Australian rock-wallabies are “little Napoleons” when it comes to compensating for small size, packing much more punch into their bite than larger relatives.

Researchers from Flinders University made the discovery while investigating how two dwarf species of rock-wallaby are able to feed themselves on the same kinds of foods as their much larger cousins. Study leader Dr. Rex Mitchell also coined the idea of “Little Wallaby Syndrome” after examining the skulls of dwarf rock-wallabies to discover that they can more than compensate for their size.

“We already knew that smaller animals have a harder time eating the same foods as larger ones, simply because their jaws are smaller. For example, a chihuahua wouldn’t be able to chew on a big bone as easily as a German Shepherd,” says Dr. Mitchell, from the Morphological Evo-Devo Lab at Flinders University. “If I were a vegetable, I would not mess with a pygmy rock-wallaby. They totally have ‘Little Wallaby Syndrome.'”

The team’s study, published in Biology Letters, delves deeper into the marsupials’ superpowers.

Co-author of the new study, Flinders University Associate Professor in Evolutionary Biology Vera Weisbecker, says some tiny species of rock-wallaby, such as the nabarlek, are able to eat similar foods as relatives that are eight times larger.

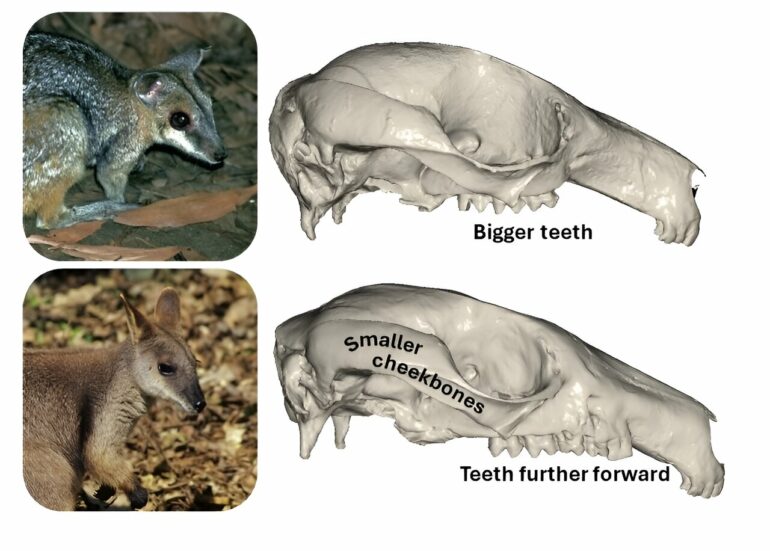

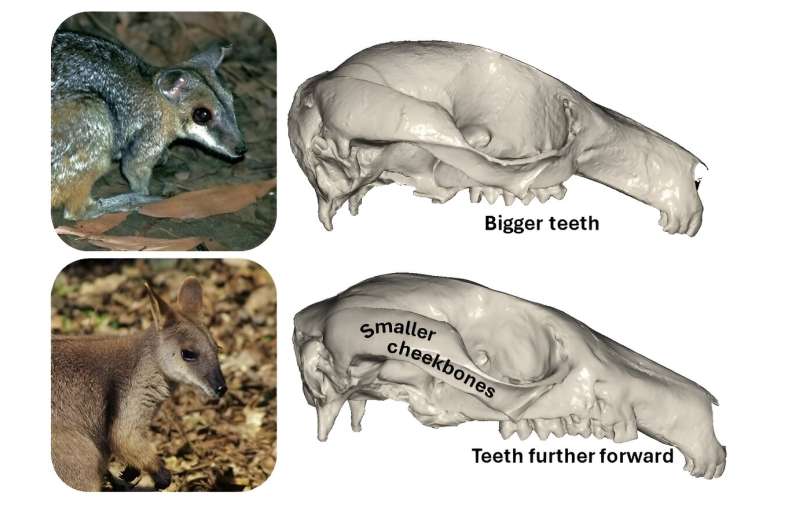

The skull of a pygmy rock-wallaby or nabarlek (above) and a Proserpine rock-wallaby (below). While the brain and eyes are larger in the dwarf species, they also have larger cheekbones and teeth positioned further back in the jaw. These features increase the ability to bite harder. © R Mitchell (Flinders University)

“We therefore suspected that something happened in the evolution of their jaws to allow them to stick to these diets,” she says.

To investigate, the researchers scanned the skulls of nearly 400 rock-wallaby skulls, including all 17 species, to compare the features of their skulls.

The results confirmed the team’s suspicions. Aside from typical differences in brain and eye size that are usually seen between larger and smaller animals, there were also differences in the features of the skull used for feeding.

Another co-author Dr. Mark Eldridge, from the Australian Museum, adds, “We found clear indicators that both dwarf rock-wallabies have adaptations to harder biting: They had shorter, rounder snouts and teeth positioned at the back of the jaw where they are more effective at harder bites.”

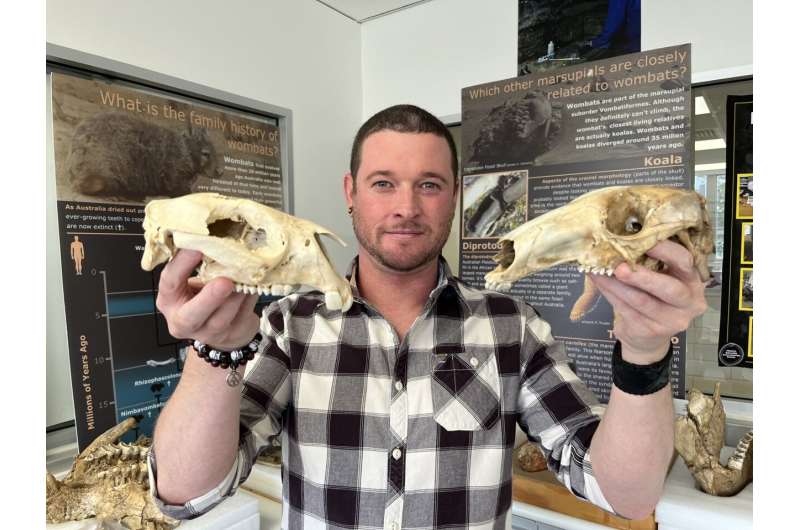

Researcher Dr. Rex Mitchell, in the Flinders University Palaeontology Lab, South Australia. © Flinders University

But the researchers also found some surprising differences in the teeth between the dwarfs and larger species. They found that some of the teeth of the dwarfs were much larger, for their size, than any of the bigger species.

“This makes sense, because many animals that need to bite harder into their foods tend to have bigger teeth for their size,” Dr. Mitchell says.

Moreover, dwarf wallabies had another surprise for the researchers: The two dwarf species had different teeth that were the biggest. One species has the biggest molars, while the other has the largest premolars.

These potentially indicate different adaptations to vegetation types. Larger premolars are better at slicing through leaves and twigs of shrubs, while larger molars are better for grinding up grass and other plants that are closer to the ground.

The species with the largest molars, the nabarlek, is the only species of marsupial known to continuously grow new molars throughout its life.

The findings show that dwarf species of rock-wallabies have skulls that are better at biting than larger species.

Dr. Mitchell says the findings are important because the functional effects of skull size on skull shape are often ignored, as differences in size are not generally considered to be related to feeding adaptations.

But the research team has shown that some differences in the skulls are related to how hard a skull can bite, and that smaller animals need to have harder-biting skulls than larger animals if they want to eat the same kinds of foods.

More information:

Functionally mediated cranial allometry evidenced in a genus of rock-wallabies, Biology Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2024.0045

Provided by

Flinders University

Citation:

Rock-wallabies are ‘little Napoleons’ when biting, thus compensating for their small size (2024, March 27)