Coral reef halos, also known as grazing halos or sand halos, are bands of bare, sandy seafloor that surround coral patch reefs. These features, clearly-visible from satellite imagery, may provide a window into reef health around the world, according to a recently published study by researchers at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST).

Scientists have observed reef halos for decades, mostly in the tropics, and explained their presence as the result of fish and invertebrates, who typically hide in a patch of coral, venturing out to eat algae and seagrass that cover the surrounding seabed. But the fear of predators keeps these smaller animals close to the safety of the reef—and focused on eating the marine plants nearby.

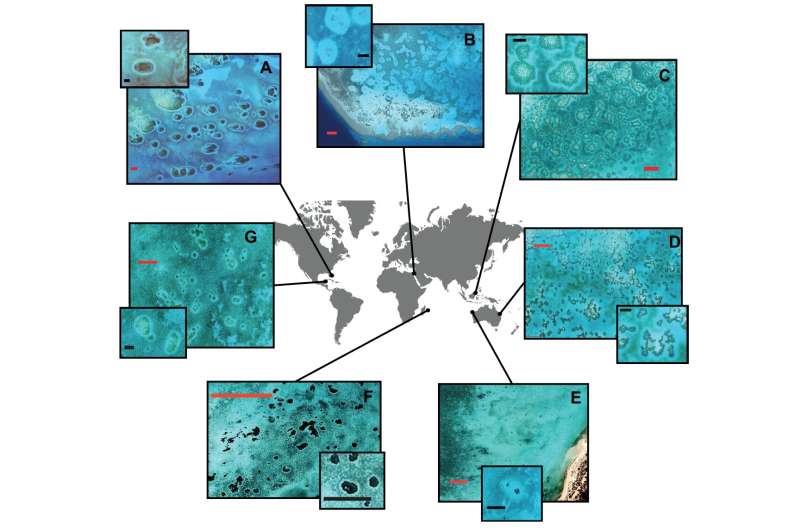

In the recently published study led by Elizabeth Madin, associate research professor at SOEST’s Hawai’i Institute of Marine Biology, the team analyzed very high resolution satellite imagery and historical aerial imagery from the 1960s from around the globe. They documented the previously-undescribed presence of halos outside of the tropics surrounding seagrass “reefs,” and revealed the timescales over which coral reef halos change, merge, and persist.

“We found that halos, a fascinating phenomenon occurring on coral reefs worldwide, are much more common around the world than we would have expected,” said Madin. “We also see that they are quite dynamic. Halos can change in size over relatively short timescales, on the order of months, despite persisting for at least half a century, which is as long as we could go back in time with aerial imagery.”

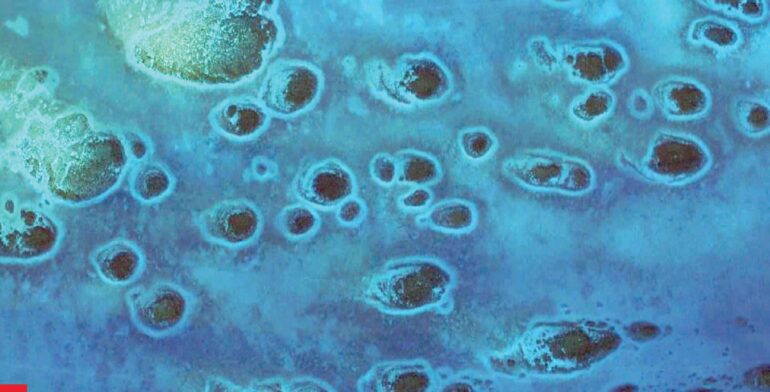

Halos surrounding seagrass ‘reefs’ within algal beds near Playa des Codolar, Ibiza Island, off the coast of Spain. © Google

Decoding indicators of health

Reef halos have been associated with marine reserves designed to protect predator and herbivore species from being overfished. Previous research published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences and Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution in 2019 indicated that halo presence is a potential indicator of predator—and possibly herbivore—recovery from fishing, and that halo size is likely indicative of herbivore recovery.

“Once we’ve been able to decode the clues that halos are giving us about the health of coral reef ecosystems, specifically in terms of the health of populations of plant- and fish-eating reef fishes, we plan to develop a tool that will allow scientists, reef managers, conservation practitioners, and others to remotely and cheaply survey coral reefs and understand how they’re doing,” said Madin.

“This approach will never fully replace underwater reef monitoring, but would provide a first-cut idea of how reefs are faring over much larger spatial and temporal scales than we can possibly achieve with traditional underwater surveys.”

Grazing halos are visible worldwide. © Compilation: Madin, et. al, 2022 via Google Earth Pro.

Madin and team have also just finished developing an artificial intelligence algorithm that will cut the time needed to find and measure halos from large volumes of satellite imagery from days to minutes. They are also exploring how predator populations around the world affect the presence and size of halos. And lastly, they are testing the mechanisms behind halo development and changes in size.

“All of this information will help us use halos as the basis for what we hope will be a valuable, freely-accessible, globally-relevant reef health assessment tool,” said Madin.

The new research is published in The American Naturalist.

More information:

E. M. P. Madin et al, Global Conservation Potential in Coral Reef Halos: Consistency over Space, Time, and Ecosystems Worldwide, The American Naturalist (2022). DOI: 10.1086/721436

Elizabeth M. P. Madin et al, Marine reserves shape seascapes on scales visible from space, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2019). DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2019.0053

Elizabeth M. P. Madin et al, Multi-Trophic Species Interactions Shape Seascape-Scale Coral Reef Vegetation Patterns, Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution (2019). DOI: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00102

Provided by

University of Hawaii at Manoa

Citation:

Reef halos may enable coral telehealth checkups worldwide (2022, October 24)