes in habitat as the sharks grow.

“We don’t do research in a vacuum,” Chapple said.

“The research we do now is so multi-disciplinary and the questions that we can ask now are not achievable as a single entity. This white shark chase—there is so much knowledge held in local communities and stakeholders, that as a scientist we cannot step in there and say this is what we should do. These multi-institutional collaborations are critical for understanding the animals, the systems, and the culture that happens around the research.”

These collaborations across not only universities, but also regions, add additional tools to the researchers’ toolbox to improve effectiveness.

“We are expanding our network of local and international collaborators to maximize the value of the data we collect and establish a proper monitoring program for the Mediterranean,” Ferretti said.

“Currently, there is no formal monitoring or conservation program in place for this population. We want now to keep monitoring this population because we do not want to lose it.”

More information:

On the tracks of white sharks in the Mediterranean Sea, Frontiers in Marine Science (2024). DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1425511

Citation:

Pilot expeditions work to preserve the white shark in the Mediterranean Sea (2024, October 22)