The ocean has a major influence on weather and climate. Scientists estimate it has absorbed more than 90% of the heat and 25% of the excess carbon released into the atmosphere by human activities.

As the climate crisis grows more dire, it is increasingly urgent that we understand the exchange of carbon between the atmosphere and the ocean, particularly over the Southern Ocean, where we believe nearly half of the carbon uptake occurs.

MBARI scientists from the Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observations and Modeling (SOCCOM) project—in collaboration with the National Center of Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and a team of researchers from Université du Québec à Montréal, NOAA, the Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observatory, and the University of Arizona—used data from a network of biogeochemical profiling floats to provide vital information about how storms affect the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide.

The team shared their findings in a recent research publication in the journal npj Climate and Atmospheric Science. Their work will allow researchers to better model future changes to the ocean and our climate.

“The Southern Ocean plays an important role in Earth’s climate. This remote region absorbs a great amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. As the climate crisis worsens, we need to understand just how much carbon the Southern Ocean absorbs.

“By using data from profiling floats, we’ve learned that storms tip the scales in the air–sea exchange of carbon in the Southern Ocean, triggering the release of carbon,” said MBARI Research Associate Magdalena Carranza, lead author of the study.

The atmosphere and the ocean are closely linked. At the ocean’s surface, carbon dioxide ebbs and flows between the atmosphere and the depths below. Carbon dioxide in the ocean goes through a variety of transformations by chemical reaction or the biology of marine life, and moves around with oceanic circulation and turbulence.

Under some conditions, carbon dioxide may also be released back into the atmosphere, a process known as outgassing. Understanding how carbon flows between the ocean and atmosphere is critical to modeling the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon and predict the impacts of climate change in the future.

The ocean and the microorganisms that live in it are our unsung allies in fighting climate change. Over the industrial era, the ocean has absorbed more than 25% of carbon dioxide emitted by human actions, buffering us from the impacts of climate change. Historically, the Southern Ocean—the frigid waters surrounding Antarctica—has been considered a major sink for carbon dioxide.

Because of the harsh environment of the Southern Ocean, traditional measurements of ocean conditions made from ships are few and far between. Ships also avoid storms, and therefore omit recording their influence.

Modeling studies, however, suggest that this remote region plays an important role in the planet’s carbon and climate cycles. Climate models suggest that the Southern Ocean accounts for roughly 40% of all oceanic uptake of carbon dioxide generated by humans.

The SOCCOM project launched in 2014 to deploy an array of robotic floats and advanced chemical sensors in the Southern Ocean. Housed at Princeton University, SOCCOM is a multi-institutional program focused on unlocking the mysteries of the Southern Ocean and determining its influence on climate.

The cutting-edge biogeochemical observations and modeling carried out under the SOCCOM project will help researchers better understand the inner workings of the Southern Ocean and how it impacts Earth’s climate.

SOCCOM’s network of profiling floats are continuously logging data about the Southern Ocean. Biogeochemical (BGC) Argo floats traverse the water column, gathering important observations every 10 days under all weather conditions, including beneath storms.

Critically, the BGC Argo floats can measure the acidity of the ocean using a pH sensor developed by MBARI scientists. By measuring ocean acidity, researchers can estimate the ocean’s carbon content and infer air–sea carbon dioxide exchange.

Recent observations from BGC Argo floats have suggested that the Southern Ocean may release more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere in the wintertime than previously thought. Data from the SOCCOM float array revealed strong seasonal outgassing at higher Antarctic latitudes, calling the strength of the Southern Ocean carbon sink into question.

Carranza and SOCCOM collaborators investigated whether float data viewed in aggregate from a storm’s perspective could reveal insights into carbon exchange in the Southern Ocean driven by storms.

Storms frequently pass through the Southern Ocean all year round. On average, any given location in this region will experience one storm every week with strong winds that last a few days. Storms affect the exchange of carbon dioxide at the ocean’s surface. The strong winds mix the surface waters, bringing deeper, cooler water from below up towards the surface.

Cooler waters can absorb more carbon, but deeper waters already contain more dissolved carbon from remineralization of organic matter than surface waters—how do these competing forces affect the air–sea carbon exchange?

A first-of-its-kind analysis of observations from SOCCOM’s float network has revealed that storms trigger a release of carbon dioxide in the Southern Ocean.

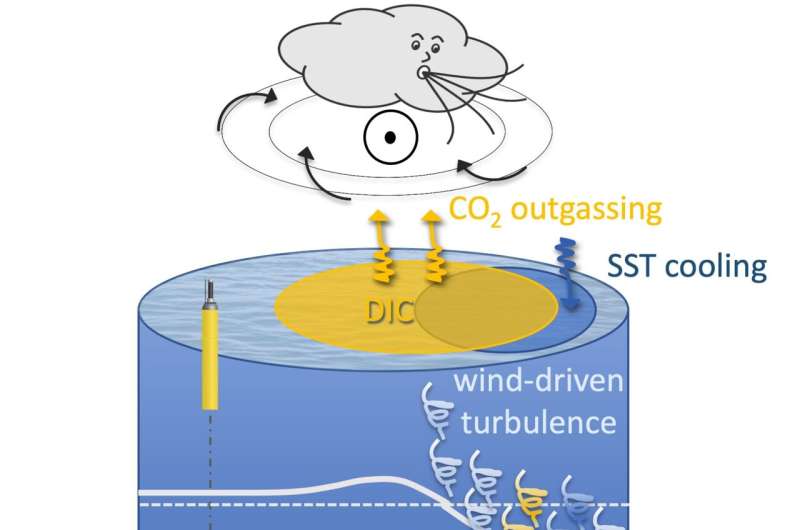

Using data collected by BGC Argo floats (yellow cylinders on the left), researchers have investigated how storms affect the exchange of carbon dioxide in the Southern Ocean. Westerly winds (•) that rotate clockwise around a low-pressure system generate upwelling at the core of the storm. The wind disturbance on the equatorward side enhances vertical mixing that deepens the mixed-layer depth (MLD). Upwelling and enhanced vertical mixing bring cold, carbon-rich waters (high inorganic dissolved carbon, or DIC) to the surface. Surface cooling induces absorption of carbon dioxide (ingassing, blue jagged arrow), but the increase in surface DIC induces the release of carbon dioxide (outgassing, yellow jagged arrows). The overall effect of a storm passing over the Southern Ocean is to induce carbon dioxide outgassing. © Magdalena Carranza/2024 MBARI

Atmospheric reanalyses combine past observations with models to give a detailed description of observed weather and climate, including storms. They are used to force ocean models, allowing researchers to study the history of carbon exchange between the ocean and the atmosphere.

The research team also used atmospheric reanalyses to identify and track storms. Pairing atmospheric storm data with data on ocean conditions collected by BGC Argo floats provided observational estimates of ocean-atmosphere carbon exchange recorded during a storm and in its aftermath.

Storm identification and tracking are more commonly used in atmospheric sciences to study how storms impact heat, moisture, rain patterns, and other meteorological conditions, but this sort of analysis has not yet been widely applied for oceanographic research. In fact, this study was the first to use such an analysis to examine ocean dynamics in the Southern Ocean during storms.

Ocean models with biogeochemistry can potentially predict how storms impact carbon pathways in the upper ocean and the air–sea carbon exchange. But aggregated observations of ocean conditions in the vicinity of a storm from SOCCOM’s float array allowed researchers to detect the release of natural carbon dioxide from the deep ocean into the atmosphere following a storm. Storm outgassing is not well reflected in current ocean models forced with atmospheric reanalysis.

During a storm, the Southern Ocean releases some of the carbon it has stored because carbon-rich water rises to the surface and is mixed up into the upper ocean through the effects of turbulence induced by strong winds. Outgassing is highest within a day of a storm’s passage. The amount of outgassing inferred from observations is larger than expected from forced ocean models.

“Storms mix the water column, causing both immediate and long-term effects on air–sea carbon exchange. We’ve learned the net impact is the release of carbon locked away in the ocean back into the atmosphere,” said Carranza.

“This work is helping fill in gaps in our understanding of carbon fluxes in the Southern Ocean. We were able to quantify the contribution of storms to the annual exchange. It turns out that storms play a big role in observations, accounting for approximately 25% of the annual flux, but their effect is greatly underestimated in forced ocean models.

“Since storms are so prevalent in the Southern Ocean, this could alter current estimates of the region’s contribution to the annual net carbon sink. The effects of storms need to be better represented in ocean models to reduce uncertainty in predictions of future climate.”

This work underscores the value of robotic technology as a vital tool for assessing and tracking ocean carbon. Models depend on data for validation—ocean models alone cannot fully represent the strong influence of storms on carbon exchange in the Southern Ocean.

Real-world observations from SOCCOM’s network of BGC Argo floats can help improve our understanding of air–sea carbon exchange to build better models that can more accurately predict how the ocean is changing.

Deploying advanced technology and sustaining the array of BGC Argo floats in the Southern Ocean and around the world is integral to understanding our changing ocean and future climate.

More information:

Magdalena M. Carranza et al, Extratropical storms induce carbon outgassing over the Southern Ocean, npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41612-024-00657-7

Provided by

Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

Citation:

First-of-its-kind analysis reveals importance of storms in air–sea carbon exchange in Southern Ocean (2024, August 14)