Scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) have been monitoring groundwater quality in wells across the country for more than three decades, looking for harmful chemicals or residual substances that may cause harm to ecosystems or humans. In all, they have measured up to 500 chemical constituents, including major ions, metals, pesticides, volatile organic compounds, fertilizers, and radionuclides.

Of these constituents, there have been significant increases of Na and Cl ions and dissolved solids—all related to salinity. Details and trends found in the multidecadal study will be presented at the Geological Society of America’s GSA Connects 2023 meeting on Wednesday, 18 October.

The study is currently part of the National Water Quality Network, continuing work that began in 1992 as part of the National Water Quality Assessment Project. “The original goal was to evaluate the status of water quality in the nation, including groundwater, surface water, and ecological health,” says Bruce Lindsey, a hydrologist with USGS. Over time, they focused on certain constituents that may have lingering detrimental effects.

The researchers sampled wells within three different network types: domestic areas, urban areas, and agricultural areas. Domestic wells, or private wells that are not regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency or a local municipality, represented medium depth aquifers and drinking water. Urban and agricultural wells were shallower, usually around 30 to 50 ft deep.

“The purpose of [sampling] those were to understand the status and trends in the very shallowest water levels,” explains Lindsey. Those shallow wells acted as “sort of a sentinel of what might be moving deeper into the aquifer, so to speak.”

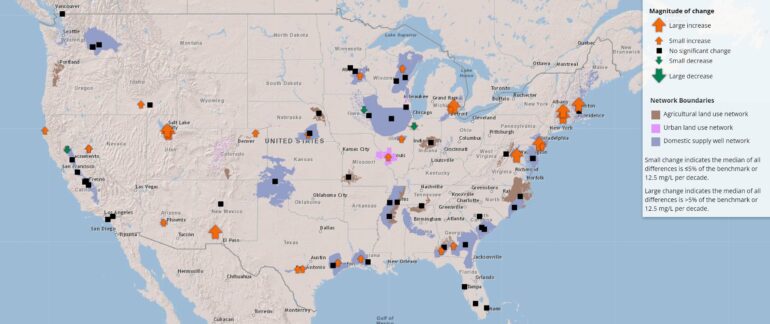

The team identified 82 networks, each with 20 to 30 wells, and identified 28 constituents to track that had levels of concern. Water was sampled every 10 years to track changes in chemical concentrations. These constituents and sampling results can be seen on the USGS’s interactive groundwater map, which shows decadal changes.

“If we look at all 28 constituents across all 82 networks, dissolved solids, chloride, and sodium had statistically significant increases more frequently than any other constituents that we have on our list,” says Lindsey. “If you look at the map, you’ll see patterns right away that jump out.”

One of these spots is the Northeastern and Upper Midwest regions, “particularly around urban areas where there’s cold weather and a lot of road salt,” says Lindsey. “We obtained data on road salt application and found correlations between these increases in chloride and sodium and dissolved solids with the road salt application rates.”

But another region also had elevated levels of Cl, Na, and dissolved solids: the arid regions of the country, especially in the southwest. These regions naturally have high salinity in the soil to begin with, but irrigation complicates the issue.

“When irrigating agriculture in arid regions, you get a lot of evaporation,” Lindsey explains. “So if the salinity of the irrigation water is relatively low, but a large percentage of it evaporates, [salinity levels] can become high.”

These rising levels of Na, Cl, and dissolved solids can cause multiple problems, starting with the environment. Many streams are fed by groundwater, and higher concentrations of chloride in the water can knock out the natural balance that aquatic life is used to. “[Rising levels] is something that can take 20, 30, 40 years to develop … which means that it can also take that long to recover if management of the sources of salinity changes,” says Lindsey.

Dissolved salt ions can also pose problems for infrastructure. As the salinity of groundwater increases, corrosivity can become an issue. Corrosive groundwater, if untreated, can dissolve lead and other metals from pipes and other components present in household plumbing.

Lastly, Lindsey and his colleagues have also discovered a unique issue related to rising salinity with implications for human health. In a sandy aquifer in southern New Jersey, they found that a mixture of low pH water and high salinity groundwater has mobilized the radium— a radioactive element which is harmful to humans.

“It goes back to road salt,” he says. “Road salt is increasing, causing sodium and chloride to increase, which is causing radium to increase.”

Lindsey notes that there seems to be increased awareness of the environmental effects of road salt, with trucks spreading less salt or municipalities switching to a lower-concentration brine. And while dead grass near salted roadways is a clear hint at an oversalting problem, Lindsey hopes that research like this will highlight other cascading impacts of increasing salinity in groundwater.

“The fact that there may be streams that are not able to sustain aquatic life, or that your pipes might start corroding, or this other more rare issue where there’s radium, shows there are other negative aspects [to rising groundwater salinity].”

Their previous research is published in the journal ACS ES&T Water.

More information:

Presentation: gsa.confex.com/gsa/2023AM/meet … app.cgi/Paper/391692

Bruce D. Lindsey et al, Relation between Road-Salt Application and Increasing Radium Concentrations in a Low-pH Aquifer, Southern New Jersey, ACS ES&T Water (2021). DOI: 10.1021/acsestwater.1c00307

Provided by

Geological Society of America

Citation:

US groundwater is getting saltier—what that means for infrastructure, ecosystems, and human health (2023, October 17)