It’s an eye-catching statistic: 58% of the whole population and 75% of kids in the U.S. had been infected by the coronavirus by the end of February 2022. That’s a pretty big jump from the official case count that hovered around a quarter of Americans having been diagnosed with COVID-19. A report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention based these higher proportions on what’s called a serosurvey: a study that looks at people’s blood to see if they’ve had a particular illness.

Isobel Routledge is an infectious disease epidemiologist who uses serosurveys in her own research. Here she explains the science behind the approach and what a serosurvey can – and can’t – tell you.

What does a serosurvey look for?

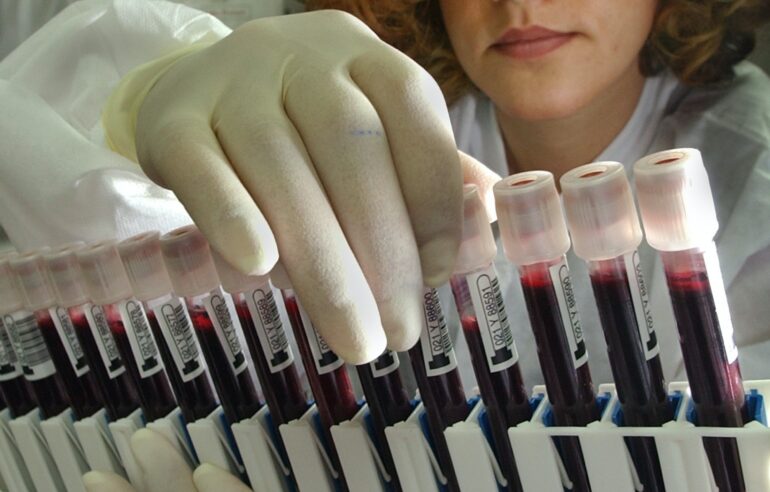

When you’re infected by or vaccinated against a pathogen, like the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19, your body produces antibodies to fight it. Some types of antibodies remain in your blood long after you’ve recovered. During a serosurvey, researchers look in blood samples for these long-lasting antibodies. They act as markers of past exposure to the pathogen.

The power of this type of study is that it can reveal whether someone was previously infected with a particular pathogen, even if they didn’t have symptoms or take a test. Having specific antibodies in your blood can also mean you’re immune to a certain disease – scientists are still investigating what the markers of protection against COVID-19 might be, though.

If they test enough blood samples – ideally through a random sample of the population – researchers can use a serosurvey to estimate the proportion of a population that has been previously infected or vaccinated, and in some cases estimate the proportion of the population that is immune to a particular disease.

Researchers can focus on specific antibodies that your body makes after catching COVID-19 that are different from the ones triggered by vaccination.

Scott Heins/Getty Images

Can serosurveys tell the difference between an infection and vaccination?

Yes. In a recent study, my colleagues and I wanted to separate out those who had been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 and those who had been vaccinated. So we looked for two different bio-markers in the blood samples.

Vaccines administered in the U.S. trigger your body to produce antibodies to a particular part of the SARS-CoV-2 virus called the spike protein. If we identified antibodies to the spike protein, that means a person could have been vaccinated, been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2, or both.

When people are naturally infected with SARS-CoV-2, they produce antibodies to another part of the coronavirus called the nucleocapsid protein. If we identified antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein, then we knew the patient had previously contracted COVID-19. Vaccination doesn’t trigger these particular antibodies. The CDC study used this type of test to separate out…