The COVID pandemic shutdowns in South Asia greatly reduced the concentration of short-lived cooling particles in the air, while the concentration of long-lived greenhouse gases was barely affected. Researchers were thus able to see how reduced emissions of air pollution leads to cleaner air but also stronger climate warming.

It is well known that emissions of sulfur and nitrogen oxides and other air pollutants lead to the formation of aerosols (particles) in the air that can offset, or mask, the full climate warming caused by greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane. But there has been a lack of knowledge about this “masking effect.” In order to determine the size, large-scale experiments involving huge regions would be required—this is infeasible.

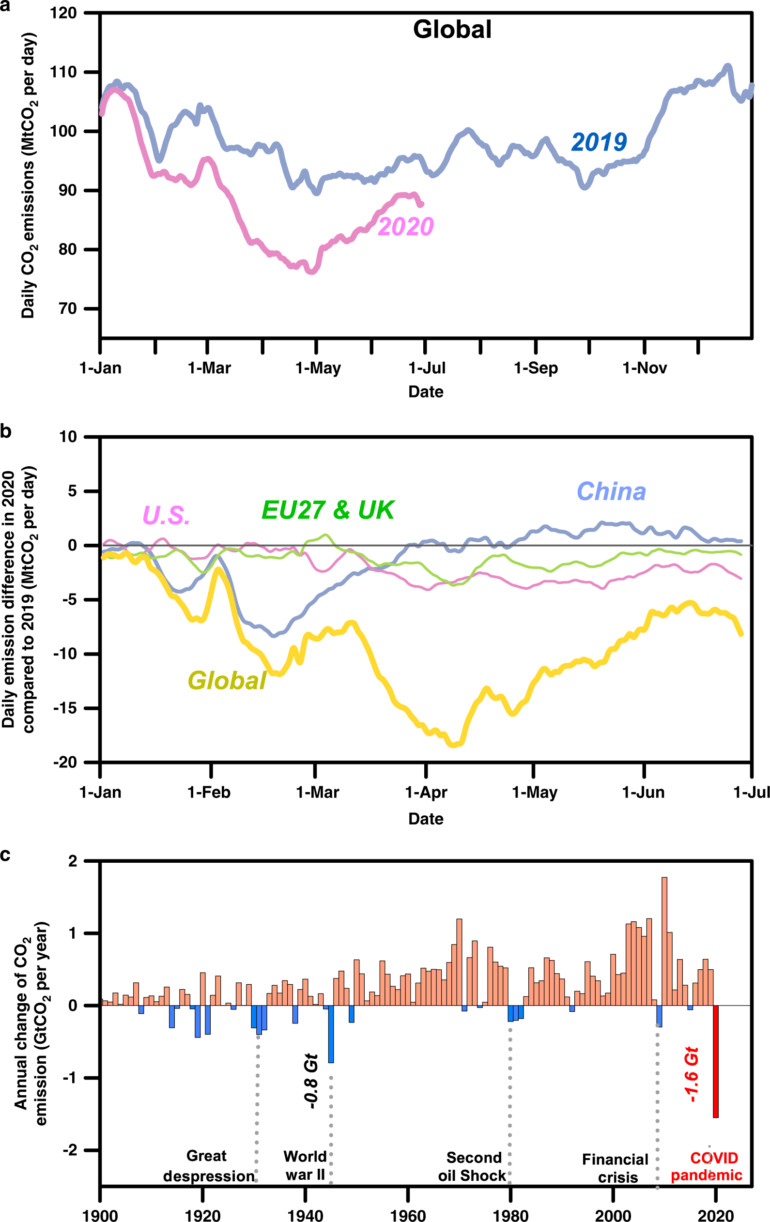

The COVID pandemic became such a “natural” experiment. In the spring of 2020, the activity of many industries and transportation worldwide decreased due to pandemic restrictions. This created a unique opportunity to study what happens to the climate if emissions of gases and aerosols are rapidly reduced.

At Hanimaadhoo, a measuring station in the northernmost Maldives off the coast of India, researchers have been measuring the atmospheric composition and radiation for soon two decades. The measuring station is strategically placed to capture air masses from the Asian subcontinent and located in an area with few regional emission sources. When emissions suddenly decreased during the pandemic in South Asia (mainly Pakistan, India and Bangladesh), an opportunity was created to see what impact this had on the climate.

Short-lived air particles decreased but not greenhouse gases

A new article in the journal npj Climate and Atmospheric Science shows that the concentrations of polluting short-lived air particles decreased significantly, while the concentrations of longer-lived greenhouse gases were barely affected in the air mass over South Asia. The cooling effect of the aerosols comes from the fact that they reflect incoming solar radiation back into space. With a lower aerosol content, there is less cooling, and thus less “masking” of the warming effect of the significantly longer-lived climate gases. Measurements taken at the same time over the northern Indian Ocean revealed a seven percent increase in solar radiation reaching the Earth’s surface, thus increasing temperatures.

Örjan Gustafsson in the tower at Hanimaadhoo measuring station. © Joakim Romson

“Through this large-scale geophysical experiment, we were able to demonstrate that while the sky became bluer and the air cleaner, climate warming increased when these cooling air particles were removed,” says Professor Örjan Gustafsson at Stockholm University, who is responsible for the measurements in the Maldives and who led the study.

The results show that a complete phasing out of fossil fuel combustion in favor of renewable energy sources with zero emissions could result in rapid “unmasking” of aerosols, while greenhouse gases linger.

“During a couple of decades, emission reductions risk leading to net climate warming due to the ‘masking’ effect of air particles, before the temperature reduction from reduced greenhouse gas emissions takes over. But despite an initial climate warming effect, we obviously still urgently need a powerful emission reduction,” says Örjan Gustafsson.

More information:

H. R. C. R. Nair et al, Aerosol demasking enhances climate warming over South Asia, npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41612-023-00367-6

Provided by

Stockholm University

Citation:

Reduced emissions during the pandemic led to increased climate warming, reveals study (2023, May 31)