Common methods of communicating flood risk may create a false sense of security, leading to increased development in areas threatened by flooding.

This phenomenon, called the “safe development paradox,” is described in a new paper from North Carolina State University. Lead author Georgina Sanchez, a research scholar in NC State’s Center for Geospatial Analytics, said this may be an unintended byproduct of how the Federal Emergency Management Agency classifies areas based on their probability of dangerous flooding.

The findings are published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Known as flood mapping, this classification system describes areas in terms of their likelihood of being flooded each year. These classifications are then used to determine all kinds of regulatory requirements, such as whether a developer or homeowner must purchase flood insurance. For example, an area with a 1% chance of flooding in any given year would be referred to as a 100-year floodplain—and anything in the 100-year floodplain is designated “high risk.”

However, by designating the 100-year floodplain as “high risk,” regulators may unintentionally give the mistaken assumption that anything outside that zone carries no risk, Sanchez said.

“What our current methods do is draw a line between the 100-year floodplain, which is considered ‘high risk,’ and everything outside of it. We communicate flood risk in a way that says you are either on the ‘at risk’ side of that line, or the ‘minimal risk’ side,” Sanchez said.

“If you are on the ‘safe’ side, then you are not required to purchase flood insurance or meet strict structural requirements. It then becomes more affordable to live just outside the floodplain, where the perceived risk is lower, yet you are still close to the beautiful lakes, rivers and coastlines we love.”

This, Sanchez said, creates a mechanism that clusters development just beyond the highest-risk flood areas, even though in reality the risk extends beyond the floodplain’s edge.

Previous research on the safe development paradox has focused on the “levee effect,” in which the creation of flood-prevention structures gives the false impression that an area is safe from flooding and thus attracts increased development. This in turn leads to concentrated losses if a flood event exceeds what the flood-prevention structure was designed to withstand.

In focusing on regulatory floodplain mapping instead of these structures, Sanchez and her collaborators uncovered another example of the paradox, where efforts to reduce flood risk paradoxically intensify it by promoting development immediately outside of designated “high-risk” zones.

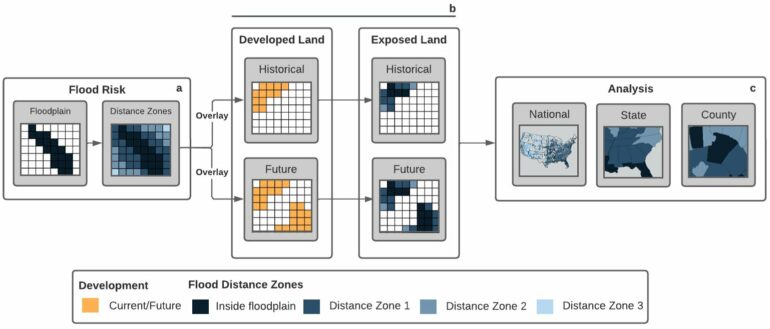

By overlaying floodplain maps from over 2,300 counties with data on prior development trends and simulated future development, researchers found evidence for the safe development paradox from the national level down to the county level. The study found that as much as 24% of all development nationwide occurs within 250 meters of a 100-year floodplain, and projections indicate that this number will continue to grow through at least the year 2060 without new policies to prevent flood exposure.

While the study concluded in 2019, these findings are apparent in the recent destruction caused by Hurricane Helene in western North Carolina, Sanchez said.

“Because of the steep topography in places like western North Carolina, there is an even greater concentration of development compared to flatter areas,” she said. “Developers tend to seek land that is flat enough to build on, which often happens to be along stream networks and closer to flood-prone areas.

“When I saw the news after Helene and looked at the images from the region, I could painfully see the findings of our study reflected in those scenes.”

More information:

Georgina M. Sanchez et al, The safe development paradox of the United States regulatory floodplain, PLOS ONE (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0311718

Provided by

North Carolina State University

Citation:

How we classify flood risk may give developers and home buyers a false sense of security (2025, January 6)