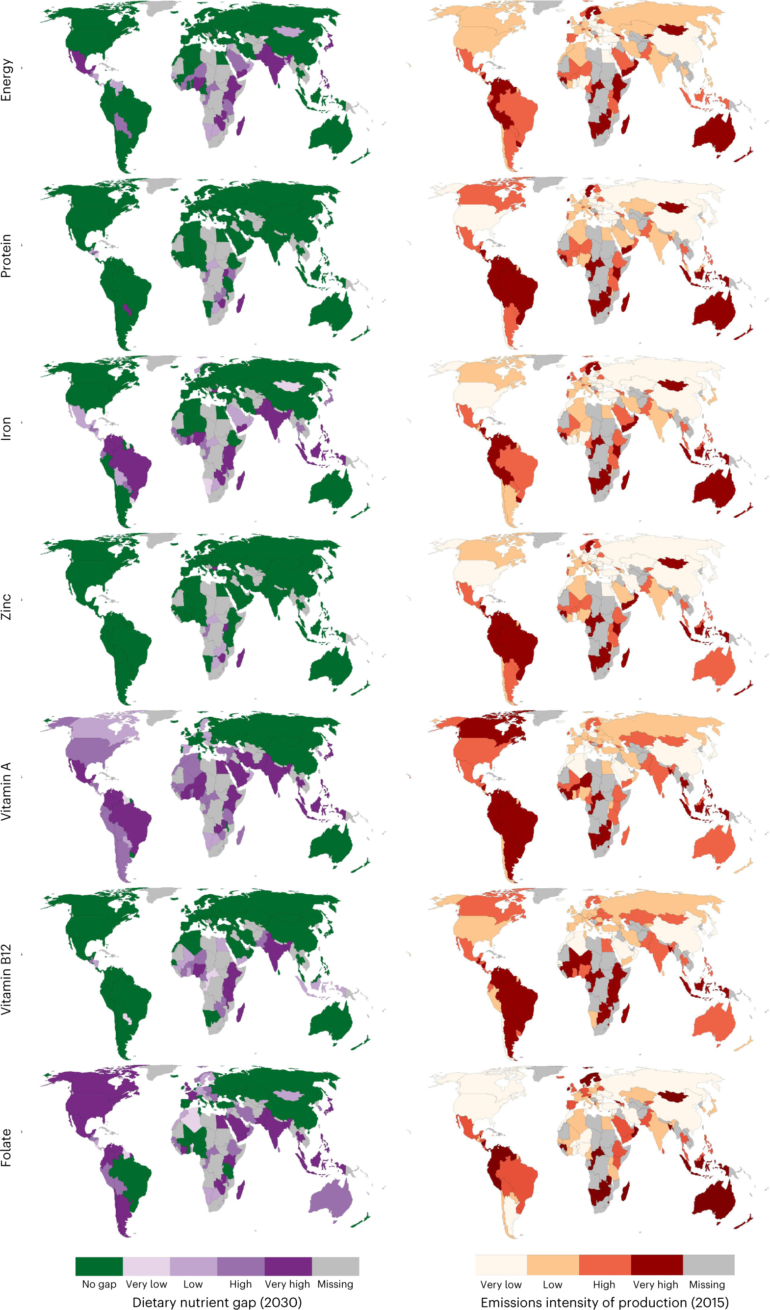

How do we tackle world hunger, hidden hunger and climate change? It’s possible to address both world hunger and hidden hunger while reducing agricultural greenhouse emissions at the same time. And we can do it without having to double food production or radically changing our diets to keep up with a growing global population.

These are the surprising findings from a new study by researchers from Deakin University’s School of Life and Environmental Sciences, published in the journal Nature Food.

How could it work?

“We can address hunger—that’s insufficient caloric intake—and hidden hunger—vitamin and/or mineral deficiency—for a growing global population in 2030 and still comply with the greenhouse gas emissions budget required under the Paris Agreement,” says postdoctoral researcher Özge Geyik.

Dr. Geyik, Dr. Michalis Hadjikakou, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Science, and Professor Brett Bryan, Alfred Deakin Professor of Global Change, Environment, and Society, used a method called linear programming to minimize greenhouse gas emissions while meeting the nutritional requirements of the world in 2030 under several intervention scenarios related to agricultural productivity, food loss and waste, and international trade.

This approach led to “optimal food baskets,” as Dr. Geyik puts it, containing the climate-friendly and nutritious food sources that the world needs to produce more of.

What’s in those baskets?

According to the findings, the foods that provide the required nutrients with the least emissions possible are vegetables, orange or red-fleshed roots and tubers, fruits and eggs.

And, while increasing the global production of cereals has helped reduce world hunger, while causing environmental damage at the same time, Dr. Geyik believes we may no longer need to prioritize the production of more cereals.

“What we need, instead, is to produce larger quantities of vegetables, roots and tubers, fruits and eggs, depending on what’s missing in the current food supplies. And that means we may not need to embrace radical dietary changes that may be culturally less acceptable, such as removing animal products altogether, to meet climate targets,” she says.

Radical dietary change: It’s not always the answer

There’s a growing interest in sustainable food systems amongst researchers, United Nations agencies, international non-government organizations (NGOs) and the public. Some research and advocacy groups have suggested wholesale dietary shifts, such as flexitarian, vegetarian, or vegan diets, as the answer.

Dr. Geyik argues this may not necessarily be the case, especially when it comes to addressing hunger and hidden hunger.

“Radical change in human diets—that have been shaped over millennia—may be incompatible with the urgency of addressing zero hunger and climate action in parallel,” she says.

“Our findings offer alternative transition pathways to sustainable food systems, ones with a focus on food as an essential need and an indispensable part of cultures. They show that we need to be multitasking along the way and address agricultural productivity and food loss and waste at the same time as developing innovative policies targeted towards sustainable nutrition.

“Policy and research efforts need to prioritize producing the foods that can provide missing nutrients with the least greenhouse gas emissions possible to complement efforts for improving agricultural productivity and reducing food loss and waste.”

Dr. Geyik says, “It’s win-win for both the environment and the growing world population.”

Key findings:

We could easily comply with the Paris Agreement if food production and trade policies prioritize foods that provide nutrients with the least emissions and then combine this with agricultural productivity improvements and reducing food loss and wasteOur plates need to look different than they do today. Global production of cereals has doubled between 1990–2020. While this helped eradicate hunger, we need to shift the focus away from micronutrient-poor cereals. What we need, instead, is to produce larger quantities of fruits and vegetablesWe may not need to embrace radical dietary changes that may be culturally less acceptable, such as removing animal products altogether, to meet climate targetsWe don’t need to double food production to keep up with a growing global population

More information:

Özge Geyik et al, Climate-friendly and nutrition-sensitive interventions can close the global dietary nutrient gap while reducing GHG emissions, Nature Food (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s43016-022-00648-y

Citation:

Climate-friendly, nutrition-sensitive interventions could close the global dietary nutrient gap while reducing emissions (2023, March 10)