Geography textbooks describe the Earth’s mantle beneath its plates as a well-mixed viscous rock that moves along with those plates like a conveyor belt. But that idea, first set out some 100 years ago, is surprisingly difficult to prove. A mysterious find on Easter Island, investigated by Cuban, Colombian and Utrecht geologists among others, suggests that the Earth’s mantle seems to behave quite differently.

Easter Island consists of several extinct volcanoes. The oldest lava deposits formed some 2.5 million years ago on top of an oceanic plate not much older than the volcanoes themselves. In 2019, a team of Cuban and Colombian geologists left for Easter Island to accurately date the volcanic island.

To do so, they resorted to a tried-and-tested recipe: dating zircon minerals. When magma cools, these minerals crystallize. They contain a bit of uranium, which “turns” into lead through radioactive decay. Their findings are available as a preprint in ESS Open Archive.

Because we know how fast that process happens, we can measure how long ago those minerals formed. The team from Colombia’s Universidad de Los Andes, led by Cuban geologist Yamirka Rojas-Agramonte, therefore went in search of those minerals. Rojas-Agramonte, now at the Christian Albrechts-University Kiel, found hundreds of them. But surprisingly, not only from 2.5 million years old, but also from much further back in time, up to 165 million years ago. How could that be?

Chemical analysis of the zircons showed that their composition was more or less the same in all cases. So, they all had to have come from magma of the same composition as that of today’s volcanoes. Yet those volcanoes cannot have been active for 165 million years, because the plate below them is not even that old. The only explanation then is that the ancient minerals originated at the source of volcanism, in the Earth’s mantle beneath the plate, long before the formation of today’s volcanoes. But that presented the team with yet another conundrum.

Hotspot volcanoes and their origins

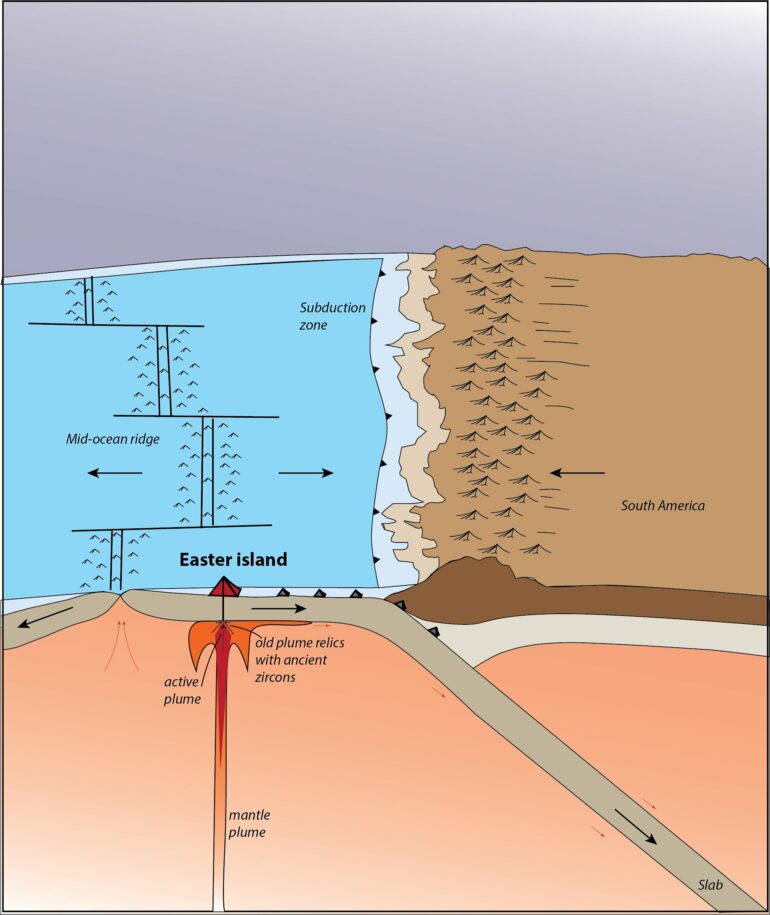

Volcanoes like those on Easter Island are so-called “hotspot volcanoes.” These are common in the Pacific Ocean; Hawai’i is a famous example. They form from large blobs of rock that slowly rise from the deep Earth’s mantle—so-called mantle plumes. When they get close to the base of the Earth’s plates, the rocks of the plume as well as from the surrounding mantle melt and form volcanoes.

Scientists have known since the 1960s that mantle plumes stay in place for a very long time while the Earth’s plates move over them. Every time the plate shifts a bit, the mantle plume produces a new volcano. This explains the rows of extinct underwater volcanoes in the Pacific Ocean, with one or a few active ones at the end. Had the team found evidence that the mantle plume under Easter Island has been active for 165 million years?

Statues on Easter Island. © Douwe van Hinsbergen

Subduction zones

To answer that question, Rojas-Agramonte needed evidence from the geology of the “Ring of Fire,” an area around the ocean with many earthquakes and volcanism, where oceanic plates dip (“subduct”) into the Earth’s mantle. So she contacted Utrecht geologist Douwe van Hinsbergen.

“The difficulty is that the plates from 165 million years ago have long since disappeared in those subduction zones,” says Van Hinsbergen, who had reconstructed the vanished pieces in detail. When he added a large volcanic plateau to those reconstructions at the site of present-day Easter Island 165 million years ago, it turned out that that plateau must have disappeared under the Antarctic Peninsula some 110 million years ago.

“And that just so happened to coincide with a poorly understood phase of mountain building and crust deformation in that exact spot. That mountain range, whose traces are still clearly visible, could well be the effect of subduction of a volcanic plateau that formed 165 million years ago,” he adds.

His reconstruction therefore showed that the Easter Island mantle plume could very well have been active for that long. This would solve the geological mystery of Easter Island: the ancient zircon minerals would be remnants of earlier magmas that were brought to the surface from deep inside the earth, along with younger magmas in volcanic eruptions.

Inconsistencies

But then another problem presents itself. The classical “conveyor belt theory” was already difficult to reconcile with the observation that mantle plumes stay in place while everything around them continues to move. Van Hinsbergen says, “People explained this by saying that plumes rise so fast that they are not affected by a mantle that was moving with the plates. And that new plume material is constantly being supplied under the plate to form new volcanoes.”

But in that case, old bits of the plume, with the old zircons, should have been carried off by those mantle currents, away from the location of Easter Island, and could not now be there at the surface.

“From that, we draw the conclusion that those ancient minerals could have been preserved only if the mantle surrounding the plume is basically as stationary as the plume itself,” he adds.

The discovery of the ancient minerals on Easter Island therefore suggests that the Earth’s mantle behaves fundamentally differently and moves much slower than has always been assumed; a possibility that both Rojas-Agramonte and Van Hinsbergen and their teams raised a few years ago in studies on the Galapagos Islands and New Guinea, and for which Easter Island now provides new clues.

More information:

Yamirka Rojas-Agramonte et al, Zircon xenocrysts from Easter Island (Rapa Nui) reveal hotspot activity since the middle Jurassic, ESS Open Archive (2023). DOI: 10.22541/au.170129661.17646127/v1

Provided by

Utrecht University

Citation:

Easter Island’s volcanic history suggests Earth’s mantle behaves quite differently than previously assumed (2024, October 16)