As any avid gardener will tell you, plants with sharp thorns and prickles can leave you looking like you’ve had a run-in with an angry cat. Wouldn’t it be nice to rid plants of their prickles entirely but keep the tasty fruits and beautiful flowers?

I’m a geneticist who, along with my colleagues, recently discovered the gene that accounts for prickliness across a variety of plants, including roses, eggplants and even some species of grasses. Genetically tailored, smooth-stemmed plants may eventually arrive at a garden center near you.

Acceleration of nature

Plants and other organisms evolve naturally over time. When random changes to their DNA, called mutations, enhance survival, they get passed on to offspring. For thousands of years, plant breeders have taken advantage of these variations to create high-yielding crop varieties.

In 1983, the first genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, appeared in agriculture. Golden rice, engineered to combat vitamin A deficiency, and pest-resistant corn are just a couple of examples of how genetic modification has been used to enhance crop plants.

Two recent developments have changed the landscape further. The advent of gene editing using a technique known as CRISPR has made it possible to modify plant traits more easily and quickly. If the genome of an organism were a book, CRISPR-based gene editing is akin to adding or removing a sentence here or there.

This tool, combined with the increasing ease with which scientists can sequence an organism’s complete collection of DNA – or genome – is rapidly accelerating the ability to predictably engineer an organism’s traits.

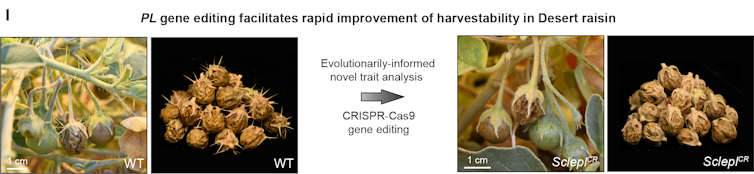

By identifying a key gene that controls prickles in eggplants, our team was able to use gene editing to mutate the same gene in other prickly species, yielding smooth, prickle-free plants. In addition to eggplants, we got rid of prickles in a desert-adapted wild plant species with edible raisin-like fruits.

The desert raisin (Solanum cleistogamum) gets a makeover.

Blaine Fitzgerald, CC BY-SA

We also used a virus to silence the expression of a closely related gene in roses, yielding a rose without thorns.

In natural settings, prickles defend plants against grazing herbivores. But under cultivation, edited plants would be easier to handle – and after harvest, fruit damage would be reduced. It’s worth noting that prickle-free plants still retain other defenses, such as their chemical-laden epidermal hairs called trichomes that deter insect pests.

From glowing petunias to purple tomatoes

Today, DNA modification technologies are no longer confined to large-scale agribusiness – they are becoming available directly to consumers.

One approach is to mutate certain genes, like we did with our prickle-free plants. For example, scientists have created a mild-tasting but nutrient-dense mustard green by inactivating the genes responsible for bitterness. Silencing the genes…