Research from scientists at Louisiana State University and Indiana University reveals new information about the role humans have played in large-scale land loss in the Mississippi River Delta—crucial information in determining solutions to the crisis.

The study published today in Nature Sustainability compares the impacts of different human actions on land loss and explains historical trends. Until now, scientists have been unsure about which human-related factors are the most consequential, and why the most rapid land loss in the Mississippi River Delta occurred between the 1960s and 1990s and since has slowed down.

“What we found was really surprising,” said Doug Edmonds, lead author on the study and an associate professor of Earth and atmospheric sciences at Indiana University Bloomington. “It is tempting to link the land loss crisis to dam building in the Mississippi River Basin—after all, dams have reduced the sediment in the Mississippi River substantially. But in the end, building levees and extracting subsurface resources have created more land loss.”

The current Mississippi River Delta formed over the past 7,000 years through sediment deposition from the river near the Gulf Coast. But due to human efforts to harness the river and protect communities, sediment accumulation is no longer sufficient to sustain the delta. As a result, coastal Louisiana has lost about 1,900 square miles of land since the 1930s, according to the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority.

The study found that only about 20% of the land loss is due to dam building, while levee building and extracting subsurface resources, such as oil and gas, each account for about 40% of the Mississippi River Delta land loss. The study also suggests the most rapid land loss and the recent deceleration might be related to the reduction of subsurface resource extraction.

To conduct their study, researchers re-created the land loss for an area in the Mississippi River Delta called the Barataria Basin. They used a model that describes the sediment budget, which is the balance between sediment flowing in and out of a coastal system. Using that model, they quantified the impact that building dams and levees and extracting subsurface resources had on land loss.

LSU leaders on the study were Robert R. Twilley, professor of oceanography and coastal sciences and interim vice president of research and economic development; Samuel J. Bentley, professor and the Billy and Ann Harrison Chair in Sedimentary Geology; and Kehui Xu, director of the LSU Coastal Studies Institute and James P. Morgan Distinguished Professor of Oceanography & Coastal Sciences along with LSU Civil & Environmental Engineering alumnus Christopher G. Siverd, who is a coastal engineer at Moffatt & Nichol.

“This study emphasizes the importance of doing a broad systems analysis of complex problems, so we really can have confidence in the solutions we’re proposing to reverse land loss and protect our land and people,” Twilley said. “There’s a possibility river diversions might have more impact in building wetlands than we anticipated.”

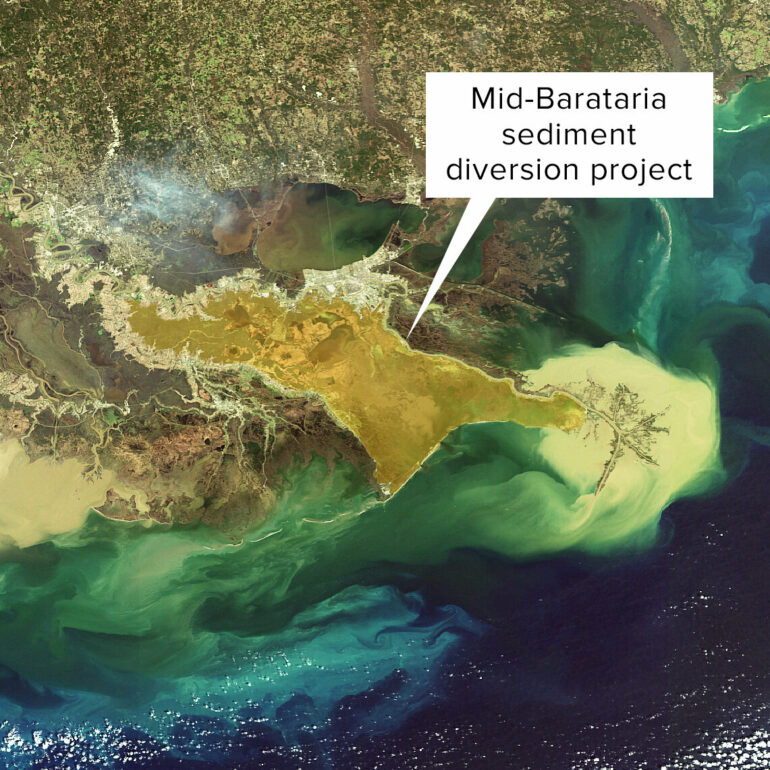

The 2023 Coastal Master Plan for Louisiana prioritizes restoring the processes that naturally build land in the delta. The Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, which is the largest coastal land restoration project in Louisiana at more than $2 billion, will release sediment and water from the Mississippi River into the adjacent Barataria Basin.

“Our work suggests the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion is the right tool for the job to counter land loss due to subsidence and sea level rise,” Bentley said. “Overall, this study offers perhaps a rosier outlook than some other analyses on our ability to engineer with nature to reverse land loss.”

As resource extraction has decreased in recent years, the relative impact of levees on Louisiana coastal land loss is trending higher. That impact, however, could potentially be offset by sediment diversions.

“Findings strongly suggest the Mid-Barataria sediment diversion and other sediment diversions along the Mississippi River will provide long-term land-building capability and reduce future land loss in southeast Louisiana,” Siverd said.

More information:

Douglas Edmonds, Land loss due to human-altered sediment budget in the Mississippi River Delta, Nature Sustainability (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41893-023-01081-0. www.nature.com/articles/s41893-023-01081-0

Provided by

Louisiana State University

Citation:

New study compares human contributions to Mississippi River Delta land loss, hints at solutions (2023, March 6)