Nobody would ever have thought that farming the Atacama Desert would be easy.

Yet, even so, the brutal challenges of living off the land in one of the driest, harshest environments on Earth (and the driest non-polar desert) proved deadly to many, and not all of the dangers were imposed by the desert.

Some of the most formidable hazards here were the people themselves.

In a new study, researchers investigated the grisly human remains of some of the first horticulturalists who sought to cultivate the Atacama Desert in what we now know as Chile, roughly 3,000 years ago.

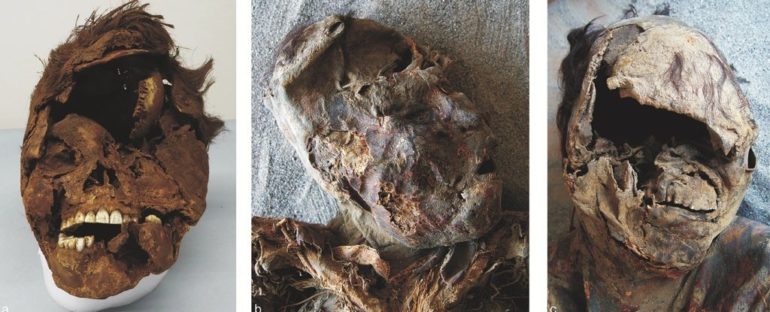

Marks of lethal trauma to the face. (Standen et al., JAA, 2021)

Far beyond the difficulty of growing crops in this extremely arid place, social tensions in a time of societal and cultural transformation led to dramatic confrontations and violence, the legacy of which can still be clearly seen on skeletons today.

“In this extreme desert, farming was dramatically restricted and confined to valley terraces, quebradas, and oases, with these pockets of land separated by extensive sterile interfluvial pampas that dominated the landscape,” researchers, led by first author and anthropologist Vivien Standen from the University of Tarapacá in Chile, write in their paper.

“Away from the fertile coast, moving out from these productive oases meant facing barren landscapes without water and resources for subsistence .. This new socio-cultural framework and land use could have triggered social tensions, conflict, and violence among groups investing in a horticultural lifestyle.”

To investigate, the researchers assessed the remains of 194 adult individuals buried in ancient cemeteries in the desert’s Azapa Valley, which was once one of richest and most fertile valleys in northern Chile.

Due to the extreme dryness of the desert environment, these skeletons are eerily well preserved, with some still featuring hair and soft tissue from approximately 800-600 BCE.

But in many of these ancient farmers, the signs of violence and fighting are unmistakable.

“Of the 194 adult individuals studied, 21 percent (n = 40) exhibited trauma compatible with interpersonal violence, regardless of the degree of completeness of the bodies,” the researchers explain.

“Of the total sample, 10 percent (20/194) showed perimortem [at or near the time of death] trauma, mostly with probable lethal consequences. Perimortem fractures in the cranium were observed in 14 individuals.”

According to the researchers, many of these high-impact trauma marks would have been caused by deliberate and intentional actions perpetrated by individuals in contexts of interpersonal violence – some of them killing blows, delivered either from a frontal confrontation, or an attack from behind.

“Some individuals exhibited severe high impact fractures of the cranium that caused massive destruction of the face and neurocranium, with cranio-facial disjunction and outflow of brain mass,” the researchers write, noting that injuries appear to have been caused by weapons such as maces, wooden sticks, batons, or arrowed projectiles.

As for why these bouts of violence ensued, the researchers think disputes over living spaces and resources like land and water were most likely, along with climatic events such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

“These factors could have triggered competition, tensions, and violent conflicts between competing neighboring social groups in the Azapa Valley during the Formative Period,” the team explains.

“Moreover, in this new economic mode based on land use and horticultural production, emergent leaders may have tried to hold greater scope of power and prestige by trying to control productive spaces, creating social inequalities within stressful conditions.”

The findings are reported in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.