Researchers have long known that brain tumors, specifically a type of tumor called a glioma, can affect a person’s cognitive and physical function. Patients with glioblastoma, the most fatal type of brain tumor in adults, experience an especially drastic decline in quality of life. Glioblastomas are thought to impair normal brain functions by compressing and causing healthy tissue to swell, or competing with them for blood supply.

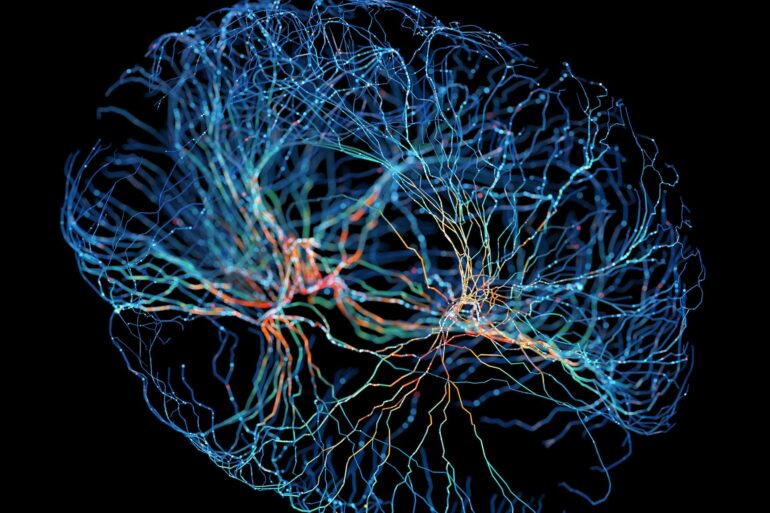

What exactly causes cognitive decline in brain tumor patients is still unknown. In our recently published research, we found that tumors can not only remodel neural circuits, but that brain activity itself can fuel tumor growth.

We are a neuroscientist and neurosurgeon team at the University of California, San Francisco. Our work focuses on understanding how brain tumors remodel neuronal circuits and how these changes affect language, motor and cognitive function. We discovered a previously unknown mechanism brain tumors use to hijack and modify brain circuitry that causes cognitive decline in patients with glioma.

Brain tumors in dialogue with surrounding cells

When we started this study, scientists had recently found that a self-perpetuating positive feedback loop powers brain tumors. The cycle begins when cancer cells produce substances that can act as neurotransmitters, proteins that help neurons communicate with each other. This surplus of neurotransmitters triggers neurons to become hyperactive and secrete chemicals that stimulate and accelerate the proliferation and growth of the cancer cells.

We wondered how this feedback loop affects the behavior and cognition of people with brain cancer. To study how glioblastomas engage with neuronal circuits in the human brain, we recorded the real-time brain activity of patients with gliomas as they were shown pictures of common objects or animals and asked to name what they depicted while they were undergoing brain surgery to remove the tumor.

Awake brain surgery involves mapping out the function of the areas of the brain around a tumor.

While the patients engaged in these tasks, the language networks in their brains were activated as expected. However, we found that the brain regions the tumors had infiltrated quite remote from known language zones of the brain were also activated during these tasks. This unexpected finding shows that tumors can hijack and restructure connections in the brain tissue surrounding them and increase their activity.

This may account for the cognitive decline frequently associated with the progression of gliomas. However, by directly recording the electrical activity of the brain using electrocorticography, we showed that despite being hyperactive, these remote brain regions had significantly reduced computational power. This was especially the case for processing more complex, less commonly used words, such as “rooster,” in comparison with simple,…