Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to [email protected].

How does soap clean our bodies? – Charlie H., age 8, Stamford, Connecticut

Thousands of years ago, our ancestors discovered something that would clean their bodies and clothes. As the story goes, fat from someone’s meal fell into the leftover ashes of a fire. They were astonished to discover that the blending of fat and ashes formed a material that cleaned things. At the time, it must have seemed like magic.

That’s the legend, anyway. However it happened, the discovery of soap dates back approximately 5,000 years, to the ancient city of Babylon in what was southern Mesopotamia – today, the country of Iraq.

As the centuries passed, people around the world began to use soap to clean the things that got dirty. During the 1600s, soap was a common item in the American colonies, often made at home. In 1791, Nicholas Leblanc, a French chemist, patented the first soapmaking process. Today, the world spends about US$50 billion every year on bath, kitchen and laundry soap.

But although billions of people use soap every day, most of us don’t know how it works. As a professor of chemistry, I can explain the science of soap – and why you should listen to your mom when she tells you to wash up.

You’ll be amazed at how much work it takes to make a bar of soap.

The chemistry of clean

Water – scientific name: dihydrogen monoxide – is composed of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. That molecule is required for all life on our planet.

Chemists categorize other molecules that are attracted to water as hydrophilic, which means water-loving. Hydrophilic molecules can dissolve in water.

So if you were to wash your hands under a running faucet without using soap, you’d probably get rid of lots of whatever hydrophilic bits are stuck to your skin.

But there is another category of molecules that chemists call hydrophobic, which means water-fearing. Hydrophobic molecules do not dissolve in water.

Oil is an example of something that’s hydrophobic. You probably know from experience that oil and water just don’t mix. Picture shaking up a jar of vinaigrette salad dressing – the oil and the other watery ingredients never stay mixed.

So just swishing your hands through water isn’t going to get rid of water-fearing molecules such as oil or grease.

Here’s where soap comes in to save the day.

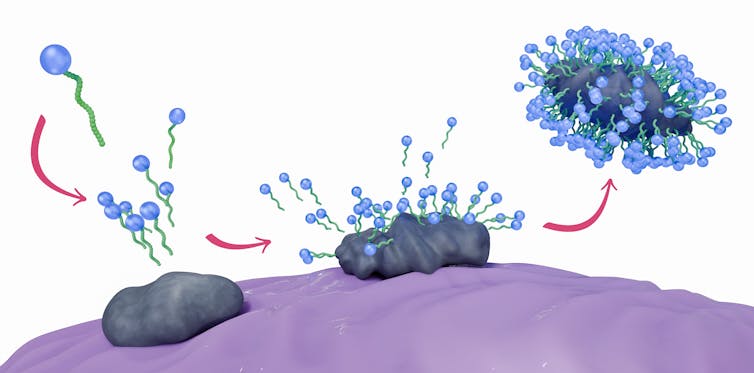

Soap, a complex molecule, is both water-loving and water-fearing. Shaped like a tadpole, the soap molecule has a round head and long tail; the head is hydrophilic, and the tail is hydrophobic. This quality is one of the reasons soap is slippery.

It’s also what gives soap its cleaning superpower.