In the history of Major League Baseball, first came the low-scoring dead-ball era, followed by the modern live-ball era characterized by power hitters such as Babe Ruth and Henry “Hank” Aaron. Then, regrettably, was the steroid era of the 1990s and early 2000s.

Now, could baseball be on the cusp of a “climate-ball” era where higher temperatures due to global warming increasingly determine the outcome of a game?

A new Dartmouth College study suggests it may be. A report in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society found that more than 500 home runs since 2010 can be attributed to higher-than-average temperatures resulting from climate change—with several hundred more home runs per season to come with future warming.

While the researchers attribute only 1% of recent home runs to climate change, they found that rising temperatures could account for 10% or more of home runs by 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions and climate change continue unabated.

“There’s a very clear physical mechanism at play in which warmer temperatures reduce the density of air. Baseball is a game of ballistics, and a batted ball is going to fly farther on a warm day,” said senior author Justin Mankin, an assistant professor of geography.

The researchers analyzed more than 100,000 major league games and 220,000 individual hits to correlate the number of home runs with the occurrence of unseasonably warm temperatures. They then estimated the extent to which the reduced air density that results from higher temperatures was the driving force in the number of home runs on a given day compared to other games.

Lead author Christopher Callahan, a doctoral candidate in geography at Dartmouth who conceived of the study, said the researchers accounted for factors such as the use of performance-enhancing drugs, the construction of bats and balls, and the adoption of cameras, launch analytics, and other technology intended to optimize a batter’s power and distance.

“We asked whether there are more home runs on unseasonably warm days than on unseasonably cold days during the course of a season,” Callahan said. “We’re able to compare those days with the implicit assumption that the other factors affecting batter performance don’t vary day to day or are affected if a day is unseasonably warm or cold.”

“We don’t think temperature is the dominant factor in the increase in home runs—batters are now primed to hit balls at optimal speeds and angles,” Callahan said. “That said, temperature matters and we’ve identified its effect. While climate change has been a minor influence so far, this influence will substantially increase by the end of the century if we continue to emit greenhouse gases and temperatures rise.”

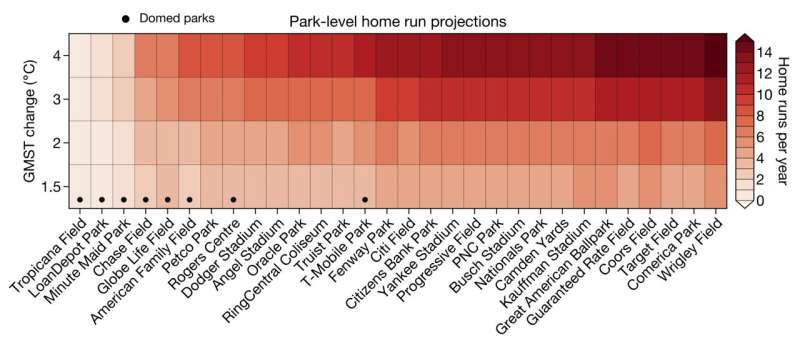

The researchers examined each major league ballpark in the United States to gauge how the average number of home runs per year could rise with each 1-degree Celsius increase in the global average temperature. The actual number of runs per season due to temperature could be higher or lower depending on individual gameday conditions.

They found that the Chicago Cubs’ open-air Wrigley Field—which hosts only a limited number of night games—would experience the largest spike with more than 15 home runs per season, while the Tampa Bay Rays’ domed Tropicana Field would remain level at one home run or less no matter how hot it gets outside. The Boston Red Sox’s iconic Fenway Park and the home of their archrivals the New York Yankees fall in the middle and would experience nearly the same effect as temperatures rise.

Increase in average number of home runs per year for each American major league ballpark with every 1-dgree Celsius increase in global average temperature. © Christopher Callahan

Night games would lessen the influence that temperature and air density have on the distance a ball travels, and covered stadiums such as Tropicana Field would nearly eliminate it, the researchers report. Curbing the rise in home runs—and thus the excitement they bring to a game—might seem counterproductive, but there are additional factors to consider as global temperatures rise, particularly the exposure of players and fans to heat, Mankin said.

“A key question for the organization at large is what’s an acceptable level of heat exposure for everybody and what’s the acceptable cost for maximizing home runs,” Mankin said. “Home runs are one pathway by which temperature is affecting game play, but there are other pathways that are more concerning because they have human risk attached to them.”

The enormous wealth of data available for major league baseball games provided a unique opportunity to identify the repercussions of climate change on a cultural institution, Mankin said. Climate scientists focus on the increased likelihood and severity of natural disasters such as hurricanes, floods, and heat waves because of the far-reaching devastation these events wreak—and because there are records to study them.

“Major League Baseball is a multibillion-dollar industry that is very data-rich, and that privilege allowed us to identify the effect of climate. This critical cultural touchstone for what it means to be American also happens to have a very salient relationship with physics in that temperature actually affects game play,” Mankin said.

“It is really difficult to document how climate change is affecting cultural institutions and forms of recreation generally,” he said. “For most cultural institutions, we simply don’t have the data. In fact, we struggle to track climate impacts around the world because of data poverty. A project like this makes me worry that warming is affecting so many other things we just can’t document.”

The study began with Callahan, an avid baseball fan, wondering about the effect of climate change on baseball and sports in general. “It’s important for us to recognize the potentially pervasive way that climate change has altered, or will alter, all the things we care about that are not necessarily encapsulated in heat waves or megadroughts or category 6 hurricanes,” Callahan said. “The effects of global warming will extend throughout our lives in potentially subtle ways.”

Co-author Jeremy DeSilva, professor and chair of anthropology at Dartmouth, said that evaluating the effect of climate change on cultural institutions can resonate with people’s daily lives more so than large-scale disasters that can appear random and beyond anyone’s control. That can lead to change. Baseball has been a touchpoint for social change in the past, from desegregation to growing corporatization and the outsized influence of money.

“Baseball is one of these ways that American society holds a mirror up to itself and global climate change is just another example—baseball is not immune to it,” DeSilva said.

“This kind of study can be an entry point to understanding a phenomenon that is affecting the planet and every individual on it,” he said. “Maybe people who otherwise wouldn’t have will think about, and have a bigger conversation about, the more impactful and dangerous aspects of climate change once they know how it’s affecting this quintessential game in the history of our country.”

Cultural institutions reflect societal values and baseball encapsulates the American response to climate change, said co-author Nathaniel Dominy, the Charles Hansen Professor of Anthropology at Dartmouth.

“Think about the expression of American cultural values in baseball and how many of them exist in opposition to the other: winning and losing, tradition and change, teamwork and individualism, logic and luck,” he said. “These same tensions are frustrating our collective response to carbon emissions, so it is extremely fitting to explore the effects of climate change on baseball. It is a potent metaphor for the American experience.”

More information:

Christopher W. Callahan et al, Global warming, home runs, and the future of America’s pastime, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (2023). DOI: 10.1175/BAMS-D-22-0235.1

Citation:

Spike in major league home runs tied to climate change (2023, April 7)