Predictive policing has been shown to be an ineffective and biased policing tool. Yet, the Department of Justice has been funding the crime surveillance and analysis technology for years and continues to do so despite criticism from researchers, privacy advocates and members of Congress.

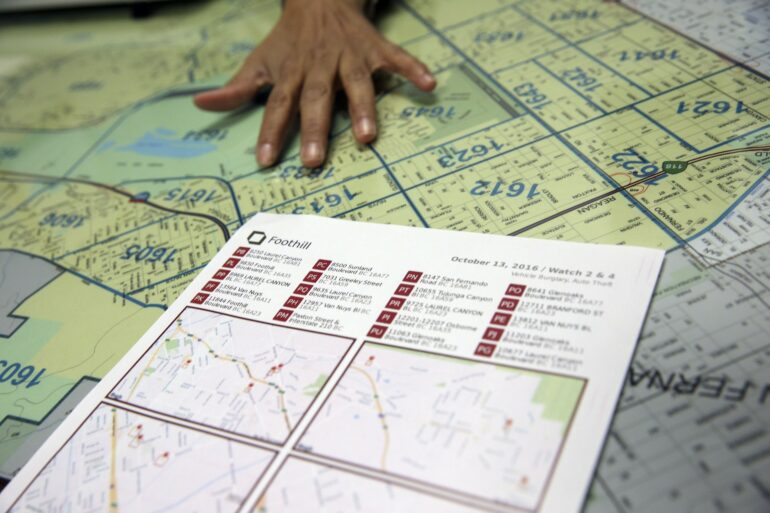

Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., and U.S. Rep. Yvette Clarke, D-N.Y., joined by five Democratic senators, called on Attorney General Merrick Garland to halt funding for predictive policing technologies in a letter issued Jan. 29, 2024. Predictive policing involves analyzing crime data in an attempt to identify where and when crimes are likely to occur and who is likely to commit them.

The request came months after the Department of Justice failed to answer basic questions about how predictive policing funds were being used and who was being harmed by arguably racially discriminatory algorithms that have never been proven to work as intended. The Department of Justice did not have answers to who was using the technology, how it was being evaluated and which communities were affected.

While focused on predictive policing, the senators’ demand raises what I, a law professor who studies big data surveillance, see as a bigger issue: What is the Department of Justice’s role in funding new surveillance technologies? The answer is surprising and reveals an entire ecosystem of how technology companies, police departments and academics benefit from the flow of federal dollars.

The money pipeline

The National Institute of Justice, the DOJ’s research, development and evaluation arm, regularly provides seed money for grants and pilot projects to test out ideas like predictive policing. It was a National Institute of Justice grant that funded the first predictive policing conference in 2009 that launched the idea that past crime data could be run through an algorithm to predict future criminal risk. The institute has given US$10 million dollars to predictive policing projects since 2009.

Because there was grant money available to test out new theories, academics and startup companies could afford to invest in new ideas. Predictive policing was just an academic theory until there was cash to start testing it in various police departments. Suddenly, companies launched with the financial security that federal grants could pay their early bills.

National Institute of Justice-funded research often turns into for-profit companies. Police departments also benefit from getting money to buy the new technology without having to dip into their local budgets. This dynamic is one of the hidden drivers of police technology.

How predictive policing works – and the harm it can cause.

Once a new technology gets big enough, another DOJ entity, the Bureau of Justice Assistance, funds projects with direct financial grants. The bureau funded police departments to test one of the biggest place-based predictive…