Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas is often associated with the induction of mutations. However, a team of researchers from the Swiss University of Lausanne now shows that it can also be used to repair natural mutations.

All living organisms mutate, which is a major driver of biodiversity and evolution. Humans have been domesticating plants for thousands of years, by selecting mutations that lead to favorable characteristics such as larger or more numerous fruits. However, this process often caused the co-selection of other undesirable mutations that can have negative effects on plant growth and development. This phenomenon is called the “cost of domestication.”

The selection and combination of mutations is also essential for breeding new crop varieties. To increase the frequency at which mutations occur, plants are exposed to chemicals or radiation. But this mutagenesis approach is random and makes breeding of new varieties very time-consuming.

Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas is a new approach to introduce mutations into the genome of plants in a precise and predictable manner. Even better, with genome editing it is not only possible to induce mutations, but also to repair existing ones: this was shown by researchers at the University of Lausanne in a paper published in Nature Genetics.

The biologists of the Department of Plant Molecular Biology (DBMV) at the Faculty of Biology and Medicine published their work on the second most consumed vegetable crop (or fruit for insiders) worldwide, after the potato: the tomato.

Using CRISPR to harvest earlier

Researchers in the laboratory of Sebastian Soyk, assistant professor at the DBMV, used a genome editing technology, called base editing, to change one of the ~850 million DNA base pairs in the genome of the tomato to repair an unfavorable domestication mutation. Anna Glaus, doctoral student in the research group, first selected and then investigated the mutated and repaired plants.

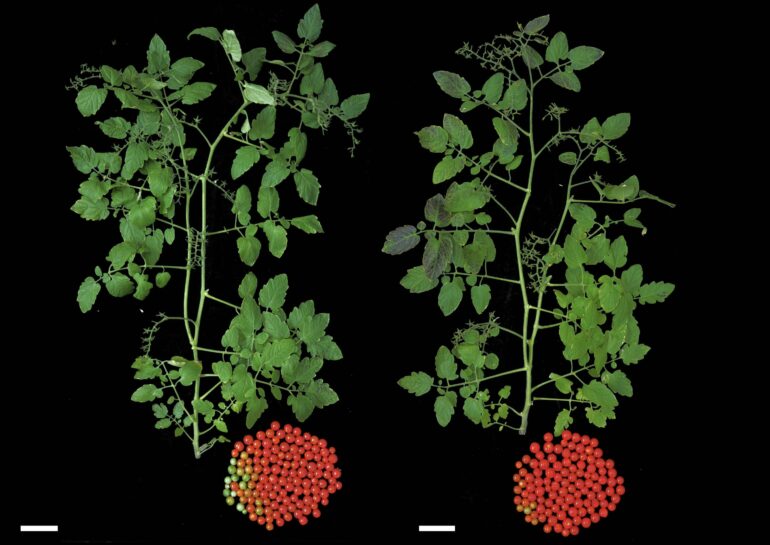

“To obtain these results, I characterized 72 plants and harvested during two consecutive days, 4,500 fruits that I sorted by size, weight, and maturity (red or green) and measured their sugar content,” explains Anna Glaus.

By repairing the deleterious domestication mutation with genome editing, the Swiss researchers have obtained a tomato variety that is earlier yielding.

Considering the Swiss moratorium banning the growth of genetically modified organisms (GMO), which expires in June 2025, this new study is thought-provoking.

“We show here the varied application of genome editing and its benefit for agriculture,” says Anna Glaus.

“It is important to take this scientific data into consideration when thinking about the legal frame of genome editing. With genome editing we now have the tools at hand to precisely re-write the genetic code and make crop breeding more predictable,” says Sebastian Soyk.

“We should now combine this ability with other directions in breeding and agricultural research, such as agroecology, to make agriculture more resilient and sustainable.”

More information:

Anna N. Glaus et al, Repairing a deleterious domestication variant in a floral regulator gene of tomato by base editing, Nature Genetics (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41588-024-02026-9

Provided by

University of Lausanne

Citation:

Repairing a domestication mutation in tomato leads to an earlier yield (2025, January 8)