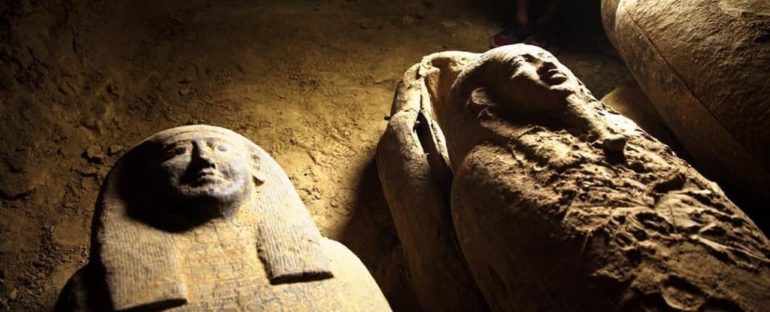

Thousands of years ago, ancient Egyptians were laid to rest in Saqqara, an ancient city of the dead. Priests placed them inside wooden boxes adorned with hieroglyphics, and the sarcophagi were sealed and buried in tombs scattered above and below the sand.

Archaeologists have discovered 160 human coffins at the site over the last three months, which they plan to disperse to museums around Egypt. They even opened a few to examine the mummies inside.

According to experts, some of the Saqqara tombs have colourful curses inscribed on the walls to warn away intruders.

Salima Ikram, an Egyptologist at the American University in Cairo, analysed some animal mummies discovered at Saqqara last year.

She told Business Insider in an email that the inscribed warnings in human tombs mostly serve to deter trespassers intent on desecrating the mummies’ resting places.

A coffin found in Saqqara in September. (Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities)

“They generally state that if the tomb is entered by an impure person (probably in body and/or intention), then may the council of the gods punish the trespasser, and wring his or her neck like that of a goose,” she wrote.

‘Fear of seeing ghosts’

The specific Saqqara curse Ikram quoted was found in the tomb of the vizier Ankhmahor, a pharaoh’s official who lived more than 4,000 years ago, during Egypt’s 6th dynasty. He was buried in a mastaba: an above-ground tomb shaped like a rectangular box. Similar mastabas were built all over Egypt, including near the Giza pyramids.

The curse meant to protect Ankhmahor, roughly translated, warns that anything a trespasser “might do against this, my tomb, the same shall be done to your property.” It also warns of the vizier’s knowledge of secret spells and magic, and threatens to fill “impure” intruders with a “fear of seeing ghosts.”

Curses like that were meant to deter grave robbers, Ikram said.

In the new Netflix documentary “Secrets of the Saqqara Tomb,” she explains that tombs were seen like houses for the dead in their afterlife.

“You wanted to have a fabulous afterlife, so you had a fabulous tomb,” she says in the film, adding that a person’s tomb would be “decorated with all kinds of scenes of the life they wish to enjoy for eternity.”

So trespassers caught trying to steal valuables buried with the dead were punished in a manner commensurate to their crime, Ikram said.

Punishment for violating a noble’s tomb, meanwhile, could consist of beatings, and potentially the removal of a robber’s nose, Ikram added. They would also be required to return the stolen property.

However, the writings on Ankhmahor’s tomb welcome those of pure and peaceful intention, saying that he will protect them in the court of Osiris, Lord of the Egyptian Underworld. Ancient Egyptians believed that Osiris judges dead souls before they pass into the afterlife.

Similar curses appear in a few other tombs across Egypt, Ikram said, “with the majority being recorded from the Old Kingdom” – between 2575 and 2150 BCE.

Not the mummy’s curse from movies

The writings found in tombs like Ankhmahor’s bear little resemblance to the mummy’s curses depicted in horror movies, which often show unwitting archaeologists get killed by the undead after opening burial chambers.

Still, some members of the public weren’t keen to see archaeologists open coffins that had been sealed for more than two millennia.

Who looks at 2020 and says you know what this year needs…a mummy tomb opening? https://t.co/cKUIDILXpj

— Josh Gad (@joshgad) October 5, 2020

But Ikram said there’s little risk of being contaminated with, say, ancient microbes or fungi by handling the mummies.

“If people wear gloves and masks, it should be fine,” she said.

The idea that mummy tombs could contain dangerous pathogens took off in part after archaeologist Howard Carter unearthed King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922.

A member of Carter’s expedition, its financial backer George Herbert died an odd, sudden death six weeks after they opened King Tut’s burial chamber.

So some researchers wondered if the tomb had contained a type of toxic mould that could have infected and killed him. This rekindled talk of a “mummy’s curse,” a concept writer Louisa May Alcott had explored 50 years earlier. But further research showed Herbert died of blood poisoning from an infected mosquito bite on his cheek.

Plus, the walls of King Tut’s tomb were curse-free.

Carter never put any stock in the myth of a mummy’s curse, dismissing it as “tommy rot.” He lived to the age of 64, dying more than 20 years after his fateful discovery.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: