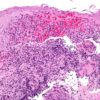

Albert Alexander was dying. World War II was raging, and this police officer of the county of Oxford, England, had developed a severe case of sepsis after a cut on his face became badly infected. His blood was now teeming with deadly bacteria.

According to his physician, Charles Fletcher, Alexander was in tremendous pain, “desperately and pathetically ill.” The bacterial infection was eating him alive: He’d already lost one eye and had oozing abscesses all over his face and in his lungs.

Albert Alexander in uniform.

Courtesy of Linda Willason, CC BY-ND

Since all known treatment options were exhausted and death appeared imminent, Fletcher decided that Alexander was the perfect candidate to try a new, experimental therapy. On Feb. 12, 1941, Alexander became the first known person to be treated with penicillin. Within days he began to make a stunning recovery.

I am a professor of pharmacology, and Alexander’s story is the prelude to my yearly lecture on antibiotics. Like many other microbiology instructors, I’d always told students that Alexander’s septicemia arose after he scratched his cheek on a thorn while pruning rosebushes. This popular account dominates the scientific literature as well as recent articles and books.

The problem is, while descriptions of the miraculous effect of penicillin in this case are accurate, the details of Alexander’s injury were muddled, likely by wartime propaganda.

Breaking the mold

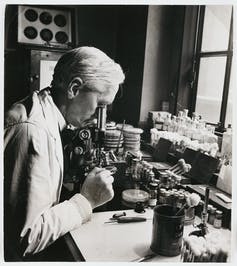

Bacteriologist Alexander Fleming discovered antibiotic penicillin in 1928.

Daily Herald Archive/SSPL via Getty Images

The promise of penicillin as an antibiotic was first noted in 1928, when microbiologist Alexander Fleming noticed something funny in his petri dishes at St. Mary’s Hospital in London. Fleming’s cultures of staphylococcal bacteria did not grow well on plates contaminated with a penicillium mold. Fleming discovered that the mold’s “juice” was lethal to some types of bacteria.

A decade later, a team of scientists led by Howard Florey at Oxford University began the arduous task of purifying the active substance from the “mold juice” and formally testing its antimicrobial properties. In August 1940, Florey and his colleagues published their striking findings that purified penicillin safely wiped out numerous bacterial infections in mice.

Florey then sought Fletcher’s help to try penicillin in a human patient. That patient would be Alexander, whose death seemed inevitable otherwise. As Fletcher stated, “There was all to gain for him in a trial of penicillin and nothing to lose.”

At the time, purified penicillin was extremely scarce, since the mold was slow to grow and yielded precious little of the drug. Despite recycling unprocessed penicillin from Alexander’s urine, there just wasn’t enough available to finish off the infection once and for all. After 10 days of improvement, Alexander…