The relentlessness of chronic pain wears you down. Beyond being a physical distraction in and of itself, it disrupts sleep, interferes with work and relationships, and can even alter the way we process emotions by causing physiological changes in our brains.

But the experience of long-term pain is complicated and varies between individuals, making it difficult to explain and quantify, let alone diagnose and manage.

Now, in a large study of over 21,500 people who visited the University of Pittsburgh’s severe pain management clinics, perioperative specialist Benedict Alter and colleagues have developed a new method to try to help work this out.

“We found that how a patient reports the bodily distribution of their chronic pain affects nearly all aspects of the pain experience, including what happens three months later,” the team wrote in their paper.

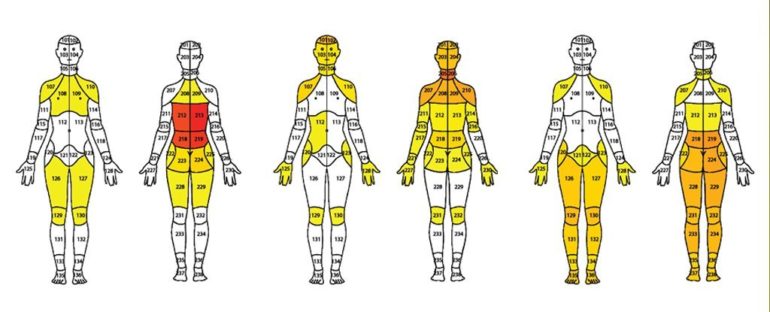

Using a computer clustering analysis of patient body pain maps and pain assessments, the researchers discovered that patients fit into nine groups of chronic pain, as defined in the image below.

What’s more, these patterns of pain distribution could predict pain intensity, pain quality, pain impact, physical function, mood, sleep and indicate likely patient outcomes.

(Alter et al., PLOS One, 2021)

Above: Body pain maps for each of the nine identified chronic pain clusters, with colored heat scale indicating frequency of pain.

For example, while the group of patients experiencing lower back pain radiating below the knee (group F) had worse physical function difficulties than those experiencing neck and shoulder pain (E) or neck, shoulder and lower back pain (G), these patients reported less anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance than the other two groups.

A subset of over 7,000 patients completed a follow-up questionnaire, three months after filling out the initial body pain map and questionnaire. Patients experiencing abdominal pain (group B) showed the most progress, with almost half reporting significant improvement.

Those with neck, shoulder and lower back pain (group G), however, demonstrated the worst outcomes on follow-up, with only 37 percent reporting improvements. This group shared characteristics with the two widespread pain groups, causing the team to ponder if this subgroup may be an early stage in developing generalized, widespread chronic pain. The researchers recommend a long term study to monitor pain duration and stability over time within this group.

What’s more, their findings that the more widespread the pain, the more persistent it is, are consistent with a recent MRI study in fibromyalgia patients that found the more widespread reported pain is on body maps, the more changes observed in brain connectivity around the pain-processing parts of the brain.

“A case can be made that reports of widespread pain collected with digital pain body maps are diagnostic of pathophysiological changes in pain processing,” Alter and team suggest.

This ability for body pain maps to indicate likely patient outcomes could help identify patients at risk of poor outcomes even from their first pain clinic visit.

Above: each row on the vertical axis represents an individual patient out of the entire cohort (N = 21,658 unique patients) organized by pain body map cluster membership.

With up to 40 percent of adults in the US currently experiencing chronic pain – which is likely to increase with the potential impacts of long term COVID-19 – diagnostic tools such as this could make a massive difference in many people’s lives.

There’s still a lot of work to do to untangle all these relationships, and the researchers caution that this is an observational study so they cannot establish causation.

“Outcome data do not address specific therapies, and therefore, it remains unclear which specific treatment may be helpful for a particular body map cluster,” they wrote.

However, Alter and team believe their study supports the idea that chronic pain is a disease process and these aspects of how its physical distribution manifests will be “important for future developments in diagnosis and personalized pain management”.

This research was published in PLOS One.