The last pandemic was bad, but COVID-19 is only one of many infectious diseases that emerged since the turn of this century.

Since 2000, the world has experienced 15 novel Ebola epidemics, the global spread of a 1918-like influenza strain and major outbreaks of three new and unusually deadly coronavirus infections: SARS, MERS and, of course, COVID-19. Every year, researchers discover two or three entirely new pathogens: the viruses, bacteria and microparasites that sicken and kill people.

While some of these discoveries reflect better detection methods, genetic studies confirm that most of these pathogens are indeed new to the human species. Even more troubling, these diseases are appearing at an increasing rate.

Despite the novelty of these particular infections, the primary factors that led to their emergence are quite ancient. Working in the field of anthropology, I have found that these are primarily human factors: the ways we feed ourselves, the ways we live together, and the ways we treat one another. In a forthcoming book, “Emerging Infections: Three Epidemiological Transitions from Prehistory to the Present,” my colleagues and I examine how these same elements have influenced disease dynamics for thousands of years. Twenty-first century technologies have served only to magnify ancient challenges.

Neolithic infections

The first major wave of newly emerging infections occurred with the start of the Neolithic revolution about 12,000 years ago, when people began shifting from foraging to farming as their primary means of subsistence.

Before then, human infections tended to be mild and chronic in nature, manageable burdens of long-term parasites that people carried around from place to place. But full-time agrarian living brought the kinds of acute and virulent infections that we are familiar with today. This global shift was humanity’s first epidemiological transition.

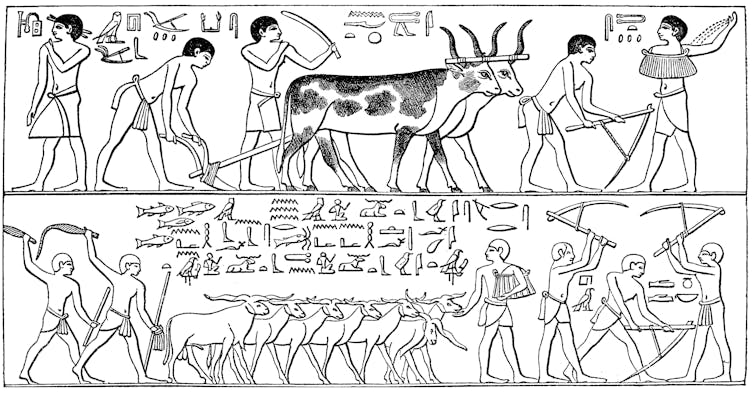

The first emerging infections followed the rise of intensive agriculture.

mikroman6/Moment via Getty Images

Farming itself was not the cause. Rather, it was the major lifestyle changes associated with this new enterprise. Agriculture supplied people with high-calorie grains, but often did so at the expense of dietary diversity, resulting in compromised immunity from nutritional deficiencies.

The human population increased dramatically, and so did the number of large and densely settled communities that could sustain the transmission of deadlier pathogens.

Our ancient ancestors domesticated animals for food and labor, and their proximity to one another created opportunities for livestock diseases to evolve into human diseases.

Finally, the social hierarchies of newly agrarian societies led to disparities in the distribution of essential resources for healthy living.

These challenges of subsistence, settlement and social organization were the root causes of humanity’s first major disease transition.