It’s the type of argument you’ve heard before, perhaps too many times, but not quite this way: The next generation of information and/or communications technology will support a new wave of productivity in the workplace. That wave will bring forth a new foundation for cost efficiency and commerce that benefits, directly or indirectly, everyone in the world’s broader economy. You would expect one of the major proponents of 5G Wireless to make such an argument. In recent weeks, one has: radio and network equipment major Nokia.

But no one needs to be reminded any more that we’re in a pandemic, the depths of which we may not have fully plumbed. So Nokia’s timing for publishing this argument may end up subjecting it to a level of scrutiny it might never have received back when the biggest problem on its agenda was Huawei.

As ZDNet’s Daphne Leprince-Ringuet first reported, Nokia’s Bell Labs — the jewel in the world’s research crown for 95 years running — predicted in an October report that business activity worldwide generated as a result of 5G adoption would add $8 trillion in activity to global gross domestic product (GDP) for the year 2030.

If you’ve ever been an editor, you hear the sirens going off in your head already. Nokia’s corporate press release stated, “5G-enabled industries have the potential to deliver $8trn in value to the global economy by 2030″ [emphasis ours]. A footnote explained Bell Labs reached this conclusion “based on aggregated regional forecasts of how wage growth, profitability growth and government revenue growth will be impacted by growing technology spend.” This is very tricky wording. Here, Nokia uses “spend” as a noun, not a verb, meaning “investment” as opposed to “expenditure” — two very different categories from an economist’s perspective. The former anticipates a return; the latter would just be a cost.

Stunningly, Nokia’s actual report is phrased differently. Under the heading “Potential value and growth,” the Bell Labs researchers wrote, “We expect the formulation of this economic equation — catalyzed through what we see as 5G+ enabled digitalization — will increase global GDP by $8 trillion in 2030” [emphasis theirs]. Not “by,” but “in,” which in this latter case implies that $8T in economic activity will have accumulated not over the next decade, but rather in a single year. As independent experts with whom ZDNet spoke have verified, the difference is night-and-day.

The productivity conundrum

“There was some confusing stuff in it,” remarked Dr. Sherman Robinson, senior research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute, referring to Nokia’s report, which he reviewed prior to his discussion with ZDNet. Dr. Robinson is also Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Sussex, and a frequent consultant to the World Bank.

“They said GDP will go up, and they basically looked at profits and wages, and government,” he explained. “That’s very confusing.”

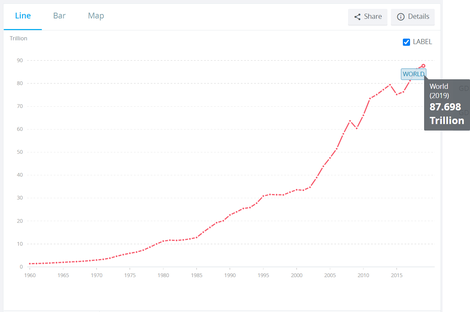

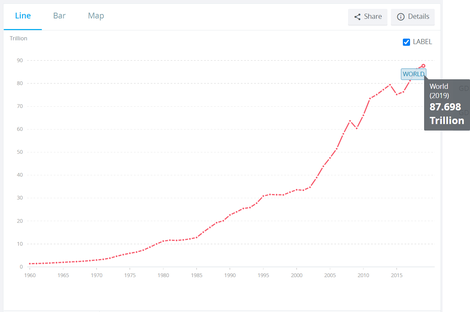

It’s a deceptive little curve: this seemingly exponential rise in global GDP, as depicted by data collected by the World Bank. The confusion brought about by Nokia’s report, Robinson believes, has to do with the correlation — or lack of it — between enterprise connectivity as a broad concept, and GDP as the product of an explicit formula. GDP is typically ascertained from either of two angles:

As an element of production, using GDP at factor cost, which accounts for payments made to capital and labor across all industries;From the final demand or expenditure side, which accounts for the value of (C) consumption goods; (I) investment goods such as construction, machinery, and tools; (G) government expenditures, which includes outlays for the Pentagon, as well as for the civil service; and (E) exports. Because the gross value of C, I, and G includes (M) imported goods, they’re subtracted from the total. The well-known formula is C + I + G + E – M.

Nokia provided ZDNet with a written explanation of its methodology, although we have not been permitted to reproduce it, since it’s currently being used for a subsequent report not yet published. In general, Nokia says its researchers studied the “gains” achieved in various industries, through their adoption of its 5G enterprise technology, as well as other methodologies that in turn make use of Nokia 5G. The company calls this superset of the 5G Wireless portfolio “5G+.”

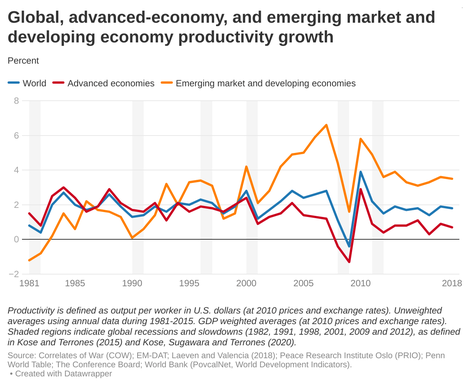

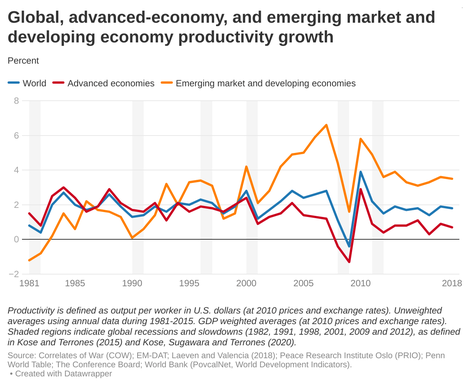

“We as a society have what we call a ‘productivity conundrum,'” remarked Fuad Siddiqui, speaking with ZDNet. Siddiqui is Nokia Bell Labs’ senior partner and vice president, and a principal contributor to the report. “Since the first and the second industrial revolutions, productivity growth rates have been declining from the 1950s onwards. In fact, you could argue that, from the third industrial revolution or the so-called ‘Internet Age,’ productivity growth rates have declined by almost one-third what they used to be over the [previous] 50 to 70 years.”

Publicly available economic data corroborates Siddiqui’s claim, particularly over the past four decades. As this productivity growth chart demonstrates, among advanced economies such as the US and Europe (the dark red line), although bouncing around like unwound yarn on a busy trampoline, the proximate trend line for this growth is slightly downward. It’s not that the global economy is contracting (although it’s expected to do so in 2020), but rather that the rate of growth is declining. Note here, however, that “productivity” is being measured per worker, as is typical, and not per industry or per business.

Nokia’s grand productivity claim is far from the first one attributed to 5G:

In November 2019, an IHS Markit study commissioned by Qualcomm projected $13.2 trillion in so-called “sales enablement” by 5G by 2035.Last February, a report produced by Pepperdine University Prof. James E. Prieger [PDF], presented to the US Federal Communications Commission, projected 5G development activity in US cities would collectively contribute a total of $907.29 billion to US GDP (note: not global GDP) between 2019 and 2025. In explaining his methodology, Prof. Prieger wrote, “These figures are best understood as the gains from 5G deployment and adoption,” adding that they also reflected an assumed reduction of costs by virtue of the elimination of “regulatory barriers.”In March, the Mobile Economy 2020 report produced by GSMA Intelligence projected, “5G technologies are expected to contribute $2.2 trillion to the global economy between 2024 and 2034.” In the same paragraph, the report stated that mobile technologies as a whole were already responsible for the generation of $4.1 trillion of so-called “economic value added” to 2019 global GDP.Then in April, an ABI Research report commissioned by Intel [PDF] projected that 5G coupled with artificial intelligence activity would be jointly responsible for 9.2 percent of global GDP in 2035. (Note the careful use of “by,” “between,” and “in” in the previous statements.)

Aggregation magic

Computers show up everywhere except in the productivity statistics.

— Robert Solow, Professor of Economics, MIT, 1987

The future value of 5G, as projected by the Nokia report as well as these four others, all rely on some factor over and above simple productivity attributable to 5G. Nokia’s report, however, may be the boldest of all. It assumes the presence of a world-changing transformation in the nature of business itself: one where industrial manufacturing of physical goods leap-frogs over the information technology production, to become the leading source of investment in communications technology, and thus in 5G.

This transformation, states the report, “will have two fundamental effects: Parity will be achieved between the ICT investment and GDP contribution of industries, and value creation will be catalyzed across industries and, ultimately, throughout the global economy.”

Siddiqui told us his research team studied the major industries that Nokia serves, seeking out the catalysts of productivity growth. In four industry categories — healthcare, communications, energy, and transportation — inter-sectoral growth starts to happen at some point in time, where the benefits from one sector spill over into others. Siddiqui attributes this sudden catalysis to an almost indeterminate force. “A number of physical network technologies came together,” he said, “fused to a certain point, and then created an aggregation magic.”

Unlike the first two industrial revolutions during what Siddiqui called the “Golden Century,” the third was focused on the consumer, and on the profits attainable through consumption as opposed to productivity. Said Siddiqui:

The data shows us that nations have hardly moved the needle in productivity growth. We put consumers in charge, and we ended up investing in our infrastructure, but all that supply-side investment was used primarily, predominantly for entertainment. And that hasn’t moved the needle. We have all these applications, and all these ways of distracting ourselves, but it’s hardly productivity-centric.

As we’ve discussed before, 5G’s initial business model depended upon a massive wave of revenue from updated consumer devices, to fund the tremendous infrastructure projects required to pave the planet with fiber. Now, Nokia’s research suggests telcos will need to look elsewhere — that consumers won’t be their initial source of capital. There’s a cultural issue here: a reliance upon disposable income that, in the COVID era, is becoming a scarce commodity.

There are a number of sociological variables that need to be considered, in addition to the economic ones. Clearly, the Nokia team is working to at least identify them, if not yet integrate them into their formula.

“We’ve seen examples of people having to do their schooling from home, on a wide scale, at a stage we’ve never been at before,” noted Dr. Sally Eaves, senior policy advisor for London-based Global Foundation for Cyber Studies and Research, and a contributor to the Nokia report. Speaking with ZDNet, Dr. Eaves continued:

We’ve had people sitting under bridges, because they can’t work from home and they haven’t got a connection. . . We have these digital equity gaps across the world, and I think, more broadly, not everybody’s been aware of them. One of the impacts of the COVID experience, that’s still continuing, is that it has laid those bare — things that were invisible are being made much more visible. It’s a travesty that we’ve got this, in this day and age. But sadly, it’s the case that there isn’t this democracy of access to technology. It’s not equal. And we’ve had lots of cases, whether it’s the UK or the US, where there’s the assumption that you’ve got an Apple that you can do your homework on, or an assumption that you’ve got a home Internet that works and is accessible to you. Unfortunately, that’s not always the case. We’ve got to have the foundational access level right across the world. We’ve got to have reliable data; we’ve got to have mobile signal. Everything else — when you talk about edge and AI, and all the other, different developments we’ve got in technology — if we haven’t got this underpinning foundation there, it excludes so many people from the opportunity it brings.

There is an argument to be made that inequity among workers has done more to dampen global economic growth, than any degree of inactivity or passiveness caused by the abundance of media.

“When COVID came, we realized that the supply infrastructure that we were building and the investments that we made, were able to pivot, in order to drive real, human, industrial needs,” said Fuad Siddiqui, offering the production of lifesaving equipment to hospitals, and the delivery of products directly to homes and businesses, as two examples. These examples serve to demonstrate, as he explained it, the conversion of digital industry to physical industry — the reinvestment of capital towards tasks that lend themselves more directly to measurable growth.

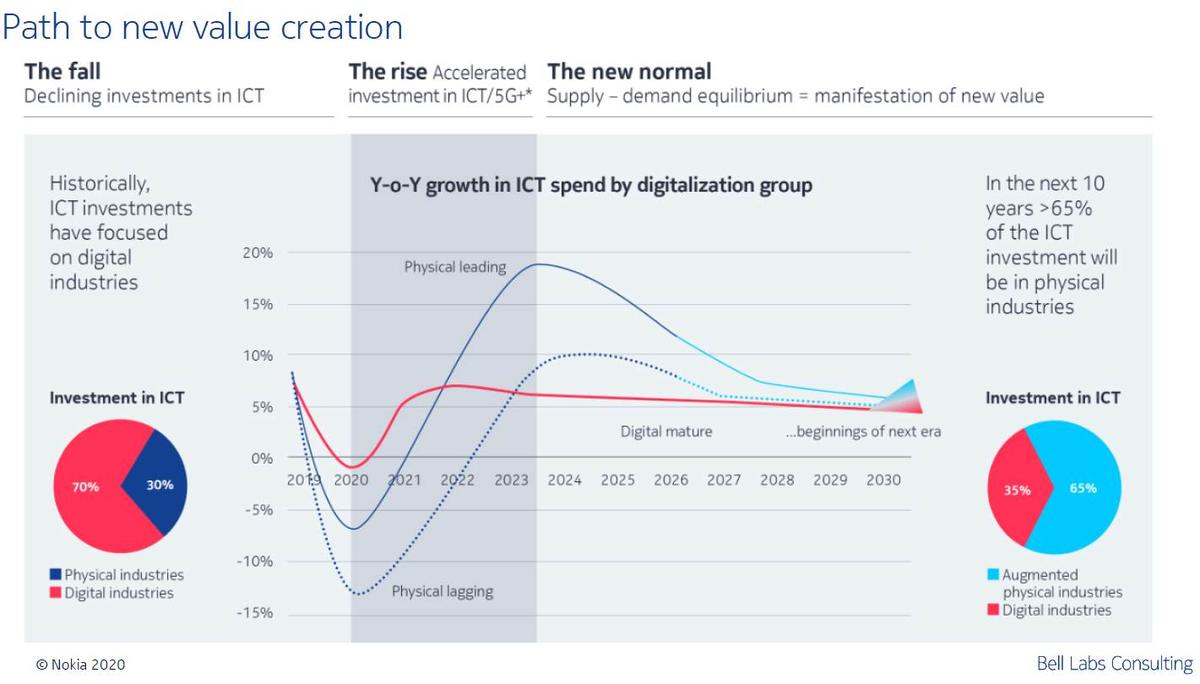

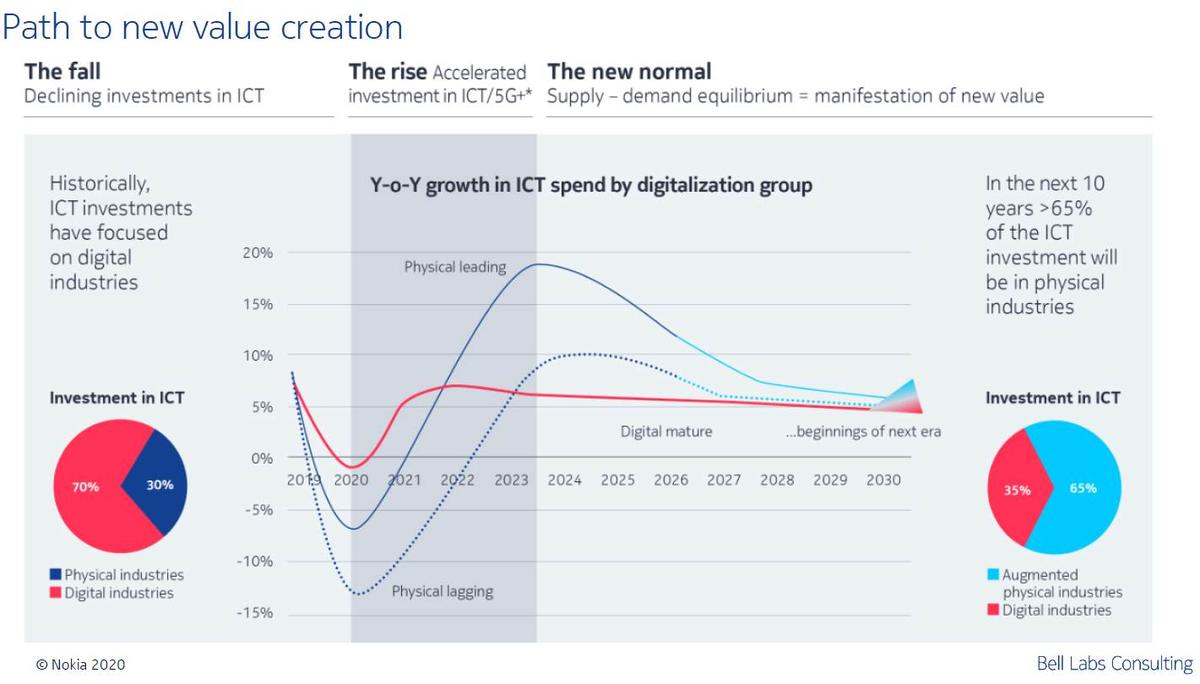

It’s this alchemical conversion that will be necessary, the Bell Labs team believes, for 5G to be able to contribute $8 trillion to the global economy, whether over time or in one lump sum. Siddiqui believes the current structure of established economies in the world, such as America’s, are weighted such that 70 percent of its ICT investments are directed to 30 percent of its industries. Throughout the coming decade, the Nokia report posits, the fusion phenomenon to which Siddiqui referred — the “aggregation magic” — may trigger a reversal, whereby some 65 percent of ICT investments become directed towards what Nokia calls “augmented physical industries.” Nokia defines this group as organizations whose business models have been transformed through the adoption of “end-to-end 5G technologies extensively in the next decade.”

How this ambiguous magic translates to an undisputed economic metric depends on layered waves of aggregation. He told ZDNet his researchers started with a baseline value they called enterprise ICT spend, based on multiple sources. Their goal was to obtain a 5G+ enablement factor, basing their forecast on a Bass diffusion model of 5G adoption across eight global regions. They chose one country to epitomize each region — for example, the US for North America, German for Western Europe, and South Africa for Africa.

The Nokia team then produced estimates of values for Safety, Productivity, Efficiency, and Resiliency (SPER), across 11 service sectors. The resulting variables were used to produce what’s being called the Bell Labs Consulting 5G+ Growth Model. This model does account for a decrease in overall investments by 11 percent during the pandemic period, but follows it up with a four-year recovery period beginning in 2021. During that period, Siddiqui believes, investments in physical business (again, as opposed to digital business) will be accelerated, finally leveling off by 2030.

As the 5G platform itself transitions to an as-a-service model, Nokia’s methodology continues, elements of the platform will become available a la carte, reducing procurement costs and contributing more to productivity numbers.

Nokia’s researchers observed how select industrial customers (their names, for now, being withheld) adopted early editions of its 5G stand-alone platform for enterprise customers. Looking at what Siddiqui termed “inputs” and “outputs,” the team calculated how the productivity gains from these customers contributed to their native countries’ productivity flow. “We used that,” he told us, “to then compute the resulting contribution to GDP.” That contribution is called the 5G+ GDP multiplier. Researchers applied that multiplier to estimate the contribution of all businesses in a chosen category as an aggregate.

In short, Nokia sampled select customer companies, estimated their productivity levels in the absence of 5G, took their productivity increases as coefficients, and applied those coefficients as factors to the rest of their industry. Then aggregated those industries for their respective countries, those countries for their global regions, and those regions for the world at large.

“Nothing is for sure. What we have laid out, with a lot of research, modeling, and real experiences,” said Siddiqui, “was the confluence of these factors to say, ‘This is a real opportunity ahead of us.’ If we join forces, and different stakeholders in the ecosystem come together, this is a real opportunity to transform our industries — those lagging and leading physical industries — which we’ve seen, in the first and second industrial revolutions, how they supercharged the economy.”

Causal inference

Is this the sort of tactic a serious macroeconomic study would typically do? More to the point, is this what these sorts of studies have really been doing all along: sampling individual instances, and applying their gains and losses to the rest of the economy as aggregates upon aggregates?

We asked someone who does this sort of thing as part of his job: Michael R. Ward, PhD., is a professor of economics at the University of Texas at Arlington. In 2014, Prof. Ward and Shilin Zheng of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences produced a wide-ranging examination of economic growth factors, including precisely the phenomenon Nokia Bell Labs has been working to observe, only in China, and as a function of history. They studied how mobile communications revolutionized the Chinese economy, both culturally and industrially.

Like the Bell Labs report, Ward and Zheng assume that the impact of telecommunications is a positive factor that may be expressed in a variable. Like Bell, Ward is wary that greater productivity gains may incite certain regions to adopt more liberal economic policies, thereby changing the variables used to ascertain growth in the first place — call it “digital transformation.” Plus, Ward realized that growth factors in one region may have ripple effects on another.

“We’ve got these technologies to try to estimate the productivity from these technologies,” Ward reminded ZDNet. “The problem with IT is that it changes so fast, that we don’t really get a long enough time series on it.”

An abundance of micro-economic studies over the last two decades, Ward told us, have examined industrial and financial activity at the plant level, ascertaining specific factors that may contribute to productivity. The challenge for economists and researchers is to do this at the macro level, particularly with a technology that could hang around for awhile before something else replaces it. IT infrastructure may be the best candidate — at least normally, since it’s often the last layer of IT to change. But telcos are already talking about 6G.

We asked Ward whether it would be feasible for an academic study to take the same approach that Bell Labs took: producing several levels of aggregates predicated upon sampling.

“It is, but you have to be very careful about this,” Ward responded. “You have to think about, what are the firms that are doing this now? They’ve got to be the cutting-edge firms. They’re probably using the best applications.”

A leading German auto maker, for instance, may be uniquely skilled at the art of adapting new technologies to its processes. As a result, it may be first to make such adaptations. But it may not be fair to apply that company’s productivity to all its German competitors — or, to go one step further, to the productivity profile of French auto makers.

“Applying this to another country, you probably have to scale it down some amount,” said Ward. “I don’t know what that amount is.”

What’s more: Historically, the first adopters of a technology enjoy the largest cost reductions. For those who follow along behind, not so much. So any multiplier researchers may be aiming for, should not be expressed as a constant.

Next, we asked Prof. Ward, when researchers study the impact of any phenomenon upon a country’s economy, how do they determine what GDP would have been, or would be, in the absence of that phenomenon? Ward responded:

This has been a big revolution in economics, and social science in general, in the last twenty years: what they call causal inference. We’re very susceptible to the criticism that correlation is not causation. So what we try to do is tease out these correlations that are most likely to be causally related. . . What we think we have found is a causal relationship between broadband and growth. If you believe that, then more broadband in the future should give you the same relationship with growth, as long as the future is similar enough to the past.

Ward and Zheng studied broadband penetration for each Chinese province. When one province had greater penetration than a neighbor, that neighbor was considered counterfactual — indicative of how circumstances might have been had broadband not been so pervasive. In a manner such as this, one can rationally extrapolate future growth trends for limited regions of the world, or certain industries in those regions, as the result of a measurable phenomenon. The following conditions must apply:

There must be a clear baseline against which to make a comparison, such as a region or industry less affected, if at all, by the same phenomenon;The dynamics of the compared regions should not differ very substantially from one another — for example, two neighboring districts in China, as opposed to Germany and Bulgaria;The methodology by which the “teasing” of the correlation is reached, can be explained as a function of math more than magic;The world to which these regions or industries belong are not significantly impacted by other, exogenous phenomena, such as pandemics, wildfires, trade wars, or other wars;The phenomenon being studied remains essentially the same from the beginning of the study period until the end — unlike 5G, whose cloudy nebulousness is only slightly masked by monikers like “5G+.”

Sherman Robinson’s experience with observing technology’s impact on the economy dates back to the 1960s. He told ZDNet:

I was at the Congressional Budget Office when people were trying to figure out, “How do we measure the contribution of computers to GDP? Do we figure out if they’re more productive? Do we figure out some index of higher productivity?” My boss at the time said, “Well, wait a minute. Moore’s Law is at work, and the machine is much faster, but it doesn’t speed up how fast my secretary types a letter.” If you’re just taking something like Moore’s Law and applying it to economic data, that’s wrong. It has to make people more productive.

When the economy is performing well, we can safely place our hopes and dreams on cruise control, thinking more about our goals than the means, more about the destination than the journey. Eight trillion dollars’ worth of extra economic activity sounds like a well-earned dessert. When that same economy comes under physical attack by an unseen invader, suddenly each step along our route matters, and our anxiety about tripping ourselves up along the way, rises. We pay closer attention to how we choose the directions we take.

Or perhaps that, too, is an aspirational goalpost.

Learn more — From CNET Networks

Elsewhere

The Impact of 5G: Creating New Value across Industries and Society [PDF] by Rodrigo Arias, Isabelle Mauro, et al, World Economic Forum