A new analysis of rocks thought to be at least 2.5 billion years old by researchers at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History helps clarify the chemical history of Earth’s mantle—the geologic layer beneath the planet’s crust.

The findings hone scientists’ understanding of Earth’s earliest geologic processes, and they provide new evidence in a decades-long scientific debate about the geologic history of Earth. Specifically, the results provide evidence that the oxidation state of the vast majority of Earth’s mantle has remained stable through geologic time and has not undergone major transitions, contrary to what has been suggested previously by other researchers.

“This study tells us more about how this special place in which we live came to be the way it is, with its unique surface and interior that have allowed life and liquid water to exist,” said Elizabeth Cottrell, chair of the museum’s department of mineral sciences, curator of the National Rock Collection and co-author of the study.

“It’s part of our story as humans because our origins all trace back to how Earth formed and how it has evolved.”

The study, published in the journal Nature, centered on a group of rocks collected from the seafloor that possessed unusual geochemical properties. Namely, the rocks show evidence of having melted to an extreme degree with very low levels of oxidation; oxidation is when an atom or molecule loses one or more electrons in a chemical reaction.

With the help of additional analyses and modeling, the researchers used the unique properties of these rocks to show that they likely date back to at least 2.5 billion years ago during the Archean Eon. Further, the findings show that the Earth’s mantle has overall retained a stable oxidation state since these rocks formed, in contrast to what other geologists have previously theorized.

“The ancient rocks we studied are 10,000 times less oxidized than typical modern mantle rocks, and we present evidence that this is because they melted deep in the Earth during the Archean, when the mantle was much hotter than it is today,” Cottrell said.

“Other researchers have tried to explain the higher oxidation levels seen in rocks from today’s mantle by suggesting that an oxidation event or change has taken place between the Archean and today. Our evidence suggests that the difference in oxidation levels can simply be explained by the fact that Earth’s mantle has cooled over billions of years and is no longer hot enough to produce rocks with such low oxidation levels.”

The research team—including lead study author Suzanne Birner who completed a pre-doctoral fellowship at the National Museum of Natural History and is now an assistant professor at Berea College in Kentucky—began their investigation to understand the relationship between Earth’s solid mantle and modern seafloor volcanic rocks.

The researchers started by studying a group of rocks that were dredged from the seafloor at two oceanic ridges where tectonic plates are spreading apart and the mantle is churning up to the surface and producing new crust.

The two places the studied rocks were collected from, the Gakkel Ridge near the North Pole and the Southwest Indian Ridge between Africa and Antarctica, are two of the slowest-spreading tectonic plate boundaries in the world. The slow pace of the spreading at these ocean ridges means that they are relatively quiet, volcanically speaking, compared to faster spreading ridges that are peppered with volcanoes such as the East Pacific Rise. This means that rocks collected from these slow-spreading ridges are more likely to be samples of the mantle itself.

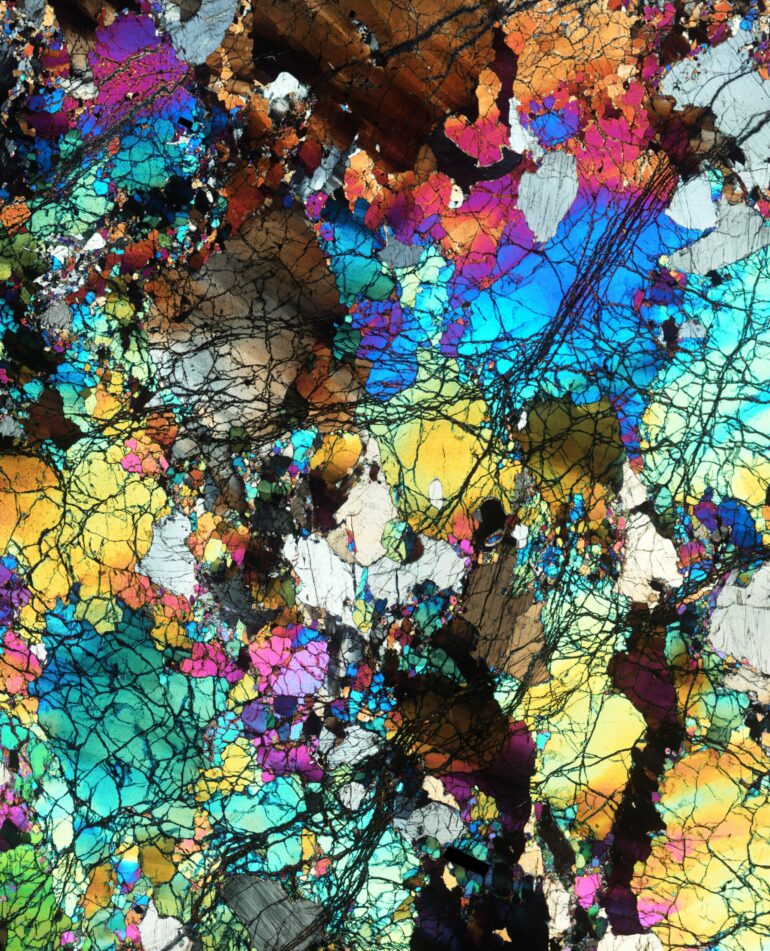

An ancient rock dredged from the seafloor and studied by the research team. © Tom Kleindinst

When the team analyzed the mantle rocks they collected from these two ridges, they discovered they had strange chemical properties in common. First, the rocks had been melted to a much greater extent than is typical of Earth’s mantle today. Second, the rocks were much less oxidized than most other samples of Earth’s mantle.

To achieve such a high degree of melting, the researchers reasoned that the rocks must have melted deep in the Earth at very high temperatures. The only period of Earth’s geologic history known to include such high temperatures was between 2.5 and 4 billion years ago during the Archean Eon.

Consequently, the researchers inferred that these mantle rocks may have melted during the Archean, when the inside of the planet was 360–540 degrees Fahrenheit (200–300 degrees Celsius) hotter than it is today.

Being so extremely melted would have protected these rocks from further melting that could have altered their chemical signature, allowing them to circulate in Earth’s mantle for billions of years without significantly changing their chemistry.

“This fact alone doesn’t prove anything,” Cottrell said. “But it opens the door to these samples being genuine geologic time capsules from the Archean.”

To explore the geochemical scenarios that might explain the low oxidation levels of the rocks collected at Gakkel Ridge and the Southwest Indian Ridge, the team applied multiple models to their measurements. The models revealed that the low oxidation levels they measured in their samples could have been caused by melting under extremely hot conditions deep in the Earth.

Both lines of evidence backed the interpretation that the rocks’ atypical properties represented a chemical signature from having melted deep in the Earth during the Archean, when the mantle could produce extremely high temperatures.

The stern of the research vessel, the R/V Knorr while at sea in 2004. The A-frame structure holds the giant metal and chain bucket which is lowered more than 10,000 feet below the ocean surface and dragged along the seafloor to collect geologic samples. © Emily Van Ark

Previously, some geologists have interpreted mantle rocks with low oxidation levels as evidence that the Archean Earth’s mantle was less oxidized and that, through some mechanism, it has become more oxidized over time.

Proposed oxidation mechanisms include a gradual increase in oxidation levels due to a loss of gases to space, recycling of old seafloor by subduction and ongoing participation of Earth’s core in mantle geochemistry. But, to date, proponents of this view have not coalesced around any one explanation.

Instead, the new findings support the view that the oxidation level of Earth’s mantle has been largely steady for billions of years, and that the low oxidation seen in some samples of the mantle were created under geologic conditions the Earth can no longer produce because its mantle has since cooled.

So, instead of some mechanism making Earth’s mantle more oxidized over billions of years, the new study argues that the high temperatures of the Archean made parts of the mantle less oxidized. Because Earth’s mantle has cooled since the Archean, it cannot produce rocks with super low oxidation levels anymore. Cottrell said the process of the planet’s mantle cooling provides a much simpler explanation: Earth simply does not make rocks like it used to.

Cottrell and her collaborators are now seeking to better understand the geochemical processes that shaped the Archean mantle rocks from the Gakkel Ridge and the Southwest Indian Ridge by simulating in the lab the extremely high pressures and temperatures found in the Archean.

This research contributes to the museum’s Our Unique Planet initiative. As a public–private research partnership, Our Unique Planet investigates what sets Earth apart from its cosmic neighbors by exploring the origins of the planet’s oceans and continents, as well as how minerals may have served as templates for life.

In addition to Birner and Cottrell, Fred Davis of the University of Minnesota Duluth and Jessica Warren of the University of Delaware were co-authors of the study.

More information:

Suzanne Birner, Deep, ancient melting recorded by ultra-low oxygen fugacity in peridotites, Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07603-w. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07603-w

Citation:

New study supports stable mantle chemistry dating back to Earth’s early geologic history (2024, July 24)