Infectious or chronic diseases such as long COVID, Alzheimer’s disease and traumatic brain injury can cause inflammation in the brain, or neuroinflammation, that weakens muscles. While scientists are aware of this link between inflammation and muscle weakness, the molecules and processes involved have been unclear.

In our research, our team of neuroscientists and biologists uncovered the hidden conversation between the brain and muscles that triggers muscle fatigue, and potential ways to treat it.

Neuroinflammation and muscle fatigue

Neuroinflammation results when your central nervous system – the brain and spine – activates its own immune system to protect itself against infection, toxins, neurodegeneration and traumatic injury. Neuroinflammatory reactions primarily occur in the brain. But for unknown reasons, patients also experience many symptoms outside the central nervous system, such as debilitating fatigue and muscle pain.

To solve this puzzle, we studied brain inflammation in the context of three different diseases: bacterial infection in E. coli-induced meningitis; viral infection in COVID-19; and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Then, we analyzed how these immune changes affect muscle performance.

We measured immune changes in the brains of fruit flies and mice infected with live bacteria, viral proteins or neurotoxic proteins. After the initial accumulation of toxic molecules in the brain that commonly increase in response to stresses such as infection, the brain produces high levels of cytokines – chemicals that activate the immune system – that are released into the body. When these cytokines travel to muscles, they activate a series of chemical reactions that disrupts the ability of the powerhouse of cells – mitochondria – to produce energy.

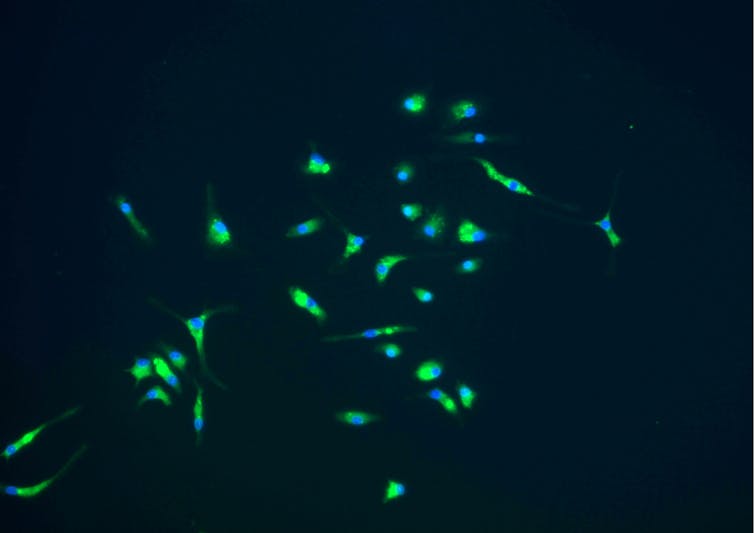

Microglia are cells that play a key role in the brain’s immune response.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH via Flickr

Though the result of these immune changes doesn’t seem to damage muscle fibers, it does cause fatigue. When we measured the muscle performance of these animals after giving them treatments to offset the effects of immune activation, we found that both flies and mice moved significantly less in response to manual or mechanical stimuli compared with those that were not infected. This indicated that the animals had reduced endurance.

Conversations between brain and muscle

Our findings suggest that the muscle fatigue that results from infection or chronic illness is caused by a brain-to-muscle communication pathway that depletes energy in muscles without disrupting their structure or integrity. Unlike traditional explanations for muscle dysfunction that focus on causes outside the brain, such as damage to the muscle fibers, this pathway directly causes fatigue.

Since the key cytokine involved in brain-to-muscle communication has been preserved throughout evolution across…