Almost nothing in the world is still. Toddlers dash across the living room. Cars zip across the street. Motion is one of the most important features in the environment; the ability to predict the movement of objects in the world is often directly related to survival – whether it’s a gazelle detecting the slow creep of a lion or a driver merging across four lanes of traffic.

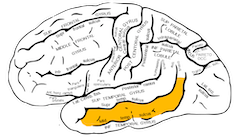

Motion is so important that the primate brain evolved a dedicated system for processing visual movement, known as the middle temporal cortex, over 50 million years ago. This region of the brain contains neurons specialized for detecting moving objects. These motion detectors compute the information needed to track objects as they continuously change their location over time, then sends signals about the moving world to other regions of the brain, such as those involved in planning muscle movements.

The middle temporal cortex is involved in processing visual movement.

Gray, vectorized by Mysid, colored by was_a_bee/Wikimedia Commons

It’s easy to assume that you see and hear motion in a similar way. However, exactly how the brain processes auditory motion has been an open scientific question for at least 30 years. This debate centers on two ideas: One supports the existence of specialized auditory motion detectors similar to those found in visual motion, and the other suggests that people hear object motion as discrete snapshots.

As computational neuroscientists, we became curious when we noticed a blind woman confidently crossing a busy intersection. Our laboratory has spent the past 20 years examining where auditory motion is represented in the brains of blind individuals.

For sighted people, crossing a busy street based on hearing alone is an impossible task, because their brains are used to relying on vision to understand where things are. As anyone who has tried to find a beeping cellphone that’s fallen behind the sofa knows, sighted people have a very limited ability to pinpoint the location or movement of objects based on auditory information.

Yet people who become blind are able to make sense of the moving world using only sound. How do people hear motion, and how is this changed by being blind?

People who are blind are better able to track auditory motion in noisy conditions compared with sighted people.

Orbon Alija/E+ via Getty Images

Crossing a busy street by sound alone

In our recently published study in the journal PNAS, we tackled the question of how blind people hear motion by asking a slightly different version of it: Are blind people better at perceiving auditory motion? And if so, why?

To answer this question, we used a simple task where we asked study participants to judge the direction of a sound that moved left or right. This moving sound was embedded in bursts of stationary background noise resembling radio static that were randomly positioned in space and…