Gender reveal parties are best known as celebrations involving pink and blue, cake and confetti, and the occasional wildfire. Along with being social media hits, gender reveals are a testament to how society is squeezing children into one of two predetermined gender boxes before they are even born.

These parties are often based on the 18- to 20-week ultrasound, otherwise known as the anatomy scan. This is the point during fetal development when the genitals are typically observed and the word “boy” or “girl” can be secretly written on a piece of paper and placed into an envelope for the planned reveal.

Now there is a new player in the gender reveal game: genetic screening.

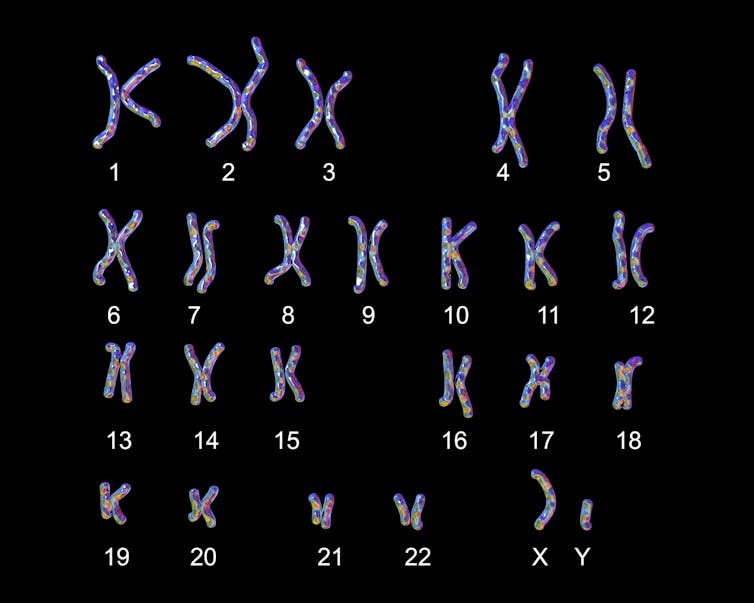

Advancements in genetic research have led to the development of a simple blood test called cell-free DNA prenatal screening that screens for whether a baby has extra or missing pieces of genetic information – chromosomes – as early as 10 weeks into pregnancy. Included in this test are the sex chromosomes, otherwise known as X and Y, that play a role in the development and function of the body.

Prenatal screening tests look for chromosomal abnormalities.

Anastasia Usenko/iStock via Getty Images Plus

This blood test is more informally called noninvasive prenatal testing, or NIPT. Many people refer to it as “the gender test.” But this blood test cannot determine gender.

As genetic counselors and clinical researchers working to improve genetic services for gender-diverse and intersex people, we emphasize the significance of using precise and accurate language when discussing genetic testing. This is critical for providing affirming counseling to any patient seeking pregnancy-related genetic testing and resisting the erasure of transgender and intersex people in health care.

Distinguishing sex and sex chromosomes

Sex and gender are often used interchangeably, but they represent entirely different concepts.

Typically when people think of sex, they think of the categories female or male. Most commonly, sex is assigned by health care providers at birth based on the genitals they observe on the newborn. Sex may also be assigned based on the X and Y chromosomes found on a genetic test. Commonly, people with XX chromosomes are assigned female at birth, and people with XY chromosomes are assigned male. Since cell-free DNA, or cfDNA, prenatal screening can report on sex chromosomes months before birth, babies are receiving sex assignments much sooner than previously possible.

While cfDNA prenatal screening can offer insights into what sex chromosomes an infant may have, sex determination is much more complicated than just X’s and Y’s.

For one, sex chromosomes don’t exactly determine someone’s sex. Other chromosomes, hormone receptors, neural pathways, reproductive organs and environmental factors contribute to sex determination as well, not unlike an orchestra with its ensemble of instruments. Each cello,…