Climate disaster, pandemics, species extinction, violent conflict—we live in a time of multiple crises. Researchers and policymakers throughout the world are looking for ways to respond adequately to this many-headed monster—something easier said than done.

“Systemic risks increasingly converge in the Anthropocene, the age of human impacts,” says Dr. Alexandre Pereira Santos from the Human-Environment Relations research and teaching unit at LMU’s Department of Geography. “We know that these risks cause damages and losses, which may become even greater when hazards interact and multiply their impacts.”

This was the case, for example, when the COVID-19 crisis not only impacted people’s health, but also drove many into poverty. Yet for many crises, the complexity of the interactions is only partially understood. Science has trouble integrating the various scales of analysis, disciplinary perspectives, and sectors of society.

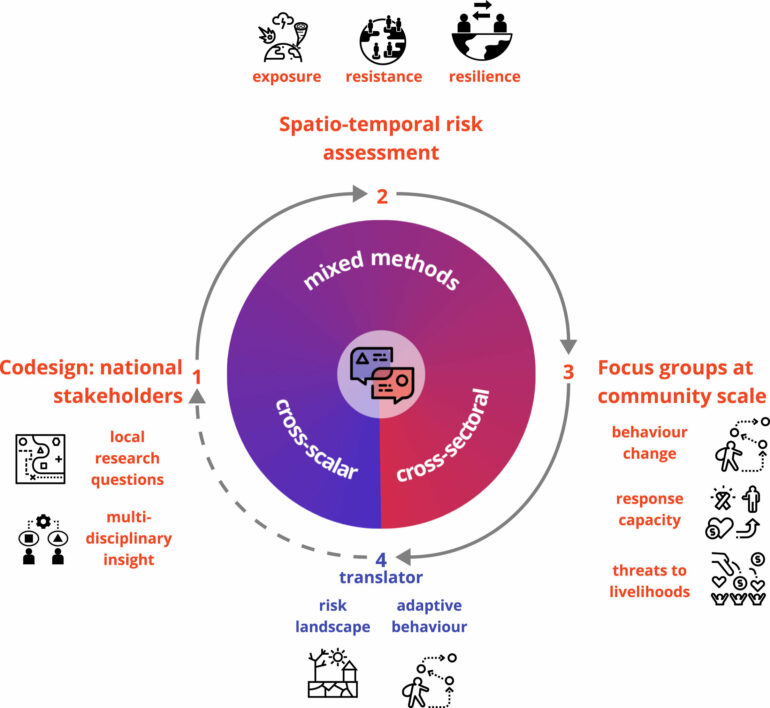

In a paper published recently in the journal One Earth, Pereira Santos and his colleagues from Universität Hamburg and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology present a novel approach for dealing with this complexity. Their goal was to take the various aspects into account and bring them together.

“Our novel concept uses well-known analytical methods from climate and social sciences and connects them by means of a translator,” says Pereira Santos. This translator brings together the different perspectives, spatial and temporal scales, and social sectors and allows for a more nuanced description of health and climate crises. Moreover, it does so in a way that preserves the complexity and diversity of evidence to support more inclusive and context-aware adaptation policies.

“Before our approach, researchers often had to choose which aspects to consider in order to avoid information overload. Or they had to perform general analyses of multiple risks, regions, or social sectors, resulting in the loss of information,” explains the geographer. These losses include things like interactions between risks, individual social circumstances, the effects on the economy, or the risk exposure of various groups of people.

The authors point out that risk research is often limited by disciplinary approaches and single-sector or scale analyses, skewing policy advice towards biased, misguided, and unfair outcomes. They propose going beyond such trade-offs in favor of addressing the complexity of the various risks in an organized manner without losing breadth and depth of analysis.

“Our translator model brings together various sources of evidence and joins them into a meaningful whole,” summarizes Pereira Santos. “The framework we propose provides a deep and broad (that is to say, integrated and diverse) description of risk factors, to support research and policymaking with systematic and context-sensitive evidence.”

More information:

Alexandre Pereira Santos et al, Integrating broad and deep multiple-stressor research: A framework for translating across scales and disciplines, One Earth (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.oneear.2024.09.006

Provided by

Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich

Citation:

Geographers present new risk model that offers more nuanced view of complex crises (2024, October 23)