The island prefecture of Hokkaidō, Japan’s second-largest island, has a rich cultural history of hunter-gatherers both on land and at sea. Over thousands of years through the Holocene and into the 19th century, the prevalence of these cultures across the island waxed and waned. Climate oscillations and changing seas were likely important factors in these cultural shifts, a new study shows.

Historically, Hokkaidō was home to two main types of subsistence cultures: land-based hunter-gatherers, such as the Zoku-Jomon and Satsumon peoples, and seafarers like the Okhotsk people. The Zoku-Jomon and Satsumon peoples gathered and likely managed millet, barley, and beans, whereas the Okhotsk primarily fished, hunted for marine mammals such as seals, and collected other marine foods. Each group is ancestral to the contemporary Ainu people.

Historical records and archaeological evidence of these three cultures span thousands of years, from 8,000 years before the present to the late 19th century, when modern lifestyles began to replace hunter-gatherer culture. Historians and scientists thought shifts in which cultures were dominant and where they were located could be related to climate, but evidence to robustly connect the dots was lacking.

In search of an answer, paleoclimatologists Masanobu Yamamoto and Osamu Seki, both of Hokkaidō University in Japan, turned to a bog on Rishiri Island, north of Hokkaidō, to test whether its deep peat deposits could hold clues to past climates. With students in tow, the two researchers extracted 5-meter bog cores comprising mostly peat moss commonly found in subpolar bogs worldwide. The researchers carbon-dated the core and analyzed the oxygen isotopic composition of cellulose in the peat moss and grasses as oxygen isotopes in plants are related to climatic factors like precipitation, humidity, and water source.

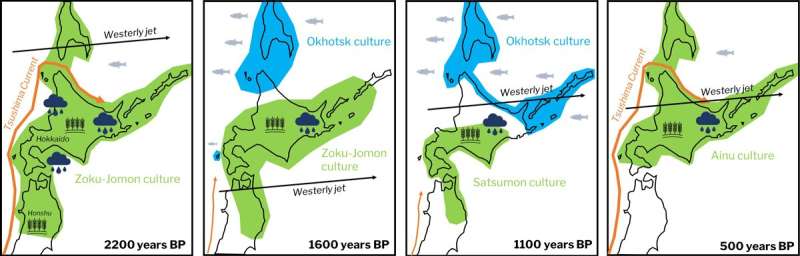

As currents and climates changed over thousands of years, Japan’s subsistence cultures responded, shifting where they were centered and how widespread they were. © M. Yamamoto and AGU

The authors used oscillations in the cellulose’s oxygen isotopes to reconstruct 4,400 years of the position of the summer westerly winds, which influences the summer monsoon, and a regional ocean current called the Tsushima Warm Current, which delivers warm, moist air to the region. They discovered a large shift in oxygen isotopes about 2,300 years ago, suggesting a switch in north Hokkaidō’s climate from being controlled mostly by the westerlies and monsoon to being controlled by the Tsushima Warm Current.

Changes in the location of the sea-dependent Okhotsk culture correlated with the strength of the Tsushima Warm Current, which cut off nutrients that spurred growth throughout the food chain. As the climatic controls shifted, so too did cultures in Hokkaidō—from around 1,600 years ago to 1,100 years ago, marine Okhotsk culture expanded when the Tsushima Warm Current weakened. But as the Tsushima Warm Current strengthened and nutrients dwindled, inland cultures thrived and expanded.

The inland Zoku-Jomon and Satsumon cultures were more responsive to the summer westerlies and the monsoon season. When the westerlies moved northward, warm and wet summers persisted.

“Most people think climate change affects human societies, but we still don’t know well the mechanisms and processes of how this happens,” Yamamoto said. “I think this [study] is a very important step for our field.” Examining cultures like these, with strong, direct ties to their environment and climate, is a helpful way to learn how different societies respond to climate change, he added.

The study appears in Geophysical Research Letters.

More information:

Masanobu Yamamoto et al, Impact of Climate Change on Hunter‐Fisher‐Gatherer Cultures in Northern Japan Over the Past 4,400 Years, Geophysical Research Letters (2022). DOI: 10.1029/2021GL096611

Provided by

American Geophysical Union

This story is republished courtesy of Eos, hosted by the American Geophysical Union. Read the original story here.

Citation:

Climate and currents shaped Japan’s hunter-gatherer cultures (2022, May 6)