Each winter, spring, and summer, extreme weather forecasters and researchers meet to test the latest, most promising severe weather forecast tools and innovations to see how they perform in real-world settings.

These testbed experiments, orchestrated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), forecast winter storms, severe thunderstorms, and flash flooding respectively.

The Hydrometeorology Testbed recently held the 12th annual Winter Weather Experiment (WWE). An immersive, collaborative, “research-to-operations” experience, it brought together members of the forecasting, research, and academic communities to evaluate and discuss winter weather forecast challenges.

“We generate operational forecasts using new inputs or new models testing how well they work,” said Keith Brewster, senior research scientist and operations director of the Center for Analysis and Prediction of Storms (CAPS) at the University of Oklahoma. “If we promise a forecast where thunderstorms occur, can we expect a forecaster to use it?”

Humming along in the background of the experiment are supercomputers at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC)—among the fastest available to academic researchers in the world.

The CAPS team began using TACC systems for the Hazardous Weather Testbed Spring Experiment in 2011 to better predict severe thunderstorms. They computed at that time on the original Stampede supercomputer at TACC—the 6th fastest in the world in its prime. From 2017-2021, they used Stampede2 (12th fastest) through the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE). Since 2021, they have used Frontera, the fastest university supercomputer in the world and currently the 13th fastest overall.

“What TACC and XSEDE offer us is the ability to do these real-time or near-real-time experiments,” Brewster said.

The CAPS team submits their forecasting simulations by 10:00pm, after weather observations and other input data comes in for the 00 UTC cycle. The simulations run overnight and are ready by 8:00am the next morning, predicting weather events out to three-and-a-half days.

“On Stampede, we worked with TACC to have a special queue set up where we have a dedicated number of cores allocated to us,” Brewster said. This type of “urgent computing” has become a hallmark of TACC, enabling the center to forecast hurricane storm surge, monitor space junk in low Earth orbit, and power COVID-19 models. “More recently, on Frontera, the capacity is such that we can run in the regular queue, using a VIP priority, making our use more efficient and less disruptive to other research users.”

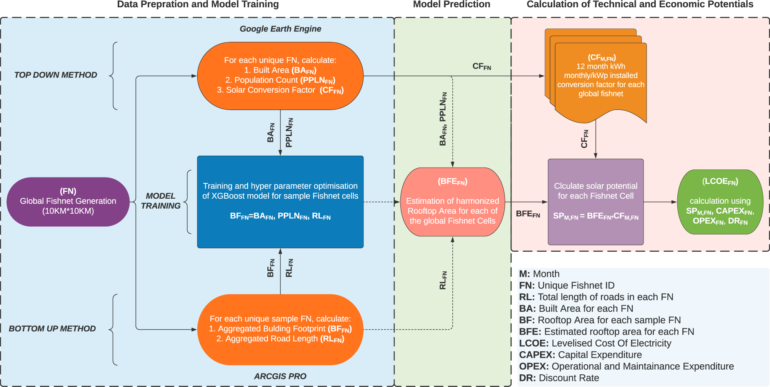

This year’s Winter Weather Experiment had three key science goals: to subjectively gauge the utility of convection-allowing model (CAM) forecasts to improve two-to-three day snowfall forecasts; objectively score the snowfall forecasts using community standard verification systems; and determine the optimal combination of physics to use in next-generation models.

The team was primarily interested in predicting the amount of snowfall accumulation, but they also tested their ability to determine the differences between snow, sleet, and freezing rain in forecasts, and predict other facets of winter weather, like wind speed.

“Giving forecasters the opportunity to use these experimental models in real situations allows forecasters and researchers to determine the strengths, operational challenges, and forecaster usability early on in the development stage,” said James Correia Jr., coordinator for the Hydrometeorology Testbed. “This allows us, together, in NOAA testbeds, to make improvements in our forecasting process, models, and the way we approach and solve research and operational challenges.”

Recent testbed programs have also included the important task of evaluating NOAA’s next-generation weather model, the FV3 model. This model has shown success in global-scale forecasting, and the agency plans to also utilize it operationally for much higher resolution regional modeling as represented in the high-impact testbeds. The new multi-scale forecast system is known as the Unified Forecasting System (UFS).

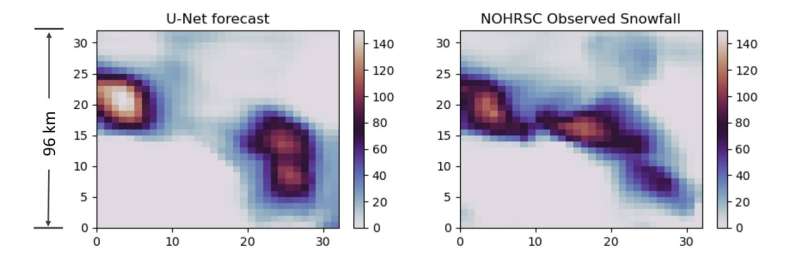

The team’s machine learning model is already predicting the scale and orientation of mesoscale/sub-mesoscale snow precipitation features with reasonable accuracy, says Brewster. © Brewster, Snook, et al.

“In addition to real-time testing, CAPS has been using TACC supercomputers to rerun cases to identify the root cause of issues that were identified during prior testbeds,” Brewster said. “This leads to tuning and other enhancements to the original codes.”

The Winter Weather Experiment ran for 27 case days on Frontera in near-real-time over the course of the winter, including objective verification and machine learning training—a forward-looking aspect of the research. Brewster presented the results as a webinar organized by NOAA in March 2022.

Following the experiment, researchers typically do more detailed studies on specific facets of the forecasts, with funding from NOAA’s Weather Program Office as part of the Testbed competition in collaboration with NOAA’s Weather Prediction Center and Storm Prediction Center—both divisions of the National Weather Service.

Testing ensemble consensus methods

Most weather watchers are familiar with the idea of ensemble models—the swarms of tracks that represent the results from various simulations, which are averaged and interpreted by weather forecasters.

Using Frontera, Brewster’s team generates real-time ensemble forecasts.

“In decision theory, it has been shown that when you get a consensus of experts, you get better advice than from a single person,” Brewster said. “Thanks to TACC, we can generate 13 models—13 ‘experts’ predicting what the weather is going to be. From there, we’re working on how to develop ensemble consensus products that best help improve forecasts.”

Sometimes usability by a human operator trumps pure prediction skills. Communicating the consensus decision from an ensemble of forecasts is such an example.

“We researchers are in there, observing and participating, for one week—as if we were in the weather office, creating forecasts, so people like myself can see the issues,” Brewster explained. “We try to be realistic: Can someone really look at ten to 15 models? Or does it create more uncertainty?”

One approach the CAPS team has been exploring for ensemble consensus methods is the local probability match mean (LPM) method. The LPM method divides an area into patches, calculates the atmospheric dynamics over that patch, and distributes the results locally. (Nathan Snook and the CAPS team described the method, and compared various ways of computing this mean, in a 2020 paper in Geophysical Research Letters.)

An assessment of the accuracy by NOAA showed the local probability match mean (LPM) performed slightly worse than probability match (PM) mean in objective precipitation scoring.

“But this is where the testbed activities come in,” Brewster said. “When a human looks at a forecast, they’re not looking at raw numbers at a site. They’re looking at the shape—consensus reflectivity—and in this respect, LPM was deemed to be better. That was a win for our team.”

The LPM has since been implemented in NOAA’s operational High Resolution Ensemble Forecast system. This is the goal of the NOAA Testbed program: taking research ideas and getting them through testing and evaluation in quasi-operational settings to actual operational deployment.

“That’s what we call technology transfer,” Brewster said. “There’s a tech divide where researchers like our team work on models, produce papers, and it can be hard to get new models or concepts into the operations. Tech transfer happened because it was proven, not just running on TACC and to other researchers, but to other forecasters. That gets us over the divide from journal articles to impacting real-world forecasts.”

More information:

Nathan Snook et al, Comparison and Verification of Point‐Wise and Patch‐Wise Localized Probability‐Matched Mean Algorithms for Ensemble Consensus Precipitation Forecasts, Geophysical Research Letters (2020). DOI: 10.1029/2020GL087839

Provided by

University of Texas at Austin

Citation:

Next-generation weather models cross the divide to real-world impact (2022, May 18)