More frequent and longer-lasting droughts caused by rising global temperatures pose significant risks to people and ecosystems around the world, according to new research from the University of East Anglia (UEA).

The study shows that even a modest temperature increase of 1.5°C will spell serious consequences in India, China, Ethiopia, Ghana, Brazil and Egypt. These six countries were selected for study in the UEA project because they provide a range of contrasting sizes and different levels of development on three continents spanning tropical and temperate biomes, and contain forest, grassland and desert habitats.

The findings, “Quantification of meteorological drought risks between 1.5 °C and 4 °C of global warming in six countries,” are published today in the journal Climatic Change.

The paper, led by Dr. Jeff Price and his colleagues in the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at UEA, quantified the projected impacts of alternative levels of global warming upon the probability and length of severe drought in the six countries.

Dr. Price, Associate Professor of Biodiversity and Climate Change, said, “Current pledges for climate change mitigation, which are projected to still result in global warming levels of 3 °C or more, would impact all the countries in this study.

“For example, with 3 °C warming, more than 50% of the agricultural area in each country is projected to be exposed to severe droughts lasting longer than one year in a 30-year period. Using standard population projections, it is estimated that 80% to 100% of the population in Brazil, China, Egypt, Ethiopia and Ghana (and nearly 50% of the population of India) are projected to be exposed to a severe drought lasting one year or longer in a 30-year period.

“In contrast, we find that meeting the long-term temperature goal of the Paris Agreement, that is limiting warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, is projected to greatly benefit all of the countries in this study, greatly reducing exposure to severe drought for large percentages of the population and in all major land cover classes, with Egypt potentially benefiting the most.”

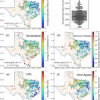

In the 1.5 °C warming scenario, the drought probability is projected to triple in Brazil and China, nearly double in Ethiopia and Ghana, increase slightly in India, and substantially increase in Egypt.

In a 2 °C warming scenario, the probability of drought is projected to quadruple in Brazil and China; double in Ethiopia and Ghana; reach greater than 90% probability in Egypt; and nearly double in India.

In a 3 °C warming scenario, the probability of drought projected to be in Brazil and China is 30-40%; 20-23% in Ethiopia and Ghana; 14% in India, but nearly 100% in Egypt.

Finally in a 4 °C warming scenario, the probability of drought projected in Brazil and China is nearly 50%; 27-30% in Ethiopia and Ghana; nearly 20% in India; and 100% in Egypt.

In most countries, the projected increase in drought probability increases approximately linearly with increasing temperature. The exception is Egypt, where even slight amounts of global warming potentially lead to large increases in drought probability.

Prof Rachel Warren, leader of the overall study of which this paper is one output, said, “Not only does the area exposed to drought increase with global warming, but it also increases the length of the droughts. In Brazil, China, Ethiopia, and Ghana, droughts of longer than two years are projected to occur even in a 1.5 °C warming scenario.”

In a 2 °C warming scenario, the length of droughts projected in all countries (except India) are projected to exceed three years. In a 3 °C warming scenario, droughts are projected to approach 4–5 years in length and in a 4 °C warming scenario, severe droughts of longer than five years are projected for Brazil and China, with severe drought the new baseline condition.

Also, the percentage of land projected to be exposed to a severe drought of longer than 12 months in a 30-year period is expected to increase rapidly by the 1.5 °C warming scenario in Brazil, China and Egypt, and in areas of permanent snow and ice in India.

India and China both have large areas currently under “permanent” ice and snow cover. However, in the 3 °C warming scenario, 90% of these areas are projected to face severe droughts lasting longer than a year in a 30-year period.

These areas form the headwaters of many major river systems, and thus the water supply for millions of people downstream. Increasing probability and duration of severe drought points to potential declines in water storage in the Chinese Himalayas in the form of snow and ice.

Drought can have major impacts on biodiversity, agricultural yields and economies. This study indicates that all six of the countries will need to deal with water stress in the agricultural sector, potentially through shifting crop varieties or through irrigation, if water is available. The amount of adaptation required to cope with this increase in drought therefore increases rapidly with global warming.

Urban areas fare only slightly better and generally show the same pattern as above. Areas along rivers and streams or with reservoirs may fare better, depending on competition for water resources and headwater sources.

Prof Warren said, “Meeting the Paris Accords could have major benefits in terms of reducing severe drought risk in these six countries, in all major land cover classes and for large percentages of the population worldwide. This requires urgent global scale action now to stop deforestation (including in the Amazon) in this decade, and to decarbonize the energy system in this decade, so that we can reach global net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.”

More information:

Quantification of meteorological drought risks between 1.5 °C and 4 °C of global warming in six countries, Climatic Change (2022). DOI: 10.1007/s10584-022-03359-2

Provided by

University of East Anglia

Citation:

Rising global temperatures point to future widespread droughts (2022, September 27)