When most people hear about electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT, it typically conjures terrifying images of cruel, outdated and pseudo-medical procedures. Formerly known as electroshock therapy, this perception of ECT as dangerous and ineffective has been reinforced in pop culture for decades – think the 1962 novel-turned-Oscar-winning film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” where an unruly patient is subjected to ECT as punishment by a tyrannical nurse.

Despite this stigma, ECT is a highly effective treatment for depression – up to 80% of patients experience at least a 50% reduction in symptom severity. For one of the most disabling illnesses around the world, I think it’s surprising that ECT is rarely used to treat depression.

Contributing to the stigma around ECT, psychiatrists still don’t know exactly how it heals a depressed person’s brain. ECT involves using highly controlled doses of electricity to induce a brief seizure under anesthesia. Often, the best description you’ll hear from a physician on why that brief seizure can alleviate depression symptoms is that ECT “resets” the brain – an answer that can be fuzzy and unsettling to some.

As a data-obsessed neuroscientist, I was also dissatisfied with this explanation. In our newly published research, my colleagues and I in the lab of Bradley Voytek at UC San Diego discovered that ECT might work by resetting the brain’s electrical background noise.

Despite its high effectiveness in alleviating depression symptoms, misperceptions about ECT made it unpopular.

Listening to brain waves

To study how ECT treats depression, my team and I used a device called an electroencephalogram, or EEG. It measures the brain’s electrical activity – or brain waves – via electrodes placed on the scalp. You can think of brain waves as music played by an orchestra. Orchestral music is the sum of many instruments together, much like EEG readings are the sum of the electrical activity of millions of brain cells.

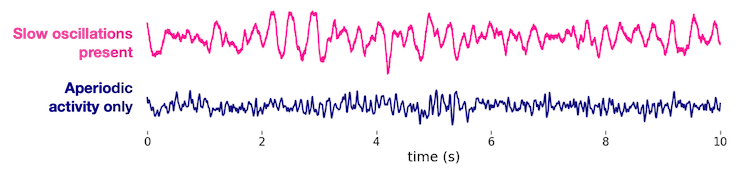

Two types of electrical activity make up brain waves. The first, oscillations, are like the highly synchronized, melodic music you might hear in a symphony. The second, aperiodic activity, is more like the asynchronous noise you hear as musicians tune their instruments. These two types of activities coexist in the brain, together creating the electrical waves an EEG records.

Importantly, tuning noises and symphonic music shouldn’t be mistaken for one another. They clearly come from different processes and serve different purposes. The brain is similar in this way – aperiodic activity and oscillations are different because the biology driving them is distinct.