When soaring temperatures, extreme weather and catastrophic wildfires hit the headlines, people start asking for quick fixes to climate change. The U.S. government just announced the first awards from a US$3.5 billion fund for projects that promise to pull carbon dioxide out of the air. Policymakers are also exploring more invasive types of geoengineering − the deliberate, large-scale manipulation of Earth’s natural systems.

The underlying problem has been known for decades: Fossil-fuel vehicles and power plants, deforestation and unsustainable agricultural practices have been putting more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than the Earth’s systems can naturally remove, and that’s heating up the planet.

Geoengineering, theoretically, aims to restore that balance, either by removing excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere or reflecting solar energy away from Earth.

But changing Earth’s complex and interconnected climate system may have unintended consequences. Changes that help one region could harm another, and the effects may not be clear until it’s too late.

Rising temperatures are raising fears that geoengineering may become necessary. Video: NASA.

As a geologist and climate scientist, I believe these consequences are not yet sufficiently understood. Beyond the potential physical repercussions, countries don’t have the legal or social structures in place to manage both its use and the fallout when things go wrong. Similar concerns have been highlighted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the United Nations Environment Programme, the National Academy of Sciences and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, among others.

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy also discussed these concerns in its July 2023 research plan for investigating potential climate interventions.

Risks of solar radiation management

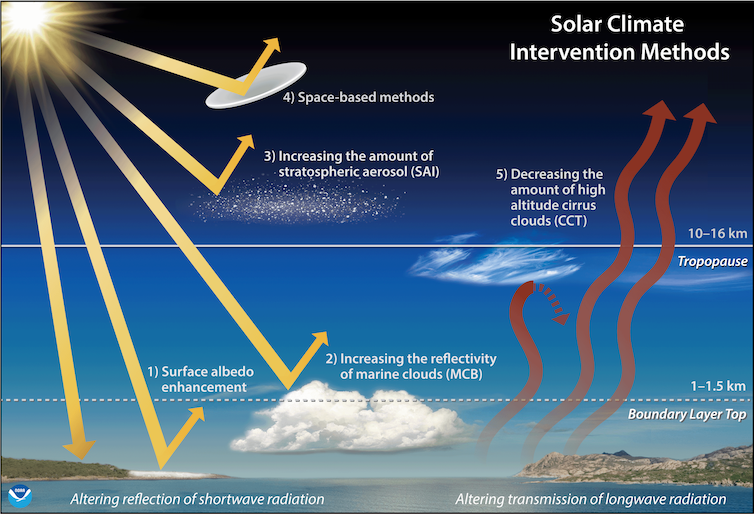

When people hear the word “geoengineering,” they probably picture solar radiation management. These technologies, many of them still theoretical, aim to reflect solar energy away from Earth’s surface.

The idea of stratospheric aerosol injection, for example, is to seed the upper atmosphere with billions of tiny particles that reflect sunlight directly out to space. Cirrus cloud thinning aims to reduce the impact of high-altitude, wispy clouds that trap energy within the atmosphere by making their ice crystals larger, heavier and more likely to precipitate. Another, cloud brightening, aims to increase the prevalence of brighter, lower-level clouds that reflect sunlight, possibly by spraying seawater into the air to increase water vapor concentration.

Some scientists have suggested going further and installing arrays of space mirrors that could reduce global temperature by reflecting solar energy away before it reaches the atmosphere.