People around the globe are living longer—but not necessarily healthier—lives, according to Mayo Clinic research. A study of 183 World Health Organization (WHO) member countries found those additional years of life are increasingly fraught with disease. This research by Andre Terzic, M.D., Ph.D., and Armin Garmany documents a widening gap between lifespan and healthspan. Their paper is published in JAMA Network Open.

“The data show that gains in longevity are not matched with equivalent advances in healthy longevity. Growing older often means more years of life burdened with disease,” says Dr. Terzic, senior author. “This research has important practice and policy implications by bringing attention to a growing threat to the quality of longevity and the need to close the healthspan-lifespan gap.”

Dr. Terzic is the Marriott Family Director, Comprehensive Cardiac Regenerative Medicine for the Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Biotherapeutics and Marriott Family Professor of Cardiovascular Research at Mayo Clinic.

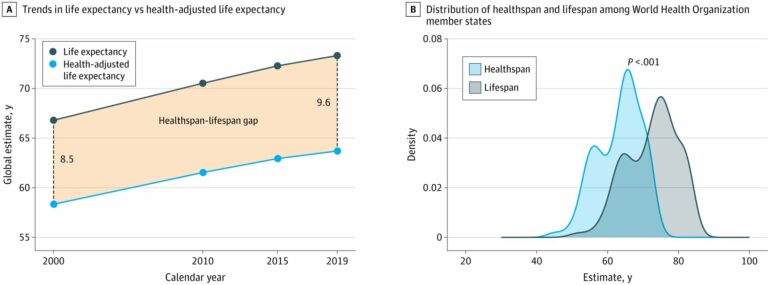

Life expectancy, or lifespan, increased from 79.2 to 80.7 years in women and from 74.1 to 76.3 years in men between 2000 and 2019, according to WHO estimates. Healthspan describes the number of years a person has lived a healthy, active, disease-free life. However, the number of years those people were living in good health did not correspondingly increase. The average global gap in lifespan versus healthspan was 9.6 years in 2019, the last year of available statistics. That represents a 13% increase since 2000.

The U.S. recorded the world’s highest average lifespan-health span divide, with Americans living 12.4 years on average with disability and sickness. This increase from 10.9 years in 2000 comes as the U.S. also reported the highest burden of chronic disease. Mental health, substance use disorders and musculoskeletal conditions were the key contributors to illness nationally.

In addition, the study found a 25% gender disparity worldwide. Across 183 surveyed countries, women experienced a 2.4-year larger gap in lifespan versus healthspan than men. Neurological, musculoskeletal, urinary and genital tract disorders contributed to extended years of poor health among women.

“The widening healthspan-lifespan gap globally points to the need for an accelerated pivot to proactive wellness-centric care systems,” says Armin Garmany, first author and an M.D./Ph.D. student in Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine and Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences. “Identifying contributors to the gap unique to each geography can help inform healthcare interventions specific to each country and region.”

The Mayo Clinic research team studied statistics from the WHO Global Health Observatory. This cross-sectional study provided data on life expectancy, health-adjusted life expectancy, years lived with disease and years of life lost among member states. The healthspan-lifespan gap for each member state was calculated by subtracting health-adjusted life expectancy from life expectancy.

More information:

Armin Garmany et al, Global Healthspan-Lifespan Gaps Among 183 World Health Organization Member States, JAMA Network Open (2024). DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.50241. jamanetwork.com/journals/jaman … /fullarticle/2827753

Citation:

Cross-sectional study shows global divide between longer life and good health (2024, December 11)