It’s coming. Winds are weakening along the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Heat is building beneath the ocean surface. By July, most forecast models agree that the climate system’s biggest player – El Niño – will return for the first time in nearly four years.

El Niño is one side of the climatic coin called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. It’s the heads to La Niña’s tails.

During El Niño, a swath of ocean stretching 6,000 miles (about 10,000 kilometers) westward off the coast of Ecuador warms for months on end, typically by 2 to 4 degrees Fahrenheit (about 1 to 2 degrees Celsius). A few degrees may not seem like much, but in that part of the world, it’s more than enough to completely reorganize wind, rainfall and temperature patterns all over the planet.

Marine heat waves can trigger coral bleaching.

Alexis Rosenfeld/Getty Images

I’m a climate scientist who studies the oceans. After three years of La Niña, it’s time to start preparing for what El Niño may have in store.

How El Niño affects the planet

No two El Niño events are exactly alike, though we’ve seen enough of them that forecasters have a pretty good idea of what’s likely to happen.

People tend to focus on El Niño’s impact on land, justifiably. The warm water affects air currents that leave areas wetter or drier than usual. It can ramp up storms in some areas, like the southern U.S., while tending to tamp down Atlantic hurricane activity.

How El Niño forms. NOAA.

El Niño can also wreak havoc on the many marine ecosystems that support the world’s fishing industries, including coral reefs and seagrass meadows.

Specifically, El Niño tends to trigger intense and widespread periods of extreme ocean warming known as marine heat waves.

Global ocean temperatures are already at record highs, so El Niño-induced marine heat waves could push many sensitive fisheries to a breaking point.

The problem with marine heat waves

A marine heat wave is just that: a “wave” of extreme heat in the ocean, not dissimilar to an atmospheric heat wave on land.

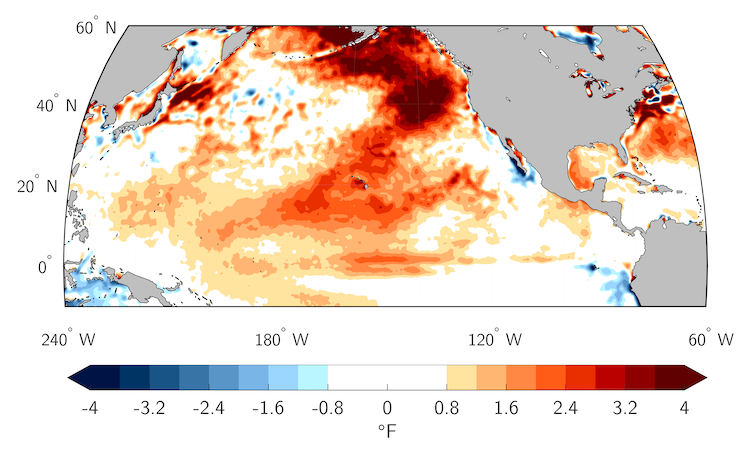

At their smallest, marine heat waves can inundate local bays and coves with hotter-than-normal water for a few days or weeks. At their largest, marine heat waves like the Northeast Pacific Warm Blob of 2013-2014 can grow to gargantuan proportions, with regions three times the size of Texas experiencing ocean temperatures 4 to 6 F (about 2 to 3 C) above average for months or even years.

Fierce marine heat waves like this one in 2019 can wreak havoc on sea life off the North American Pacific Coast with temperatures about 4 to 6 F (2 to 3 C) above normal.

Dillon Amaya

Warm water might not seem like a big deal, especially to surfers hoping to leave their wetsuits at home. But for many marine organisms that are highly adapted to specific water…