Everything in biology ultimately boils down to food and sex. To survive as an individual you need food. To survive as a species you need sex.

Not surprisingly then, the age-old question of why giraffes have long necks has centered around food and sex. After debating this question for the past 150 years, biologists still cannot agree on which of these two factors was the most important in the evolution of the giraffe’s neck. In the past three years, my colleagues and I have been trying to get to the bottom of this question.

Necks for sex

In the 19th century, biologists Charles Darwin and his colleague Jean Baptiste Lamarck both speculated that giraffes’ long necks helped them reach acacia leaves high up in the trees, though they likely weren’t observing actual giraffe behavior when they came up with this theory. Several decades later, when scientists started observing giraffes in Africa, a group of biologists came up with an alternative theory based on sex and reproduction.

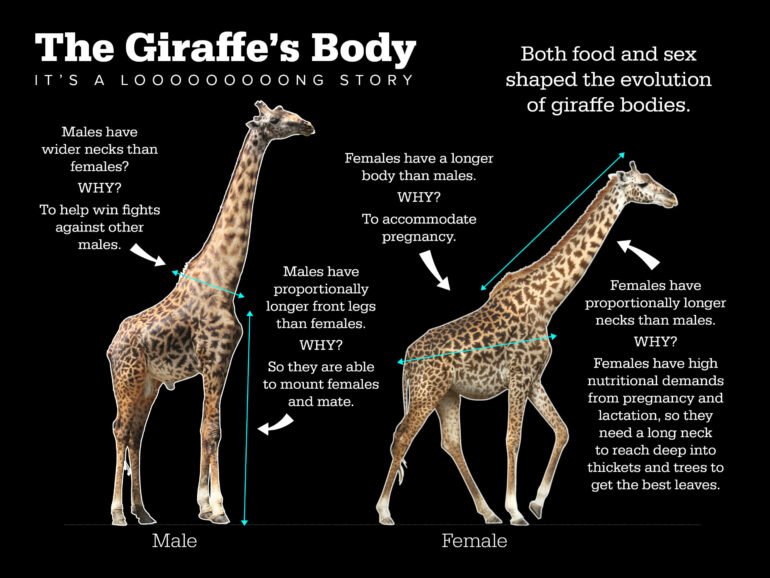

These pioneering giraffe biologists noticed how male giraffes, standing side by side, used their long necks to swing their heads and club each other. The researchers called this behavior “neck-fighting” and guessed that it helped the giraffes prove their dominance over each other and woo mates. Males with the longest necks would win these contests and, in turn, boost their reproductive success. That favorability, the scientists predicted, drove the evolution of long necks.

Since its inception, the necks-for-sex sexual selection hypothesis has overshadowed Darwin’s and Lamarck’s necks-for-food hypothesis.

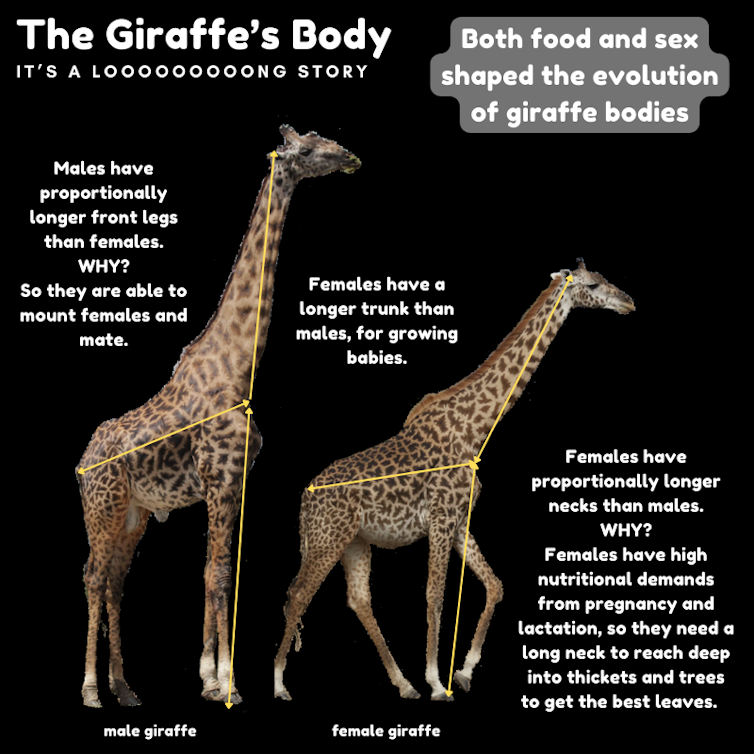

The necks-for-sex hypothesis predicts that males should have longer necks than females, since only males use them to fight, and indeed they do. But adult male giraffes are also about 30% to 50% larger than female giraffes. All of their body components are bigger. So my team wanted to find out if males have proportionally longer necks when accounting for their overall stature, comprised of their head, neck and forelegs.

Necks not for sex?

But it’s not easy to measure giraffe body proportions. For one, their necks grow disproportionately faster during the first six to eight years of their life. And in the wild, you can’t tell exactly how old an individual animal is. To get around these problems, we measured body proportions in captive Masai giraffes in North American zoos. Here, we knew the exact age of the giraffes and could then compare this data with the body proportions of wild giraffes that we knew confidently were older than 8 years.

To our surprise, we found that adult female giraffes have proportionally longer necks than males, which contradicts the necks-for-sex hypothesis. We also found that adult female giraffes have proportionally longer body trunks, while adult males have proportionally longer forelegs and thicker necks.