Earth’s tropical rain belt, responsible for monsoons that sustain billions of people and vibrant ecosystems, has long been a reliable feature of the planet’s climate. But new research reveals this vital system wasn’t always so dependable.

A study published in Geophysical Research Letters shows that during the early Eocene—the hottest period in the last 65 million years—the rain belt’s seasonal shifts weakened dramatically. These ancient changes could offer critical warnings about the impact of modern global warming.

A greenhouse climate 50 million years ago

The early Eocene was a time of intense volcanic activity, releasing massive amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide levels surged to over 1,600 ppmv—approximately six times preindustrial levels—causing global temperatures to rise by 9–23°C.

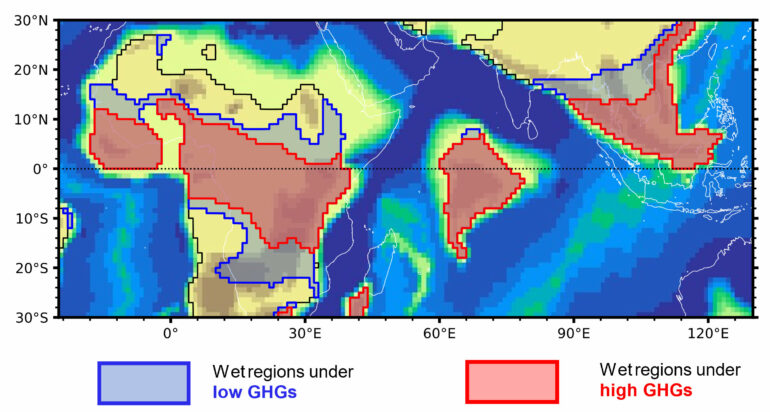

Researchers from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences used climate simulations and reconstructions of ancient climate conditions to uncover a striking pattern: extreme warming expanded subtropical dry zones and shrank tropical wet regions.

Central to this disruption was a reduced seasonal movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)—a band of clouds and heavy rainfall that shifts north and south along with the seasons.

The mechanism underlying the muted swing

The ITCZ’s seasonal movement is controlled by the tug-of-war between solar radiation and latent heat flux—the energy transported into the atmosphere as water evaporates from ocean surfaces. In modern climates, cooler oceans moderate evaporation’s sensitivity to wind, allowing the ITCZ to shift largely into the summer hemisphere as the sun’s position changes.

“In the early Eocene, much warmer oceans made evaporation far more sensitive to wind speed,” said Dr. Ren Zikun, the study’s lead author. “This heightened sensitivity amplified wind-driven differences in surface evaporation between hemispheres, disrupting the balance with solar heating. The result was a reduced seasonal reach of the ITCZ and a contraction of tropical wet zones.”

Relevance to today’s warming world

If current greenhouse gas emissions continue unchecked, carbon dioxide levels could rise to levels seen during the early Eocene. Prof. Zhou Tianjun, the corresponding author, highlighted the study’s broader implications, saying, “The deep-time history of Earth provides critical evidence of how greenhouse gases reshape the global climate.

“While the Eocene’s changes occurred over millennia, similar shifts could happen at an unprecedented pace due to human activities. This serves as a stark warning about the urgent need for mitigation efforts.”

More information:

Zikun Ren et al, Enhanced “Wind‐Evaporation Effect” Drove the “Deep‐Tropical Contraction” in the Early Eocene, Geophysical Research Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1029/2024GL108836

Provided by

Chinese Academy of Sciences

Citation:

Lessons from Earth’s hottest epoch in the last 65 million years: How global warming could shrink the tropics’ rain belt (2024, December 5)