For years, ARM has been agitating the market to place its architecture in an increasing proportion of data center sales, and it has had some success. But the incumbent — primarily Intel, but x86 in general — has remained entrenched for a variety of reasons.

Now, however, shifts in markets, technologies and business alliances are changing the equation. The market shift is primarily about who does the buying. In the past, big server installations were predominantly located in large enterprises, companies with lots of employees, businesses and data.

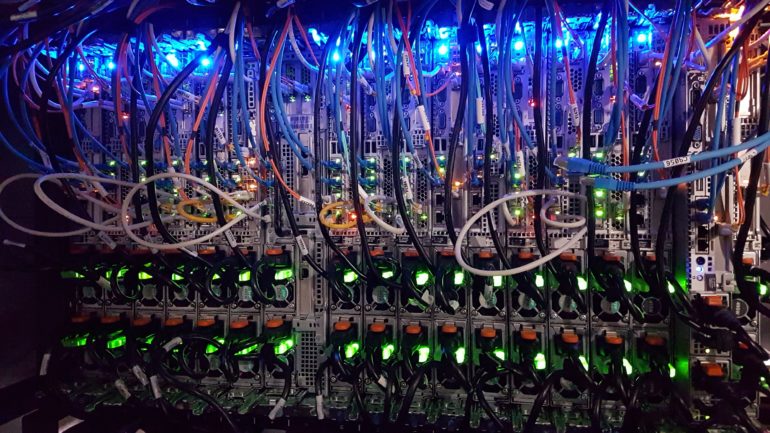

Recently, much new server capacity has come from cloud-service providers, which are effectively mega enterprises — in fact, whole ecosystems — by themselves. This development has shifted power toward the buyers because there are fewer of them, they are more powerful and more particular. They like to do things their way and can afford to experiment within their own environments without disturbing production. Thus, Amazon is able to design its own processor around an ARM core.

Technological Evolution

The technology shift comes along a similar path as Moore’s Law; that is, process nodes continue to shrink, and greater capability takes less power and space than before. The knock-on ARM in servers has always been raw performance. Essentially, Intel made the case that certain applications required as much of it as they could get nearly without regard to cost or power consumption. But that argument finally began to run into the law of large numbers. Meanwhile, ARM’s raw performance, its weakest suit, has improved, boosted by the fact that ARM’s customers’ main foundries (TSMC and Samsung) are now leading the pack in process-node development.

In addition, parallelism has created performance improvements along another dimension. In applications that benefit from parallel algorithms, graphics processing chips and specialty chips such as FPGAs have been able to take over some of the computing load in large cloud installations. Finally, as artificial intelligence becomes a feature of an increasing number of computing installations, specialty chips with a high degree of parallelism and lower precision are finding their way into new cloud environments. All of these developments favor challengers and challenge incumbents.

Changing Business Alliances

Then there are business alliances. At this moment, market-leading GPU (graphics processing unit) maker Nvidia is planning to acquire ARM. It’s already clear that the cloud service providers want the kind of highly parallel, low-power, high-performing chips now at the top of ARM’s line.

Nvidia has crafted a complete scalable server solution with CPU, GPU, DSP and interconnect technology. With a reasonable chance that the deal will go through, ARM could leverage Nvidia’s investment to fill in the missing pieces — primarily tools, templates, reference designs, languages, compilers and other elements — that make up a complete ecosystem on which partners could rely.

Nvidia, already a deep ARM licensee, has the capital ARM needs to fully address the server market. Such a combination would open up competition greatly in the server market.

The Nature of the Deal

Intel isn’t the only firm wary of the Nvidia-ARM deal. Fundamentally, ARM’s licensees fall into two categories: core licensees, who pretty much work with whatever ARM has on the shelf; and architectural licensees, who have the right to modify ARM’s designs to their hearts’ content. There are only a handful of architectural licensees, particularly for the 64-bit designs appropriate for servers. Nvidia is one. Known others include AMD, Apple, Applied Micro, Broadcom, Cavium, Huawei, Qualcomm and Samsung.

For various reasons, many of these companies believe they have something to lose if a key industry asset (ARM) changes ownership from an arguably neutral party (Softbank) to a highly interested one (Nvidia). The other architectural licensees fear that Nvidia would use its privileged position to outflank them in the marketplace.

For example, Nvidia could study the specifications for new ARM products thoroughly before releasing them to competitors, thus getting a jump on the product development cycle. Nvidia could even push ARM’s development plans in a direction favorable to itself without regard to the interests of its competitors.

While these fears are natural, they may not be entirely rational. Although Nvidia might appear indifferent to the fate of its competitors, it does have its interests at heart on a number of fronts. If Nvidia is able to complete the acquisition of ARM, it would want to maintain — and even grow — the subsidiary’s businesses. For that reason, it would tend to be accommodating toward ARM’s current customers.

In addition, Nvidia’s competitors have actual contracts with ARM, documents of legal force that specify what their rights and obligations are. Nvidia would be foolish to try to abrogate these arrangements. The company has said publicly that it has no intention to change ARM’s business model.

The key to the ARM-Nvidia relationship is that together they hope to offer a viable, large-scale alternative to the current x86 regime in servers. Nvidia expects to help ARM get to market products on its roadmap that are currently languishing for want of investment.

Notes on Prominent Architectural Licensees

Apple takes ARM’s basic design, goes behind its garden wall, and works in secret to produce its own highly customized processors. It’s a good piece of business for ARM, and there’s no reason for Nvidia to disturb this relationship.

Huawei has been enjoying its “most-favored-nation” status as ARM’s largest server-processor licensee. Under an Nvidia regime, it would likely lose this pole position, but there are hundreds of other firms behind Huawei that would get a better deal than they are enjoying now. ARM has been somewhat inconsistent in applying its policies to customers, anointing some and making them “more equal than others.” Nvidia has said it expects to treat classes of licensees the same.

This issue would also affect Qualcomm, which is currently “most favored” in mobile processors. In addition, Qualcomm recently bought NUVIA, a chip design company, to help with future data-center processors. Qualcomm may see the ARM-Nvidia deal as a threat to this investment.

Nonetheless, Nvidia can’t go it alone in servers. Intel has dozens, if not hundreds, of server processors. Without a wide array of willing partners, Nvidia and ARM would be unable to cover every workload. If the company mistreats ARM’s licensees, it would have no incentive to build all the different types of server processors the consortium is going to need to compete effectively with x86.

Nvidia needs their trust. It’s key to ARM’s success.